He stands curiously but stoically, teetering forward at a slight bend, staring out over the diving board into a presumably rarely used and crystalline pool. The palm trees sway in surround, their perfectly-planted foundations side-flanked by jacarandas and a lone oak. He swivels and paces the length of the diving board away from the water, deliberate and melodic, as if he’s toeing to a beat in his head, then swivels and repeats. Is he gonna plunge? Well, sort of.

Tahar Rahim is at the Consulate General of France in Beverly Hills promoting A Prophet, a prison drama whereby his quiet and head-tucked character becomes a conflicted kingpin for the Corsican mob.The film has just won nine César awards, and will catalyze the fledgling actor’s ascent as one of the more transformative and committed actors in contemporary French cinema.

This is over a decade ago. While I do meet Rahim, I am in fact on site to interview legendary Jacques Audiard, director of A Prophet. “Did you meet Tahar?” he asks, as we sit down for coffee with his co-writer, Thomas Bidegain, who nods in agreement, “He’s going to be very special.”

Time flies and it crawls, as we’re acutely aware in 2020. It flies when you’re bouncing around Thailand, as Rahim has recently done for his lead role in the BBC/Netflix series,The Serpent, a slick story of the serial killer, Charles Sobhraj, who is known to have murdered in grisly fashion at least ten young backpackers in Southeast Asia during the 1970s. Conversely, time crawls when you’re not allowed to leave your home save for sanctioned groceries, when you haven’t seen friends or family for nearing a year, when the exciting The Serpent location converts to an unremarkable village in rural England. It flies and it crawls.

“Nah, come on,” says Rahim with an eye roll when I cite the “imprisonment” people have expressed feeling in the course this year’s flying and crawling time, in the throes of Covid-19 lockdowns, quarantine, and non-stop news feeds contextualizing the former. “When people use this expression, I mean, I understand it’s coming from a habituated situation, and a comfortable one, and you are in a way ‘in prison’ from what you’re used to doing… But you still have freedom, and I’m in real jail. It’s a whole different thing.”

But we’re not talking about Covid-19, if you can imagine. We’re talking about the human rights stain on American history (and still partially functioning detainment facility) that is Guantánamo Bay. Rahim stars in upcoming drama, The Mauritanian, out in February, as Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a North African with a transient and tenuous affiliation with Al-Qaeda, hastily renounced after its inception, who is imprisoned under presumptive orchestration of 9/11 recruitment, among other crimes. Slahi was never issued a charge, though, during his fourteen years inside the notorious torture complex.

In the film, Jodie Foster and Benedict Cumberbatch play contending lawyers—exceptionally I might add—both of whom, in stylized simultaneity, struggle under the weight of the realizations that the US government is decisively and criminally persecuting presumed terrorists on a very need-to-know, documented though heavily scrubbed, basis. Slahi, in 2005, penned a memoir, Guantánamo Diary, the basis for the film that, following its declassification in 2012, published and translated worldwide in 2015. Slahi did not receive a copy in prison, where he stayed until his release in 2016.

Not TV jail. No cable, no lovers appearing through thick glass to catch you up on the kids, no exercise yard, no due process. Something else entirely. And while Rahim will attest “it felt so good to just be in an airport”, in the context of his recent and short-lived travel—first, a quick family trip to Morocco prior to the second lockdown in France, because he “knew it was coming”, and second, for the aforementioned completion of The Serpent in nowhere UK—we’re talking about an imprisonment truly inaccessible by our current experience.

“The preparation started, like every part that I pick…,” but he trails off, not completing the thought, and it’s evident here that there is no consistency for Rahim’s preparation—how can there be when the absorption is so individuated? This particular role threw him for something of a loop. “My first reaction, at the time,” he says with a wrinkled brow of skepticism, “was sort of a disappointment, because I judged the movie from its title [originally: My Time in Guantánamo]. I’ve been offered many parts in America that were stereotypical, and that was my first thought.”

The film does tend to stereotype—the stylized, swirling sand and the prayers to Allah and the violence—and then you realize you’re wrong, that’s not what’s happening. What’s happening is a sort of reversal, a worming through of the irrational fear and villain-making of the Middle East in recent decades, the reason the film’s imaging feels “stylized” to begin with. Instead, at the core of The Mauritanian—and this filters through nearly every key character—is morality’s conscience, whatever side of justice it’s on, and ultimately, forgiveness. “And when I read it,” Rahim continues, “I cried twice. And… and I’ve discovered that horrible story. We know a lot about Guantánamo. We know what happened. So it’s not a secret. But most importantly, it’s about this man. And the way he got through this with such humanity, such humor, and the way he took over what would have happened to a normal person… because it’s not normal to go through this, to come out wiser than before and holding no grudge with anyone. I mean, it’s incredible.”

