F L A U N T

Photographic language is fraught with violence. Snap a shot. Capture a moment. Take a picture. Shoot a model. So often, photography traps. Little joys snared in a lens, sunlight that once fell in the correct place consigned to pour on its subject for eternity, a body in motion forever smeared. Photographs wrangle in the wild animal of lived experience, convey a moody truth, abduct that lithe being of reality, to be reproduced in the exact spot of detention over and over again. Anyone with a camera can regularly engage in the blood sport. A good photographer knows how to treat a trapped moment tenderly, how to assemble a split-second into a transmutable emotion, for enjoyment, for pleasure or for pain. Paris-based photographer and visual artist Jean-Vincent Simonet is a practiced handler of such business. He graduated as a photographer from illustrious Swiss University ECAL almost a decade ago, where he learned to execute these photographic techniques with a razorlike precision. Though he’s an expert in the hunt, Simonet is not interested in the exactness of the visual world lent to the artist by an HD lens. In fact, much of his current work might not be immediately identifiable as a photograph at all– his post-production techniques, handcrafted and retouched using chemicals and other development techniques, raising his subjects to a point of near abstraction. His work, almost painter-like in its emotive ambiguity, is porous, allowing the subject to seep out, to breathe, to flex its musculature outside of the medium in which it resides.

Jean-Vincent Simonet hails from a family of printers. Not pretty, art-book, luxury printers. Industrial printers. His father, and his father, and his father before that have owned a print factory in Bourgoin-Jallieu, a small region near Lyon in the Southeast of France, since the 1930s. As a child, Simonet would often work alongside his father in the factory, and became intimate with the formidable machines used to produce heavy-duty materials. He’s since used this knowledge to elevate his photographic work: each year, when every European takes that blissful August holiday, Simonet comes to the deserted factory, using machinery to manipulate his prints, yielding results unreproducible with conventional digital softwares. His latest exhibition at Amsterdam’s Ravestijn Gallery, Keys to the Factory, is an acidic, analogue dive into his childhood at the factory, his industrial subject manifesting through his unique manipulation of inkjet, plastic, foil and chemical processes. The collection demonstrates Simonet’s love for the factory, but ruminates on the fact that once his father retires, the legacy is over: he won’t take over the factory.

FLAUNT used two of Simonet’s previous works in our Eternal Flame issue, “Red Vex” (2020) and “Colombes” (2021). We sat down with the artist to discuss the process behind the images featured in the print issue, his relationship to labor as an artist that comes from an industrial background, and how he toggles between mediums:

“Red Vex” and “Colombes” were produced in different years. Can you talk a little bit about where you were as an artist while producing both of them?

