F L A U N T

When I was 21, I bought a fancy perfume during a trip to Paris. I hardly wear it now, for I fear that with each spritz, I’ll surrender part of the memory of that trip to the atmosphere — turning it from the reel in my head to something thinner, less mine. Every time I smell it, I’m transported back to the cobblestone street in Le Marais where I bought it, to the unseasonably warm March mornings in the Rodin sculpture garden, to dinners at scene-y restaurants with old friends.

This particular type of information storing, in the sensory memory, is rich and lasting. And the senses, some suggest, are inextricably linked to emotion. Ellen Reid, a Pulitzer Prize-winning composer and sound artist (and recently inaugurated curator of the Phil’s annual Noon to Midnight festival, a 12-hour endeavor featuring art installations and music performances in Walt Disney Hall on November 16th) creates soundscapes and music with this tacitly in mind—place as the common thread and the echoic hippocampus of her world-building.

Reid grew up in East Tennessee, and though she didn’t begin composing music until her undergraduate years at Columbia University, she was constantly learning through sound. “The landscape was so musical. There were katydids and cicadas that kind of do this crazy rhythmic looping in the summer,” Reid explains of her birthplace. “You really hear nature — like the way that leaves crunch into your feet or swirl around you.” Sounds hypnotic, doesn’t it? I think, as the city behind me screeches, its dissonant melody creeping into our Zoom conversation. I unmute, allowing it to join us.

Reid laid claim to her place in the music scene swiftly. Her personal oeuvre, unencumbered by the constraints of genre, reaches widely into the imaginations of musicians and music lovers alike. From the orchestral to the ambient, Reid is decisive, thoughtful, and vulnerable in her expression. After graduating from Columbia, Reid moved to Thailand, where she was introduced to operatic composition. From the “really weird, experimental venues” that “exploded [her] brain” in New York City, to the epic poems and dance dramas in Bangkok, Reid has created a rich musical landscape that pays homage to the natural chorus of her natal home, as well as the multi-placeness of her career and training.

Often, place is a necessary comfort; other times, an opiate for our collective distress. It’s about reifying that which is just beyond our reach materially. Place as a lexicon for deciphering our realities. This is what Reid’s work — her compositions and her curatorial effort — is reaching towards (and achieving with profound resonance). It’s a dialectic of the ephemeral and the material. What can we tap into, as audience members, without ever experiencing ourselves? A lot, when the artist is willing to go there, according to Reid. “Whenever an artist speaks about something that resonates with them in a truthful way, it can resonate with other people, whether or not they've been through that experience.”

Now, in a historical move by the LA Philharmonic, Reid has become the first-ever external curator of the Phil’s annual Noon to Midnight festival, which she describes as a “day-long conversation around sound.” Reid’s intrigue was immediately piqued when she got word of this year’s theme: field recordings. “I got on my phone and had this 50-page list of ideas and people and collaborations,” she shares, “like my imagination was just like boom, boom, boom, boom, boom.” On adhering to the theme of field recordings, Reid expresses, “Weaving together some connective tissue artistically throughout the day felt super interesting rather than just presenting beautiful performances.”

And isn’t that the point of it all? Connection through art is resounding on this program. When you look closely, listen deeply, and engage mindfully, it’s also a study in transgenerational memory and placemaking. “The Pan African People's Orchestra has created a program that uses field recordings and recordings to go through the history of them as an ensemble,” Reid shares. With this program, Reid constructed a soundscape that echoes the topography and energetic force of the artists’ communities.

Field recordings, in science and nature, capture an archival, preservative essence in relation to their subjects. They capture that which exists in a single, specific place and make it exportable. Noon to Midnight mirrors this in its approach. Cultural artifacts, like those utilized by The Pan African People’s Orchestra, are intertwined with the singularity of a live performance. The innately fleeting nature of live music is enabled in its purpose to drive connection by the longevity of the recording. “Because getting all of these artists together to do this again is like — it's never going to happen. This is the only day to experience this.”

In this festival, attendees are encouraged to chart their own sonic and visual paths towards pleasure and engagement. Specifically, Reid had the communal experience on her mind while curating the program. She tells me, “ the live [listening experience] is usually more communal. There's this full room of people that science tells us their heartbeats sync up and crazy stuff like that — like the way that we're connecting is beyond what we're even conscious of in a room like that.”

Reid brings a deep thoughtfulness to the curation of this festival. She tells me, “The energy at the beginning of the day is so different than the music you want to hear at the end of the day.” On how she considered the sonic journey that attendees would go on, she asks herself, “what are these different rhythms that we're going through throughout this 12-hour span in a day?” Under Reid’s careful programming, festival attendees are transported all over the world.

They’re almost tactile, her soundscapes. “Places resonate. And so just even imagining it — imagining a place has a resonance and trying to match music for that, that vibration of that place, is really interesting to me as a composer.” My eyes widen when she says this. How do you mirror topographical or visual resonance sonically? Reid indulges my curiosity, sharing, “the first track on [the album] Big Majestic, I was looking at the way that light reflects off of water and trying to create music that took me to a similar place emotionally that that visual took me to.”