The source material, of course, is rich. In the film, Slahi is begged, in the face of mounting torture and a long road ahead of legal side-stepping and obstructions, by the pained yet achingly steadfast attorney, Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster), to “write it down”. And what yields is frankly sickening. You watch Slahi be gagged and beaten. The colors blur with his vision and the sound design nauseates. You watch him be shackled in front of 500 watt speakers while heavy metal blasts for hours. You watch him be straddled by an appointed humiliator in BDSM gear, who attempts to destroy every fiber of his sexually constructive conscience. And punches, and kicks, and racist foaming at the mouth. You watch it because it was written. This is real. “I remember the first time I talked to him,” recounts Rahim of meeting Slahi, “I got so impressed by his smile, his sense of humor, his nature. Totally heartfelt. I was like, ‘How’s that possible?’ You know? If it wasn’t real, I couldn’t believe it. We talked about everything. And I didn’t want to, I didn’t want to dig too much in those hard memories. I didn’t want to bother him or embarrass him with those awful memories. Plus, I had the book. I had some recordings from him that Kevin [Macdonald, director] sent to me. From then on, I knew the guy and I wanted to catch a soul, which is way more to me, as he is not a famous person—he is not a celebrity. I can mimic him but not too much. So I wanted to catch his soul, his spine, in a way.”

This feels a romantically French step further than your routine character manifestation. His spine. In the film, Rahim’s spine gradually shapes into a capital letter ‘C’, as his gait, his spirit, and rationale are incessantly wrung by the hands of uniformed men and women. “I got into the cell,” he shares on first visiting the set in South Africa, “like a very small cell, and reading about it is something… but experiencing it is something different, totally different. I laid down on the bed, looked at the roof, and all around me. And it’s like a tiny box. There’s only one light, no windows, just a little toilet. Not even a mirror. And it’s very small. The light is all green, and it’s on 24/7.”

We see this a lot of course. This green, tiny box. It looks fucking cold, and it looks fucking harsh. And in several instances, where Slahi has created here something of a familiarity—be it with an unseen prison mate and lifeline next door, or with his pens and pad atop a makeshift mattress desk—it’s hurriedly dismantled, violently sent spilling to the floor, or sent somewhere we’ll never really know… even the home made in this green box is transient and subject to pulverization. Rahim notes that he insisted on experiencing real shackles instead of fake ones, which left bruises for the entirety of filming after just one day of wear. He describes the challenging leaps in language from his native Algerian to Arabic, and his expressing Slahi’s self-taught English in a sort of pyramid shape through the arc of the film—as something of a cotton ball in his mouth thins and dissolves to achieve annunciation despite the horrific treatment.

The treatment of prisoners like animals cuts a certain silhouette, of course. “And then I did a drastic diet to lose weight,” Rahim continues. “I tried to isolate my mind from my body. It’s impossible to completely isolate, self-isolate… and not talk to people while prepping a movie. So it’s impossible. But inside of me, I was trying to separate—isolate my mind and let it, you know, find some truth. But when you get on such a drastic diet, you reach a point where the emotions, you don’t even control them. They pop out. And then trusting my guts to lead me to what I feel could be truthful.”

Truthful is that this is one of those “beyond the limits” stories. We know these. Stories of uncanny perseverance and strength. This person lifts a truck while their screaming infant is wedged beneath its squealing tire. This person lives on semi-poisonous berries in the Wyoming wilderness for ten days. This person takes three bullets to the stomach while charging an assailant, and lives to collect the medal and pop a Christmas photo with no obvious changes. Still, who the hell are these people? I ask Rahim if the resilience demonstrated in Slahi is buried within all of us. He considers, then declares resolutely, “No, I don’t think so…” Then he rethinks the question, “I think we all have this inside of us in a way. How can I put it? It can be revealed when you have to go through an extreme situation. And that can help you, but it has to be fed by something else. For example, this is faith, or the faith in the rule of law—the facts specifically about him, the fact that he is innocent. How can you go through 70 days of torture if you’re not innocent? But I think that every human being has this inside of themselves.”

