F L A U N T

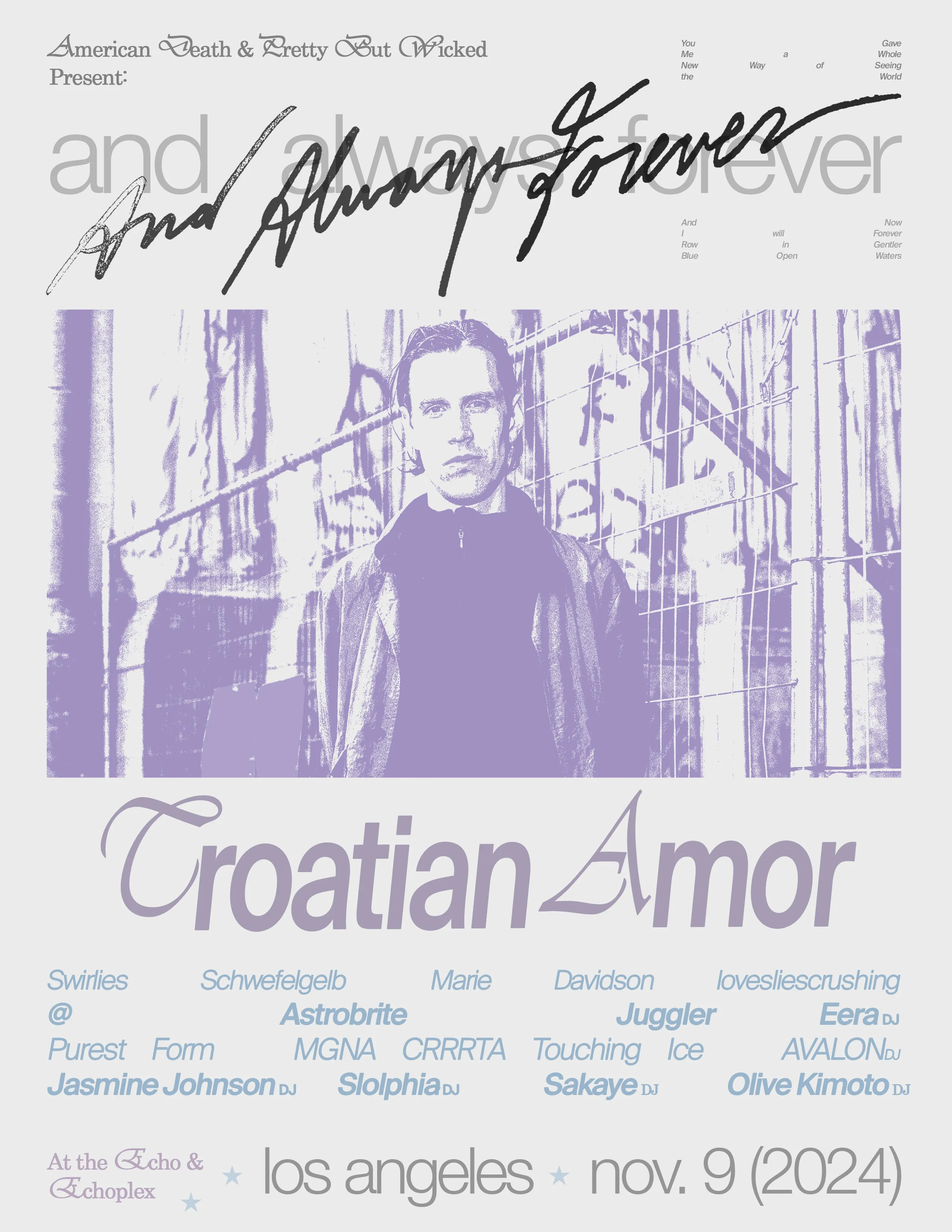

This Saturday, you and everyone you know will be at And Always Forever. Taking over both stages of The Echo + Echoplex, in its first year and the first of its kind, AAF is a love letter to the Los Angeles music scene, wherein dense, turbulent, and exposed soundscapes of shoegaze will marry into the pummeling percussion and pervasive force of today’s experimental techno. The single-day festival welcomes legacy acts, the Swirlies and lovesliescrushing, as well as rare performances from overseas electronic acts, one of which is Danish electronic producer and artist, Croatian Amor.

At the center of the Scandinavian experimental scene and co-founder of Posh Isolation, Loke Rahbek’s Croatian Amor delves into the abstract, delivering a dynamic interplay of existential contemplation and surrealism, oscillating between ecstasy and despair. Each composition waxes poetics on longing, solitude, and the ephemeral nature of time itself, ultimately transcending mere sonic pleasure to a philosophical meditation on existence. Known not just for Croatian Amor, Loke’s artistic output varies from the surreal might of electronics and performance art of Damien Dubrovnik to the nostalgic new-wave sentiments of Lust for Youth.

