“SWORD OF THE PIG,” (1983). LACQUER ON WOOD; CHARCOAL, GRAPHITE, AND INK ON PAPER; PLEXIGLASS; SILKSCREEN ON ALUMINUM. 97 3/4 X 229 1/2 X 28 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

“UNTITLED (JULES),” FROM THE “MEN IN THE CITIES” SERIES, (1981). GRAPHITE, CHARCOAL, AND DYE ON PAPER. 96 X 60 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

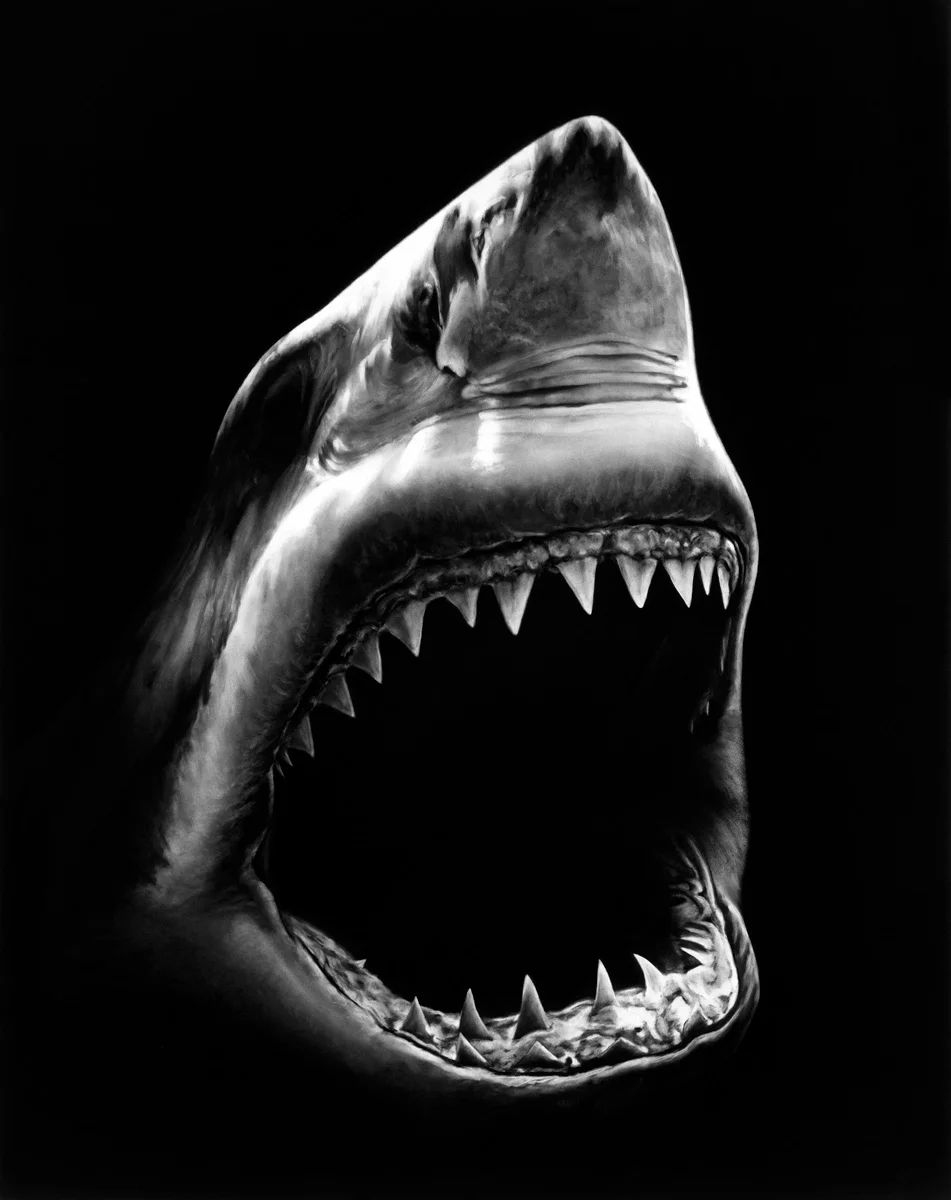

“UNTITLED (SHARK 5),” (2008). CHARCOAL ON MOUNTED PAPER. 88 X 70 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

“UNTITLED (HERCULES),” (2008). CHARCOAL ON MOUNTED PAPER. 96 X 70 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

“UNTITLED (CROWN OF THORNS),” (2012). CHARCOAL ON MOUNTED PAPER. 70 X 88 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

“UNTITLED (BIRD HEAD),” (2011). CHARCOAL ON MOUNTED PAPER. 70 X 120 INCHES. COURTESY THE ARTIST.