Conversely, might it be ascertained, then, that every human has inside of them the ability to torture? The Serpent’s Charles Sobhraj, who earned his nickname after repeatedly slithering from the claws of the law, is a candidate to consider—an arguably glamorized and pedestaled candidate whom The Guardian just reminded us, during a profile of Rahim, that “as recently as 2014, GQ magazine ran a splashy interview with this ‘funny, enigmatic, absurd and engaging’ psychopath”. Rahim, however, had no desire to meet Sobhraj, regardless how romantically alluring a Nepalese prison visit might have sounded. Why? Because of basic decency. “Nobody should do this,” Rahim remarks of torture, “no government, no kingdom, no one. And plus, this is our democracy. We’re not supposed to do this and it’s completely inhumane. I mean everybody has to be judged for what they did whether you’re innocent or guilty but being tortured? C’mon, we’re not animals, it’s awful.”

Earlier, when discussing the extraordinary physical duress that Slahi suffered, Rahim speaks of the depths of depletion to survive: “It’s instinctive, it’s animal.” On the flip side, he tells The Guardian he saw Sobhraj “as an animal” in order to assume the icy galant and cold-blooded remorselessness exhibited by the killer in the media, court filings, and so forth.

We’re onto something here. Fundamentally, in just these two stories, we’ve animal ends demonstrated on opposite points of the behavioral spectrum. And it would seem Rahim is seeking to fill that vast pocket in-between, where we as viewers, spectators, or readers can’t fathom the far reaches… but can perhaps understand our species’ capability of going there.

To that end, Rahim affirms that the depths of his preparation for Slahi equipped him with a new sensibility for accomplishing filmic extremes. “Sometimes it’s very hard for an actor to reach their emotions,” he shares. “It’s strange when you’re here laughing with your friends and then you gotta be in front of the camera, and pretend you’re so sad that you have to cry or go crazy—it’s tough sometimes. In this particular case, I remember fasting led me to a range of emotions that I never experienced before. At some point, it can be hard for you to memorize things because you don’t have enough energy or vitamins, but emotionally it leads you somewhere. You don’t go and pull your emotions—it’s the other way around. And so if one day I have to play a really emotional scene… I’ll just fast, I’ll just starve for two days.”

We’re of course in the business of entertainment. Nonetheless, moments like these—fasting for role preparation, portraying people who do sick things to others—tend to ask: what’s the point of all this? Rahim has leaned toward artsier French films over the last decade, because, as he alluded to earlier, most roles, not shockingly, offered from the US tended to be those of stereotypes (though he did dip his toes into the terrorism theme for an English speaking role as an FBI agent in Hulu’s 10-installment series, The Looming Tower, in 2018). Surely he enjoys what he’s doing, cherishes the process, and feels blessed. But the sum is greater than its parts, right? I ask about the ability of cinema to influence people’s awareness around real issues. Perhaps in the modern news age and digitized everything, it takes a stylized, punching capsule like The Mauritanian to really jar people’s sensibilities? “Of course cinema has that power,” he says assuredly, though with a measure of caution at sounding hyperbolic. “I’m not saying cinema is made to do this, but when you have that power, it’s a popular art, it’s the easiest way to talk to people. Yes, cinema can do this when it’s made with faith and justice and when you’re truthful. It can be stronger than a documentary sometimes.”

Rahim is a father of two with French actor, Leïla Bekhti, whom he met on set of A Prophet (that scenario is non-biased beyond the reaches of Hollywood it would seem!), and you can imagine he’s a pretty good one. What informs these reads of contemporary men? Well, a lot of things I suppose, but I’d venture to say the most percolating is a gentle, mischievous demeanor, one you can envision consistently engaged, wrestling or crafting or cooking up all sorts of wondrous imaginings late at night that lend to sound sleep as opposed to something else. And while his CV boasts of realism, Hollywood is yet to see a family-focused manifestation of him on screen, or a role as something of an everyman (Judas opposite Joaquin Phoenix’s Jesus Christ in 2018’s Mary Magdeline doesn’t quite cut the mustard). This was soundly present in France’s Our Children—in the company of a remarkable Émilie Dequenne—though again a pivot point is the meshing of traditional French roots with the geo-ethnic mix that defines so much of the complex contemporary national identity.

How do we get beyond the political? We know that most often the US machine would sooner spawn a superhero film or redo something that once filled seats (albeit with three times the budget), but perhaps the upending of the world’s health concern, the institutional implosion we’ve seen with the latest civil rights movement, which rippled abroad, will germinate a desire for more genuine, character-driven content. Where the white guys aren’t the only ones playing the lawyers, and Rahim isn’t stuck driving a taxi cab. He takes polite issue with my example, though, and perhaps illumines my own problematic American wiring of perception that we are what we do, we are where we come from.