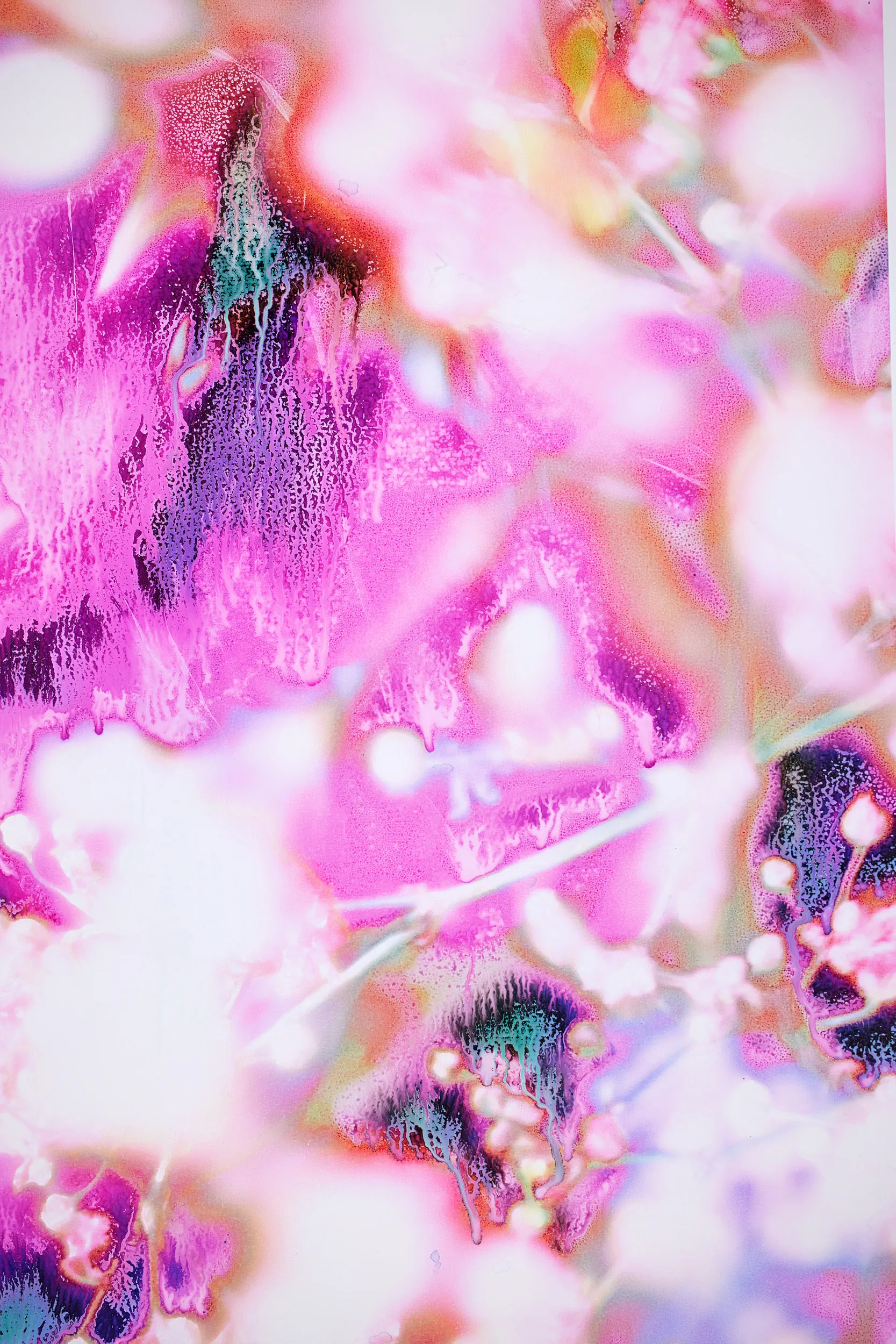

So the "Colombes" work is a still life. Actually, it's a macro shot of jewelry. A friend of mine–a really talented jewelry maker in Paris called Colombe D’ Humieres– is creating these organic, medieval kind of unique pieces. I had covered the work for a fashion shoot, and I was like: “Oh my God, I really feel connected to this work. I should just ask her if I could get some more and just make some weird still life out of it.” I like the fact that you don't necessarily recognize that it’s jewelry.

The “Vex” shot is something completely different. It's a collaboration I did quite a while ago for a porn publication called POV paper from Switzerland. They do a lot of things around porn, but not at all mainstream. This girl Vex, she's a director and she's an actress. She has a really amazing production company called The Four Chambers. There was a huge interview with Vex, and we shot some images that weren’t this image. They were published in POV, but I had so many great pictures of her that I kept on printing. Those images with Vex are so strong and so powerful that I kept using them, printing them to experiment with new ways of doing images. It was a nice combination. Formally, it works quite well. But also in the whole span of stuff that I can do, [the two works] provide two different angles of my art.

There's a different sort of labor involved with an individual artist’s act of creation versus segmented, industrial-scale labor. Growing up around the factory, you must have borne witness to both. How does your art negotiate the two, or put them in conversation?

It's actually one of the big underlying things at the origin of the Keys to the Factory – this idea of values and work. Basically, when you are dealing with the industry of printing, like my father, my grandfather, and my great grandfather were doing, it means working a lot, and earning so low and working from five in the morning to eight in the evening. I mean, it's this kind of industry where the rules are quite a lot of pressure and not a lot of fun. You have to work a lot when you're not used to it. It's not the same way of dealing with your time. It influenced my way of developing a project–to push a lot, to retry, and to force myself not to be satisfied with what comes first.

My work is about production. If I don't do stuff, nothing happens. I'm not a conceptual artist– I need to produce tons of stuff, tons of bad stuff. At some point, something interesting will emerge out of this mass of things. I think this way of behavior is kind of linked with this education that I have. If you wanted to get some money, you needed to work during summer, you know? Nobody’s going to bring you home at nine, you're going to leave with your father at five in the morning– that kind of thing. In these cases, there’s this idea that during all those working hours, it's so boring that your mind starts fantasizing. And that's maybe why there are so many views of the factory– it’s our daily lives. Daily still-lifes. It's so repetitive and so boring. You needed to escape in a way…It’s also something that I think is disappearing. I mean the oldest industries are already gone. They’re already in the past.

People that aren’t familiar with you might not even be able to tell that it started as a photograph– it could almost be construed as a painting. Can you talk about how your relationship to photography as a medium has evolved over the course of your career?

I was trained as a proper photographer. I did my studies in ECAL in Switzerland. It's this university which is quite known to give you a lot of technical skills. The whole thing, it's not very art related. I mean, it is, of course, but it's more technical. At some point, I started to use photography as a raw thing that could be transformed. I try not to be amazed by the image itself. Like some photographers, they are crazy about this beautiful print of a thing. I think it's kind of fake– it's like a varnish, you know? [I try] give more depth to that.

I realized that I had this wonderful tool that was the factory, and from one project to another, I developed all these techniques that allowed me to transform the surface, to have this pictorial, painterly feeling. It's kind of an economic class kind of thing, trying to destroy the picture. There is this idea of destroying the thing to create something new. This idea of mistakes, this idea of hijacking industrial high-hand printers to make something, is kind of the opposite of what the printers are made for. To go against the predictability of photography– it’s something that I like that goes against this gimmick of the photography world.

I am much more interested in painting, drawing, installations and things like that, but I love doing commissions that come from photography. I didn't fully escape the photography world. I'm like a ghost going from one scene to another. And I mean, I don't want to split on one side or the other. I like this gray zone.

What’s next for you?

Now, I’m researching the creation of materials used to make images in industrialized contexts. I’m fascinated by the idea of a fishing lure– images are lures, in a way. I’m shooting a new series where I work on the lures that are made by fishermen, those that have crazy colors. They are real craftsmanship. They are mimicking what could be a fly to get fish, but they don’t even look like flies. They are even actually real replicas. They look different to be more efficient. I really try now to make a kind of a galaxy of concepts that could work together and then shoot.

Does your thesis often change as you're interpolating it through all of the mediums that you're putting it through–do you try to ensure your art is articulated exactly the way you wanted it to be?

I mean, I don't know. I'm still into bizarre ongoings and processing them. I don't want to give all the keys to my work. People bring things to the work they thought were lying underneath, but the artist is not fully aware of it. There’s always space for others to find things. I want to bring something complex, not fragmented.