On the cusp of And Always Forever, Loke speaks with the cofounder of And Always Forever, Davis Stewart. The LA-based musician and promoter started his own label, American Death Records and curated AAF as a chance for LA's budding music scene to perform alongside those who have inspired it. His own industrial sleaze project, Touching Ice—drawing influence from electro clash acts like Schwefelgelb and, of course, Croatian Amor—will also be playing this weekend. You can find tickets here.

See here, Croatian Amor and Davis Stewart unfold what’s truly forever and find meaning in the dissonant.

Davis: When you were last in LA, did you spend any time here or was it just playing shows?

I still have friends in Los Angeles. So, I spent quite a bit of time there and it is always, for me, a weird place. The way you interact with the city is so different from what I come from in Copenhagen. It's the in-between, you go out your door and you figure it out: bike around or you walk around and you just come up with your day. That's the way. And being in a city where there's basically no sidewalks, it's very confusing to me. It requires a different way of thinking almost, interacting with the city completely changes the program. But I also, I've never disliked it. I just was baffled by it.

I remember the first time I was in Los Angeles. I went and we were up at that observatory, the Griffith. Then one of these wildfires and outside of San Diego and the whole, you could just slightly sense the smell of smoke in the air. We looked, it was evening and we looked out over Los Angeles and all the electricity from the city just made it look like the whole city was on fire. It had a big impression on me.

Davis: Was that the inspiration for “LA Hills Burn At The Peak of Winter”?

Yeah, I think that memory of standing there and feeling like the end of the world was not something in the future.

Davis: I can’t imagine visiting here with all the apparent decay, but all the mysticism attached to the city.

Bree: I think a lot of your themes explored through Croatian Amor align with the intention of And Always Forever, like finding the beauty in the brutal. What is so stimulating for you about longing, existentialism, and nostalgia?

I don't know if it is stimulating, but I guess they're part of the fabric of life, they're just built into the curriculum. I guess I don't think about it so much. I think more that I just go into the studio and I just play however I feel. I would be lying if I said that I go to the studio with a concept of longing in my mind. I usually just go and try to make sounds that I think are cool. And then at some point, it feels like it's done.

I guess I have a tendency, everyone does. A tone or a color or something that their stuff just automatically comes out in. I think everyone has this core thing. I have this experience that I have an immediate reaction to people's work when they do the work that they're supposed to be doing. And I don't think we choose our own color or our own tone, but I guess mine does have a little bit of a blue note. And, this is always the stuff where I think, ‘Oh now I like it. Now I feel, that maybe it sounds like that.’ I think about the human experience, but I think the time I think the least about it is when I make music.

I think that's part of why I like making music, I think a lot about this, It doesn't work in Danish, but it works beautifully in your guys’ language. To play is what you do when you make music, but to play is also what kids do. I have a three-year-old son who was just running around half an hour ago, now he's asleep.

Bree: It seems really natural and perhaps a view into your subconscious because it does seem instinctual.

I think just all those things are sometimes there, deciphering or analyzing is not, doesn't do — I love this English children's book writer, Philip Pullman, who talks about how before he was a writer, he was a school teacher and he had to do these — when you have to break down a poem, you have to figure out what it's about, as everyone was forced to do in school at some point. He just has this beautiful way of saying that once you've done the poem. Once you've pulled it apart and dissected it, it's never really that interesting. And he says, ‘There's no wonder it's not interesting. You just mutilated it. No one's going to tell you a beautiful story after you butcher them.’ I think a little bit of that applies to art. That bit that we don't know what it's called that we can call art because we don't have another word shies away from too much dissection. I find that when I try and when I read other people who try to do that, it's never really interesting what comes out.

It has to stay hidden. You said, “subconscious.” I think it's a nice way of putting it, in the underworld where it belongs. Let it be there and let it just pop out into music once in a while. I think that's a better way of treating it. It feels like it's shy and I want to stay on good terms with the muses.

Bree: I think perhaps if it, your message or whatever you wanted to say, could exist in any other medium or in any other way, then you wouldn't have written the song.

You said it perfectly, and I think that's where a good artist knows that you cannot print it on a t-shirt and you cannot write it out in a text. It sort of lives in this weird in-between world, sort of the same place where the dreams, monsters, and fairytales live. All that stuff. All the good stuff.

Davis: Do you find such an emotional process or do you turn your brain off when you're making visual art as well? Or is it more of a struggle for you to work in a visual medium for the Posh Isolation or Croatian Amor?