Instead, he says, it’s in the writing, and it includes anyone who touches the process of making a film. “I think we need to tell stories about characters, and not only, for example, whether you’re Black or White or Arabic or Asian. Usually there’s influence that leads a story and an environment to something more political that finally narrows the possibilities of telling stories. For example, in France when I have to answer that question, I usually say ‘Oh, you want to tell the story of a North African or French-African guy—just try not to always focus on where they’re from, why they’re here, the social problems, the political problems.’ Nowadays, in our society you can find Black, White, Arabs, people from all over the world in different jobs, in different positions in every structure. If you tell the story of this guy, for example, like you said, ‘the taxi driver’—it could be everybody, as long as it’s believable… why not? We have lawyers from every ethnicity, bosses, cops, criminals as well, and it might be a good direction to start with.”

It’s not what, it’s who. In retrospect, there was an identity reflected back in that Beverly Hills pool that winter afternoon a decade ago, and it probably read to Rahim as undulating as the palm fronds draping the austere back yard. And while an industry, and a planet, may have a long ways to go, it could also be said, at this perverse moment in time, they have a lot to look forward to. From his locked down home in Paris, where he leans into an iPhone as if it’s a source of heat, the laugh lines making frequent appearances, and the hands of an artist continually helping to sculpt his thoughts, one would like to come banging on the door when this is over—because it’s always a small celebration when this is over— and treat him to an apero of Pastis, out amongst the sunsetting city.

That will have to wait, of course, but I do propose ending the interview with optimism. I ask the actor what he’s most looking forward to when the world is back to organizing sporting events for 80,000 screaming ticket holders wont to hug and slap high-fives when the favored on the pitch wins favor, back to pinging 175,000 flights a day from hub to hub around the planet, or popping by your new neighbors for some English breakfast and biscuits. Rahim smiles wide at the prospect, almost not sure where to begin, but then boils it down quite simply. “Truly,” he says, “I came to realize that what I miss the most is coffee and cigarettes on a beautiful terrace every morning. I miss it, and I wish I could just start my day like this. I never realized how important it was for me because it’s my moment: I sit down, take my coffee, and light a cigarette, think a little, give some calls, and then start my day. But yeah, I would go for this first, and then I would go for a movie, and then I would call my friends and say, ‘Let’s have a party guys.’”