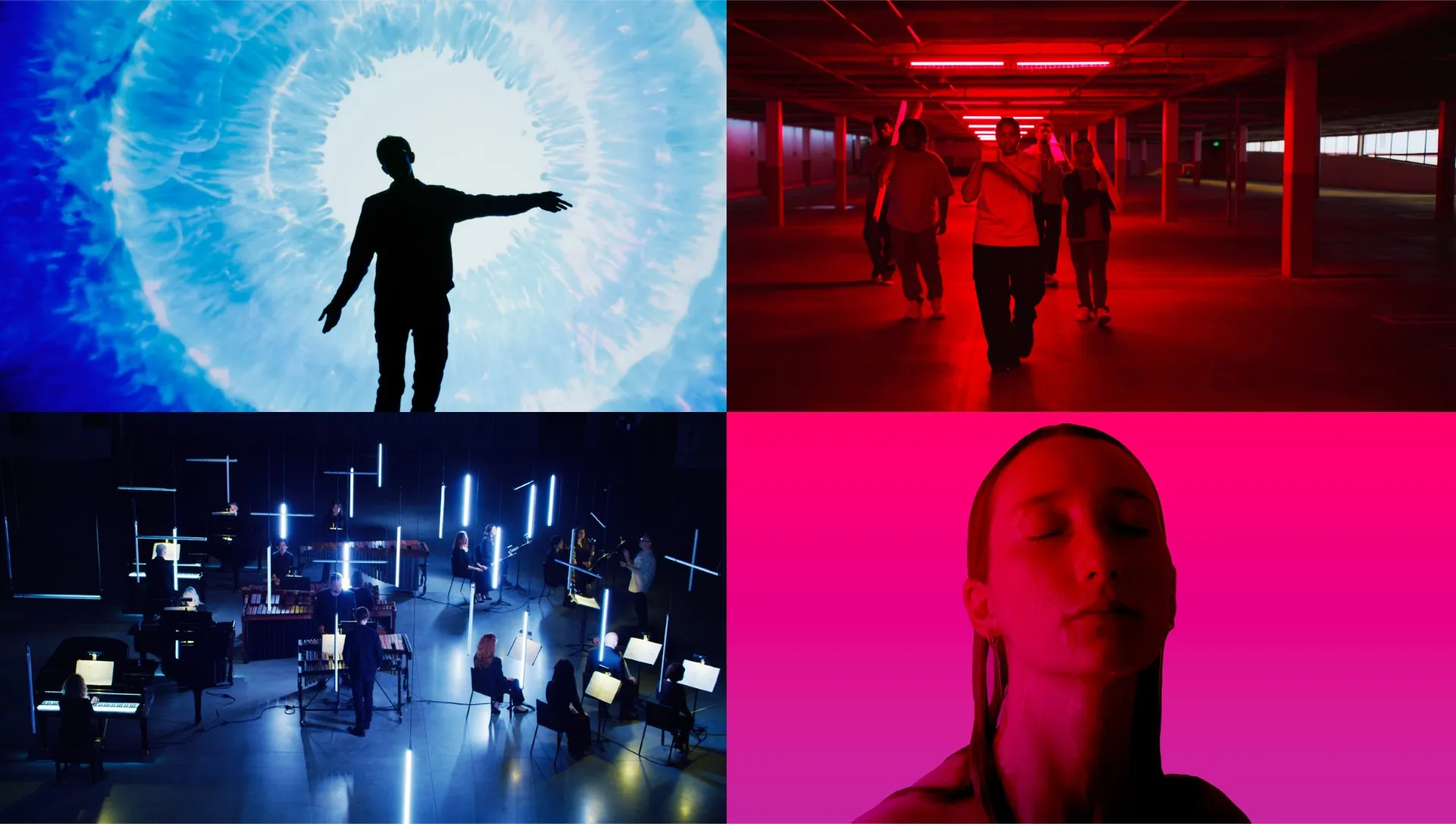

“I worked on that theme and I would put on my headphones and then walk down and look at light bouncing on water,” the composer says, describing the visual as her “collaborator” in composition. This tandem approach is also evident in Lightscape, the groundbreaking multimedia artwork by Doug Aitken at the center of the festival. Lightscape is a true collaboration between the sonic and the visual — a live musical performance by the LA Master Chorale and the LA Philharmonic accompanied by a multi-screen installation of a feature-length film.

The film traverses the American West, a “non-linear narrative” confronting the individual’s negotiation between the accelerating modern world and the self. At the crux of Lightscape, the film’s subjects and the live musicians alike are building towards a new, possibly frightening vision of place — nowhereness. The American Dream, Manifest Destiny, the “fever dream,” that Reid explains to me as the driving beat of the film is all, ultimately, an abstraction.

“[In] composing, you're starting with a small kernel of an idea and trying to grow it into something that can fill space and time and capture people's imaginations,” Reid exalts. That’s it, I think. Art that fills space and time. Art that is both felt and imagined. Everywhere and nowhere.