When I was a kid, I wanted to be a painter. And all through my early teens, I was certain that I was going to be a visual artist.And then at some point, I was introduced to experimental music and live music. And I was so excited. Then, I started making visual stuff and I started making noise. At some point, we started a label, and I got to do all the graphics for the label. It's been a nice way of staying in touch with visual language, but outside of being a visual artist. I enjoy doing that stuff. In a way, I think my brain works more visually than it does sounds, so I think in some ways it's easier for me. I don't know. It's just maybe different brains you use for different things. When I make music, if I think about anything other than sounds when I'm in the studio, I just think about what the color is.

Davis: A lot of your producing is done on a DAW, are you more of a tactile person?

No, no, I'm super DAW now. And I'm preferably not really in the studio all that much. I think just the fact that you don't need any fancy machines and you don't need any soundproof rooms. You just need headphones and a functioning laptop. I get on a kitchen counter or something like that. It is better for me. On a plane, I made a lot of music on planes last year. I think, ‘You just have an hour, I'm just going to do something.’ That is usually where all the good stuff comes out or it's in the fancy studio with all the fancy machines and stuff. Maybe it's like an antithesis, I don't know.

Davis: It's not like stepping into the isolation booth. It's more like, ‘Here's a USB mic in your kitchen. Give it a shot.’ I think that speaks to why y'all's music is so captivating and interesting that it's based on emotion rather than the technicality of things. It still captures a human essence in a way that's universal. Are most of the Posh Isolation members more classically trained or is it a similar quote-on-quote, “nonmusician approach?”

I would say it's like a half-half. There's definitely like, CTM (Cæcilie Trier Musik) who comes from playing cello her entire life. And [Frederik] Valentin's not classically trained, but he can play most instruments. Scandinavian-style metal, they can play most instruments. But then there's also a good bunch of us that have no idea what we're doing. You find out that over the years they are different roads, but one doesn't seem to be necessarily better than the other. It's just different, but I'm very happy to have like, quote on quote, “nonmusicians.” I guess I just never really got around to playing, and now I feel like I've done okay so far.

Davis: I have another question I wanted to ask you. How would you define pop?

Yeah, I think everyone sort of made fun of me because I always say, “Oh, I just made a pop song, like I made the greatest pop song, and then, yeah, no, it's not.” But, I think for me, it's a very special world. And I think these, I still even, even a lot of pop comes up like even sort of mainstream pop comes out. I guess pop is sort of popular, isn't it? And this thing happens when someone taps into something and then all of a sudden can speak a language that touches all these people simultaneously. I think that's very close to…I would call that magic in a way.

Even if there are some boring producer types that sit in some place and have all these ideas of how you get to that point. I think when it happens, when you're in a room, where there is that sort of collective experience, I think that's really what it must be about, this sort of human incarnation, no? And I think that can come from a pop song. I think it can come from a lot of things. But I like to think of pop like that. This sort of collective experience. I’m actively trying to make a pop song, that’s what I want to do.

Davis: I do the same. I'll like feedback on a guitar and sing over it, and I'll send it to my family and be like, “Hey, I'm trying to make some pop,” and they're like, “Bro, what the fuck are you doing?”

It's boring to always talk about this pandemic, but it really did change something for me in the way I approach making music. Because when there was nowhere to go and you had to be at home, the only thing I felt like doing was to make club music. And I had always sort of been on the ambient shift in the club. That was natural for me. And then all of a sudden I was like, it’s not the room that I miss, it’s not the people sitting down, having what is most often a very singular experience in a way. What I missed was being in this room of collective energy exchange. I have never gone to a club less than I do in my life now, but I'm really attracted to the idea of club music. I think it's a mysterious world for me because I have very limited experience in making that kind of stuff. I feel like I'm trying to navigate a language that I don't fully understand. And I think that's very exciting.

Davis: It's interesting how massive yet faceless that culture is too, and regional. It really identifies with graffiti scenes to me. They are both similar in a very cool way. It's like a whole little world that you have to kind of bludgeon your way into to be respected.

I like that you reference graffiti. Before music, I was just always around that stuff. That was all the people I hung out with. And I think for me, like Aphex Twin and a lot of my early introduction to electronic music, it felt like graffiti writers also in a way. They were these sort of mysterious characters that you couldn't engage with in any way but their work. And for all the writers coming up, that was the same thing. In some of these legends, you had to bond to their particular way or something. And they became these sort of weird ghosts. And what I still like today about electronic music is that it does sort of a thing where it's not so much about what the artist wears, or what he likes, what she likes to eat for dinner, it's more about sound. So it's more collective in a way. Someone said that when club music started, people went from looking at the stage to looking at each other. And I think that's a nice idea, no? And of course, it's an ideal and an idea, and clubs are many different things...

Davis: It's an ethos to approach it with.