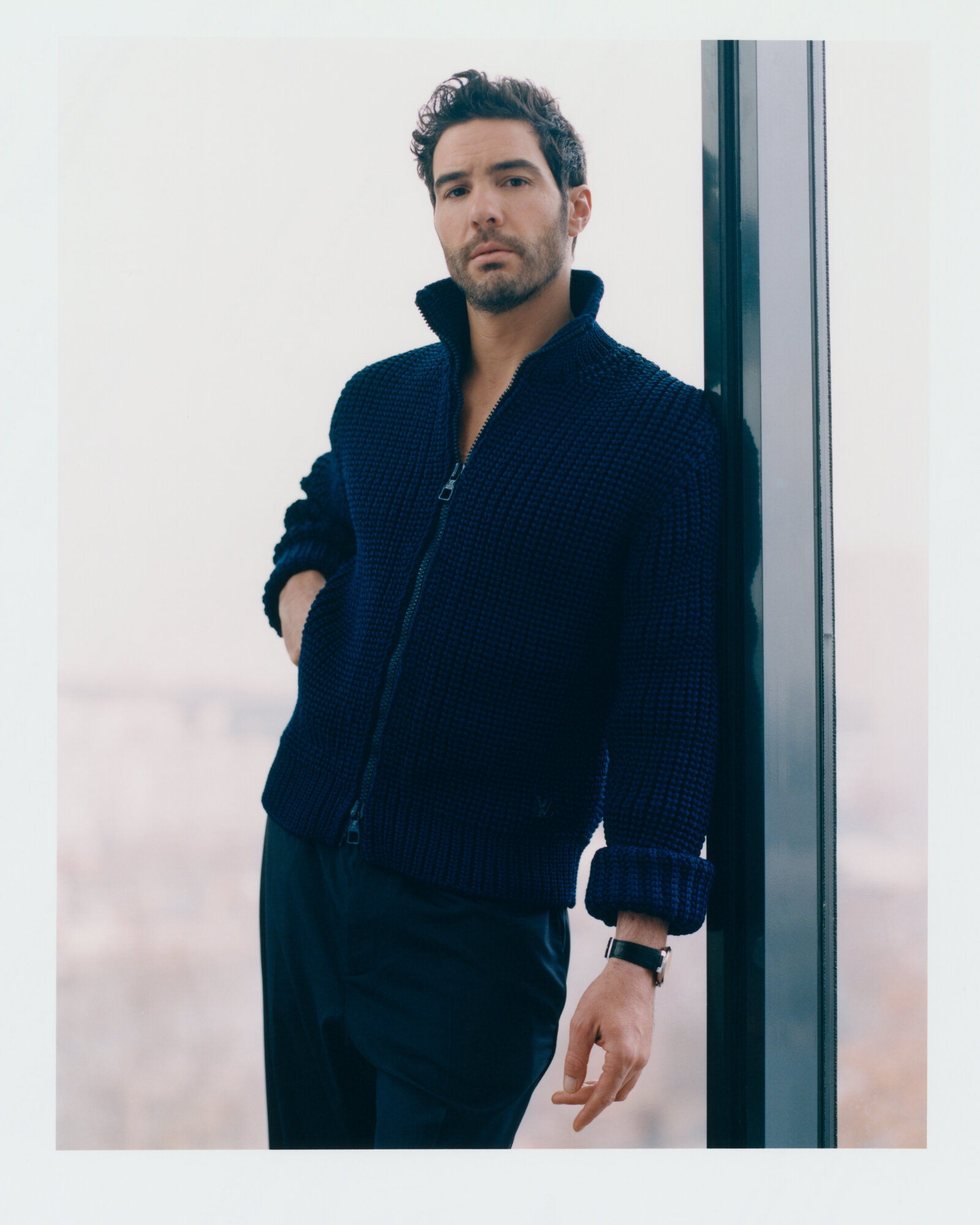

Photographer: James Weston

Stylist: Nicolas Klam

Hair: Nabil Harlow at Calliste Agency

Makeup: Anne Bochon

Styling Assistant: Augustin Puzio

Location: Pullman Paris Centre Bercy Hotel

He stands curiously but stoically, teetering forward at a slight bend, staring out over the diving board into a presumably rarely used and crystalline pool. The palm trees sway in surround, their perfectly-planted foundations side-flanked by jacarandas and a lone oak. He swivels and paces the length of the diving board away from the water, deliberate and melodic, as if he’s toeing to a beat in his head, then swivels and repeats. Is he gonna plunge? Well, sort of.

Tahar Rahim is at the Consulate General of France in Beverly Hills promoting A Prophet, a prison drama whereby his quiet and head-tucked character becomes a conflicted kingpin for the Corsican mob.The film has just won nine César awards, and will catalyze the fledgling actor’s ascent as one of the more transformative and committed actors in contemporary French cinema.

This is over a decade ago. While I do meet Rahim, I am in fact on site to interview legendary Jacques Audiard, director of A Prophet. “Did you meet Tahar?” he asks, as we sit down for coffee with his co-writer, Thomas Bidegain, who nods in agreement, “He’s going to be very special.”

Time flies and it crawls, as we’re acutely aware in 2020. It flies when you’re bouncing around Thailand, as Rahim has recently done for his lead role in the BBC/Netflix series,The Serpent, a slick story of the serial killer, Charles Sobhraj, who is known to have murdered in grisly fashion at least ten young backpackers in Southeast Asia during the 1970s. Conversely, time crawls when you’re not allowed to leave your home save for sanctioned groceries, when you haven’t seen friends or family for nearing a year, when the exciting The Serpent location converts to an unremarkable village in rural England. It flies and it crawls.

“Nah, come on,” says Rahim with an eye roll when I cite the “imprisonment” people have expressed feeling in the course this year’s flying and crawling time, in the throes of Covid-19 lockdowns, quarantine, and non-stop news feeds contextualizing the former. “When people use this expression, I mean, I understand it’s coming from a habituated situation, and a comfortable one, and you are in a way ‘in prison’ from what you’re used to doing… But you still have freedom, and I’m in real jail. It’s a whole different thing.”

But we’re not talking about Covid-19, if you can imagine. We’re talking about the human rights stain on American history (and still partially functioning detainment facility) that is Guantánamo Bay. Rahim stars in upcoming drama, The Mauritanian, out in February, as Mohamedou Ould Slahi, a North African with a transient and tenuous affiliation with Al-Qaeda, hastily renounced after its inception, who is imprisoned under presumptive orchestration of 9/11 recruitment, among other crimes. Slahi was never issued a charge, though, during his fourteen years inside the notorious torture complex.