STUDIO VIEW

STUDIO VIEW

STUDIO VIEW

[](#)[](#)

Robert Longo

The Road To Enlightenment Is Gridlocked

Robert Longo achieved extraordinary success in the art world early in life, conquering New York City in the late ’70s and early ’80s along with other such _enfants terribles_ as David Salle, Julian Schnabel, and Cindy Sherman. They were Baby Boomers, raised in an era of unparalleled prosperity tempered by equally extreme paranoia. Longo and his colleagues were among the first generation of artists to grow up consuming pop culture as we know it, absorbing images, music, and concepts in a way that caused them to question the purpose of art. Longo was trained as a sculptor but favored drawing as his preferred medium to explore the concepts of power and status with vivid, aggressive charcoal sketches. His series “Men in the Cities”—dozens of drawings produced between 1979 and 1982—is still considered his seminal work. In the drawings, neatly dressed men and women are lurching forward, writhing in agony (or is it ecstasy?), appearing to collapse from an unseen gunshot or incapacitated by psychedelics at a Dead concert. By the mid-80s he was successful, famous, and ready to venture into other areas of artistic expression. “My way of being avant-garde is to make a movie and have 30 million people think I’m avant-garde, not just a bunch at some arty cocktail party,” he said in a _New York Times_ interview from 1985. Mass media fascinated him in its ability to reach out and touch people who would never have had access to his art exhibits. He began directing music videos for New Order, Megadeth, and R.E.M. with marked success, and took his directing ambitions to the big screen with the Keanu Reeves cyberpunk thriller _Johnny Mnemonic_ (1995). This Spring, Longo is exhibiting “Strike The Sun”—a seven-picture study of the U.S. Capitol building—in New York with Petzel Gallery as well as with his longtime distributor Metro Pictures.

_You’re known for producing drawings that are deeply evocative of sculpture, in that they seem often three-dimensional and work heavily with concepts of light and dark. Was that a conscious decision on your part or did it evolve naturally? Could you ever imagine reversing that concept (i.e., creating sculptures that seem flat and two-dimensional)?_ My degree is in sculpture. I am a pretty physical person. I’ve always drawn; it’s the basis of everything. When I moved to N.Y.C. I was broke and found some backdrop paper in the trash—big sheets—and

I began drawing. It gave me the chance to work in the scale I wanted. My first real seminal works in 1976 were actually sculptural reliefs made out of cast aluminum painted with enamel and car paint. I have continued to work with sculpture throughout my career. These last 10 - 12 years I’ve focused on charcoal drawings. The way I do these charcoal drawings is similar to the sculptural process; I feel that

I am carving out the images.

_What is your current relationship to the “Men in the Cities” series? How has your perspective on that work changed over the last 35 years?_ That series was my launch pad. Their success was so powerful that it entombed me in some way. I’ve spent a great deal of my career running away from that body of work. I think if you succeed in creating an archetypal image that enters the visual landscape, what happens is you eventually lose authorship of it. It infuses itself into the culture. Now I am quite proud of the work, but it was a long time ago.

_The abovementioned series is strongly associated with a time and place; for many, it was the Wall Street boom of the 1980s. Wall Street and its privileges are still very much on the minds of news media and popular culture. What would “Men in the Cities” look like if it was created today? Would it be any different?_ This is actually a perfect example of how you end up losing authorship over these things. The people I depicted in those early works were never meant to reflect Wall Street, they were people I knew, primarily from the downtown punk and no wave art and music scene, they were my band mates, they were my artist friends—the community I was hanging out with. The irony is that somehow these doomed, white men and women became associated with yuppies and Wall Street. What I tried to do was create an image with a uniform; women wore dresses and skirts, men wore shirts and ties, but they were just urbanites, city dwellers.

_The theme of this issue is games. Many would argue the fine art world is ripe with gameplay. Would you agree? How so?_ Just as much as life is a narrative, a game, with a beginning, middle, and end. Games make life easier to understand; someone wins, someone loses. It’s clear—unlike real life—like the difference between the front page of the newspaper to its back page with the sports scores. Unfortunately as an American, we’re raised with extreme competitiveness to win. I grew up as a football player and I come from the tribe of sports, so I do have a competitive edge, which I try to constantly keep in check. I try not to think about the games that go on in the art world. I just make the stuff. It’s all tragically disappointing to me that as artists we are trying to deal with the pursuit of truth and then there’s this dark forest of the “art world” to deal with.

_Any sort of game you enjoyed as a child that you’ve continued to play as an adult, in spirit?_ I am a big sports fan. I have season tickets for the Knicks, I love the New York Giants, and \[I’m\] a big Yankees fan. I played basketball for many years until recently I had a stroke and had to stop. Sports are a really big part of my life. There was one game called Who Can Fall Dead Best that I played as a kid. This was actually a huge influence on my early work and the \[“Men in the Cities”\]. The idea was that one kid would have a “gun” and the other kids would all run away, and the one kid would pretend to shoot us, and whoever fell dead the best would get to shoot next. We were mimicking the movies and this culture of violence in imagery that was just beginning to emerge in mass media.

_Many of your series, including “Monsters,” “Beginning of the World,” and “Perfect Monsters,” deal with the themes of power and helplessness. Does creating art make you powerful? What, contrarily, is disempowering about your relationship to art?_ I believe an artist is a kind of reporter—\[the artist\] reports what it’s like to be alive in his or her time by reflecting this in the images one makes—\[looking\] at history. I choose images that are both socially relevant and intensely personal. I turn a dramatic moment or image into a highly charged constructed picture that can consume the viewer over and over again. It makes an image last an eternity. _Some people have criticized you for your association with mass media_—_movies, music, T.V. What did/do you make of that criticism, and do you care? What does mass media offer you that the traditional “fine arts” do not?_ I’ve been pretty banged up by the press and media—but I’m still standing. I am a warrior. I am very happy being an artist. Other media have too many strings attached.

_This issue houses spring fashion collections. Do you have any perspective on your appeal to the fashion world? How so?_ Not really. Of course I’m flattered by it. I know very little about fashion trends but I clearly know what I like, most of which is the work of friends, like Narciso Rodriguez, Rick Owens, and Proenza Schouler.