Yeah. I do still think that electronic music has a sort of a history of facilitating an emotion or an environment rather than having these very strong narratives. Like “I do this,” or “I fell in love with this person.” Not the typical way of communicating popular culture, which can be a little bit limiting sometimes.

Bree: I think something that I kind of wanted to talk about is the idea of club death. What do you think about the future of live music?

I think the future of live music is going to be great. I don't really engage with much of that stuff. I mean, I play shows and we put on shows here in Copenhagen, we do some showcases around, and that's more or less all the shows that I go to. I don't know if I have anything clever to say. I think there's always going to be a need for these collective experiences. The whole big sharks eating the small sharks — I'm certain that that's happening, but I don't really know much about it, to be honest. I think more and more, I try to just do the things that I like doing.

I don't even know what my own future looks like. I would hate to have to answer for the future of live music. That's a big one. I think there are these moments where it works, where we have these experiences where it's undeniably a good thing. They’re one of the few things that I cannot come up with any argument against. Getting together, and experiencing a sort of Dionysian art, I think it's absolutely vital, and it's been around forever. I think it's not going anywhere. And I think, of course, there's always big ones and small ones and in-between ones and bad ones and great ones. But I think this sort of concept is just we're a species that relies on contact. It is in our DNA. We need these other people in order to experience ourselves. A club a theater or a religious ceremony can facilitate that. I think it will be great — it will be weird for sure.

Davis: The whole reason we booked this fest is I got an opportunity to do it. Basically all the undercard, most of them are LA bands, so then we just like to talk about bands that we all love. I was like, ‘Oh I'm gonna try to get all of these bands that we love, like you, loveliescrushing, the Swirlies, Schwefelgelb, some of our favorites, that heavily influenced us. We definitely wanted it to be LA playing and opening for all the people that we feel we owe it to. I'm interested to see that collective experience and how everybody interacts with one another and getting to see some of my friends meet people they like and say, ‘I started my band because of you.’

That's always so special. That sounds like the perfect way of doing it. Well, that's basically what Mayhem has always been, no? On Thursday there's a show, a bunch of our friends opening up for some American guy, and it's a way to get everyone to play, but also to pay for this guy to come over from overseas. It's just so fun — there's no better way.

I think that after running a record label for all these years, it's very hard for me to get excited about seeing a vinyl record for the first time or getting a master back. These moments where it's about the shared experience.

Davis: Do you feel the same way about all your bands?

Not so many bands anymore. It wasn't a conscious decision. There's so little time now and being in a band takes a lot. I like these collaborations now because they create this fun space where everyone gets to do something that they don't usually do really. When in a band, you get to do that at first, but then the ambitions and the ideas and the concepts come sneaking in pretty fast I found. This is just a lot of human stuff. I think getting a room together is about being equally invested and having this collaboration is kind of in its nature. You don't need it to be your magnum opus or something. You can just be having fun.

Davis: Yeah, I’m like, “Hey guys, we have to make rent this week.”

It's sort of a very pure space. And I think I like that more. I am less and less interested in this, but I was pretty invested in it when I was younger – this image of the artist as this sort of person who bleeds out this thing. I think sometimes we make mistakes…There can be things where it begins to feel really important. It's sometimes not the art of talking anymore, it's the personality. And personalities are fine and egos are fine, but sometimes they leave a bitter taste in the pot. And I think trying to keep it at least in check. Because it's natural, of course, we want to make good things, we want people to like us. It's sort of built into our DNA, you know? But, I think artists…I think it's best on its own. It's best kept away from all, from too much of that stuff. It dilutes it a little bit, I find. Sometimes you hear, I have this experience once in a while, that someone is trying to say something, but they're taking up so much space in the music that there's really no place left for the listener to stand. And I think more and more now, I think about this. There should be enough air for both the music and the people listening. Cause you know that room where all the air is already… But I think just keeping it, for me, very pure and a little bit naive maybe, is good. I keep coming back to this thing that your language says. That it's play, that music is just having fun, no? Let's go play.

Davis: On that, I want to know, what's your Oasis opinion?

My Oasis opinion… I was never super big on rock music when I was younger. It was actually when I was in Lust for Youth, that both Hannes and Malthe were obsessed with Oasis, and they sat me down one day and showed me some YouTube videos and stuff. Just interviews, like best of interviews. I thought it was the funniest thing I'd ever seen in my life. Then all of a sudden, I got all the music just after that. Now I get it.

Davis: It's so funny that your analogy of playing and someone's ego becoming too big. Then I look at Liam Gallagher and that ego almost feels like he's playing into it and that's the joke.

Yeah, they fuck up my theory a little bit. Maybe you just have to be an obnoxious duo from Manchester to be able to pull it off.