In the film, Jodie Foster and Benedict Cumberbatch play contending lawyers—exceptionally I might add—both of whom, in stylized simultaneity, struggle under the weight of the realizations that the US government is decisively and criminally persecuting presumed terrorists on a very need-to-know, documented though heavily scrubbed, basis. Slahi, in 2005, penned a memoir, Guantánamo Diary, the basis for the film that, following its declassification in 2012, published and translated worldwide in 2015. Slahi did not receive a copy in prison, where he stayed until his release in 2016.

Not TV jail. No cable, no lovers appearing through thick glass to catch you up on the kids, no exercise yard, no due process. Something else entirely. And while Rahim will attest “it felt so good to just be in an airport”, in the context of his recent and short-lived travel—first, a quick family trip to Morocco prior to the second lockdown in France, because he “knew it was coming”, and second, for the aforementioned completion of The Serpent in nowhere UK—we’re talking about an imprisonment truly inaccessible by our current experience.

“The preparation started, like every part that I pick…,” but he trails off, not completing the thought, and it’s evident here that there is no consistency for Rahim’s preparation—how can there be when the absorption is so individuated? This particular role threw him for something of a loop. “My first reaction, at the time,” he says with a wrinkled brow of skepticism, “was sort of a disappointment, because I judged the movie from its title [originally: My Time in Guantánamo]. I’ve been offered many parts in America that were stereotypical, and that was my first thought.”

The film does tend to stereotype—the stylized, swirling sand and the prayers to Allah and the violence—and then you realize you’re wrong, that’s not what’s happening. What’s happening is a sort of reversal, a worming through of the irrational fear and villain-making of the Middle East in recent decades, the reason the film’s imaging feels “stylized” to begin with. Instead, at the core of The Mauritanian—and this filters through nearly every key character—is morality’s conscience, whatever side of justice it’s on, and ultimately, forgiveness. “And when I read it,” Rahim continues, “I cried twice. And… and I’ve discovered that horrible story. We know a lot about Guantánamo. We know what happened. So it’s not a secret. But most importantly, it’s about this man. And the way he got through this with such humanity, such humor, and the way he took over what would have happened to a normal person… because it’s not normal to go through this, to come out wiser than before and holding no grudge with anyone. I mean, it’s incredible.”

The source material, of course, is rich. In the film, Slahi is begged, in the face of mounting torture and a long road ahead of legal side-stepping and obstructions, by the pained yet achingly steadfast attorney, Nancy Hollander (Jodie Foster), to “write it down”. And what yields is frankly sickening. You watch Slahi be gagged and beaten. The colors blur with his vision and the sound design nauseates. You watch him be shackled in front of 500 watt speakers while heavy metal blasts for hours. You watch him be straddled by an appointed humiliator in BDSM gear, who attempts to destroy every fiber of his sexually constructive conscience. And punches, and kicks, and racist foaming at the mouth. You watch it because it was written. This is real. “I remember the first time I talked to him,” recounts Rahim of meeting Slahi, “I got so impressed by his smile, his sense of humor, his nature. Totally heartfelt. I was like, ‘How’s that possible?’ You know? If it wasn’t real, I couldn’t believe it. We talked about everything. And I didn’t want to, I didn’t want to dig too much in those hard memories. I didn’t want to bother him or embarrass him with those awful memories. Plus, I had the book. I had some recordings from him that Kevin [Macdonald, director] sent to me. From then on, I knew the guy and I wanted to catch a soul, which is way more to me, as he is not a famous person—he is not a celebrity. I can mimic him but not too much. So I wanted to catch his soul, his spine, in a way.”

This feels a romantically French step further than your routine character manifestation. His spine. In the film, Rahim’s spine gradually shapes into a capital letter ‘C’, as his gait, his spirit, and rationale are incessantly wrung by the hands of uniformed men and women. “I got into the cell,” he shares on first visiting the set in South Africa, “like a very small cell, and reading about it is something… but experiencing it is something different, totally different. I laid down on the bed, looked at the roof, and all around me. And it’s like a tiny box. There’s only one light, no windows, just a little toilet. Not even a mirror. And it’s very small. The light is all green, and it’s on 24/7.”

We see this a lot of course. This green, tiny box. It looks fucking cold, and it looks fucking harsh. And in several instances, where Slahi has created here something of a familiarity—be it with an unseen prison mate and lifeline next door, or with his pens and pad atop a makeshift mattress desk—it’s hurriedly dismantled, violently sent spilling to the floor, or sent somewhere we’ll never really know… even the home made in this green box is transient and subject to pulverization. Rahim notes that he insisted on experiencing real shackles instead of fake ones, which left bruises for the entirety of filming after just one day of wear. He describes the challenging leaps in language from his native Algerian to Arabic, and his expressing Slahi’s self-taught English in a sort of pyramid shape through the arc of the film—as something of a cotton ball in his mouth thins and dissolves to achieve annunciation despite the horrific treatment.

The treatment of prisoners like animals cuts a certain silhouette, of course. “And then I did a drastic diet to lose weight,” Rahim continues. “I tried to isolate my mind from my body. It’s impossible to completely isolate, self-isolate… and not talk to people while prepping a movie. So it’s impossible. But inside of me, I was trying to separate—isolate my mind and let it, you know, find some truth. But when you get on such a drastic diet, you reach a point where the emotions, you don’t even control them. They pop out. And then trusting my guts to lead me to what I feel could be truthful.”

Truthful is that this is one of those “beyond the limits” stories. We know these. Stories of uncanny perseverance and strength. This person lifts a truck while their screaming infant is wedged beneath its squealing tire. This person lives on semi-poisonous berries in the Wyoming wilderness for ten days. This person takes three bullets to the stomach while charging an assailant, and lives to collect the medal and pop a Christmas photo with no obvious changes. Still, who the hell are these people? I ask Rahim if the resilience demonstrated in Slahi is buried within all of us. He considers, then declares resolutely, “No, I don’t think so…” Then he rethinks the question, “I think we all have this inside of us in a way. How can I put it? It can be revealed when you have to go through an extreme situation. And that can help you, but it has to be fed by something else. For example, this is faith, or the faith in the rule of law—the facts specifically about him, the fact that he is innocent. How can you go through 70 days of torture if you’re not innocent? But I think that every human being has this inside of themselves.”

Conversely, might it be ascertained, then, that every human has inside of them the ability to torture? The Serpent’s Charles Sobhraj, who earned his nickname after repeatedly slithering from the claws of the law, is a candidate to consider—an arguably glamorized and pedestaled candidate whom The Guardian just reminded us, during a profile of Rahim, that “as recently as 2014, GQ magazine ran a splashy interview with this ‘funny, enigmatic, absurd and engaging’ psychopath”. Rahim, however, had no desire to meet Sobhraj, regardless how romantically alluring a Nepalese prison visit might have sounded. Why? Because of basic decency. “Nobody should do this,” Rahim remarks of torture, “no government, no kingdom, no one. And plus, this is our democracy. We’re not supposed to do this and it’s completely inhumane. I mean everybody has to be judged for what they did whether you’re innocent or guilty but being tortured? C’mon, we’re not animals, it’s awful.”

Earlier, when discussing the extraordinary physical duress that Slahi suffered, Rahim speaks of the depths of depletion to survive: “It’s instinctive, it’s animal.” On the flip side, he tells The Guardian he saw Sobhraj “as an animal” in order to assume the icy galant and cold-blooded remorselessness exhibited by the killer in the media, court filings, and so forth.

We’re onto something here. Fundamentally, in just these two stories, we’ve animal ends demonstrated on opposite points of the behavioral spectrum. And it would seem Rahim is seeking to fill that vast pocket in-between, where we as viewers, spectators, or readers can’t fathom the far reaches… but can perhaps understand our species’ capability of going there.

To that end, Rahim affirms that the depths of his preparation for Slahi equipped him with a new sensibility for accomplishing filmic extremes. “Sometimes it’s very hard for an actor to reach their emotions,” he shares. “It’s strange when you’re here laughing with your friends and then you gotta be in front of the camera, and pretend you’re so sad that you have to cry or go crazy—it’s tough sometimes. In this particular case, I remember fasting led me to a range of emotions that I never experienced before. At some point, it can be hard for you to memorize things because you don’t have enough energy or vitamins, but emotionally it leads you somewhere. You don’t go and pull your emotions—it’s the other way around. And so if one day I have to play a really emotional scene… I’ll just fast, I’ll just starve for two days.”

We’re of course in the business of entertainment. Nonetheless, moments like these—fasting for role preparation, portraying people who do sick things to others—tend to ask: what’s the point of all this? Rahim has leaned toward artsier French films over the last decade, because, as he alluded to earlier, most roles, not shockingly, offered from the US tended to be those of stereotypes (though he did dip his toes into the terrorism theme for an English speaking role as an FBI agent in Hulu’s 10-installment series, The Looming Tower, in 2018). Surely he enjoys what he’s doing, cherishes the process, and feels blessed. But the sum is greater than its parts, right? I ask about the ability of cinema to influence people’s awareness around real issues. Perhaps in the modern news age and digitized everything, it takes a stylized, punching capsule like The Mauritanian to really jar people’s sensibilities? “Of course cinema has that power,” he says assuredly, though with a measure of caution at sounding hyperbolic. “I’m not saying cinema is made to do this, but when you have that power, it’s a popular art, it’s the easiest way to talk to people. Yes, cinema can do this when it’s made with faith and justice and when you’re truthful. It can be stronger than a documentary sometimes.”

Rahim is a father of two with French actor, Leïla Bekhti, whom he met on set of A Prophet (that scenario is non-biased beyond the reaches of Hollywood it would seem!), and you can imagine he’s a pretty good one. What informs these reads of contemporary men? Well, a lot of things I suppose, but I’d venture to say the most percolating is a gentle, mischievous demeanor, one you can envision consistently engaged, wrestling or crafting or cooking up all sorts of wondrous imaginings late at night that lend to sound sleep as opposed to something else. And while his CV boasts of realism, Hollywood is yet to see a family-focused manifestation of him on screen, or a role as something of an everyman (Judas opposite Joaquin Phoenix’s Jesus Christ in 2018’s Mary Magdeline doesn’t quite cut the mustard). This was soundly present in France’s Our Children—in the company of a remarkable Émilie Dequenne—though again a pivot point is the meshing of traditional French roots with the geo-ethnic mix that defines so much of the complex contemporary national identity.

How do we get beyond the political? We know that most often the US machine would sooner spawn a superhero film or redo something that once filled seats (albeit with three times the budget), but perhaps the upending of the world’s health concern, the institutional implosion we’ve seen with the latest civil rights movement, which rippled abroad, will germinate a desire for more genuine, character-driven content. Where the white guys aren’t the only ones playing the lawyers, and Rahim isn’t stuck driving a taxi cab. He takes polite issue with my example, though, and perhaps illumines my own problematic American wiring of perception that we are what we do, we are where we come from.

Instead, he says, it’s in the writing, and it includes anyone who touches the process of making a film. “I think we need to tell stories about characters, and not only, for example, whether you’re Black or White or Arabic or Asian. Usually there’s influence that leads a story and an environment to something more political that finally narrows the possibilities of telling stories. For example, in France when I have to answer that question, I usually say ‘Oh, you want to tell the story of a North African or French-African guy—just try not to always focus on where they’re from, why they’re here, the social problems, the political problems.’ Nowadays, in our society you can find Black, White, Arabs, people from all over the world in different jobs, in different positions in every structure. If you tell the story of this guy, for example, like you said, ‘the taxi driver’—it could be everybody, as long as it’s believable… why not? We have lawyers from every ethnicity, bosses, cops, criminals as well, and it might be a good direction to start with.”

It’s not what, it’s who. In retrospect, there was an identity reflected back in that Beverly Hills pool that winter afternoon a decade ago, and it probably read to Rahim as undulating as the palm fronds draping the austere back yard. And while an industry, and a planet, may have a long ways to go, it could also be said, at this perverse moment in time, they have a lot to look forward to. From his locked down home in Paris, where he leans into an iPhone as if it’s a source of heat, the laugh lines making frequent appearances, and the hands of an artist continually helping to sculpt his thoughts, one would like to come banging on the door when this is over—because it’s always a small celebration when this is over— and treat him to an apero of Pastis, out amongst the sunsetting city.

That will have to wait, of course, but I do propose ending the interview with optimism. I ask the actor what he’s most looking forward to when the world is back to organizing sporting events for 80,000 screaming ticket holders wont to hug and slap high-fives when the favored on the pitch wins favor, back to pinging 175,000 flights a day from hub to hub around the planet, or popping by your new neighbors for some English breakfast and biscuits. Rahim smiles wide at the prospect, almost not sure where to begin, but then boils it down quite simply. “Truly,” he says, “I came to realize that what I miss the most is coffee and cigarettes on a beautiful terrace every morning. I miss it, and I wish I could just start my day like this. I never realized how important it was for me because it’s my moment: I sit down, take my coffee, and light a cigarette, think a little, give some calls, and then start my day. But yeah, I would go for this first, and then I would go for a movie, and then I would call my friends and say, ‘Let’s have a party guys.’”

Photographer: James Weston

Stylist: Nicolas Klam

Hair: Nabil Harlow at Calliste Agency

Makeup: Anne Bochon

Styling Assistant: Augustin Puzio

Location: Pullman Paris Centre Bercy Hotel