[](#)[](#)

Shooting At The Mountains of Madness: The Lost Work of Diane Pernet

Flaunt Present Four Unearthed Photographs from the Archive of the Artistic Polymath Diane Pernet

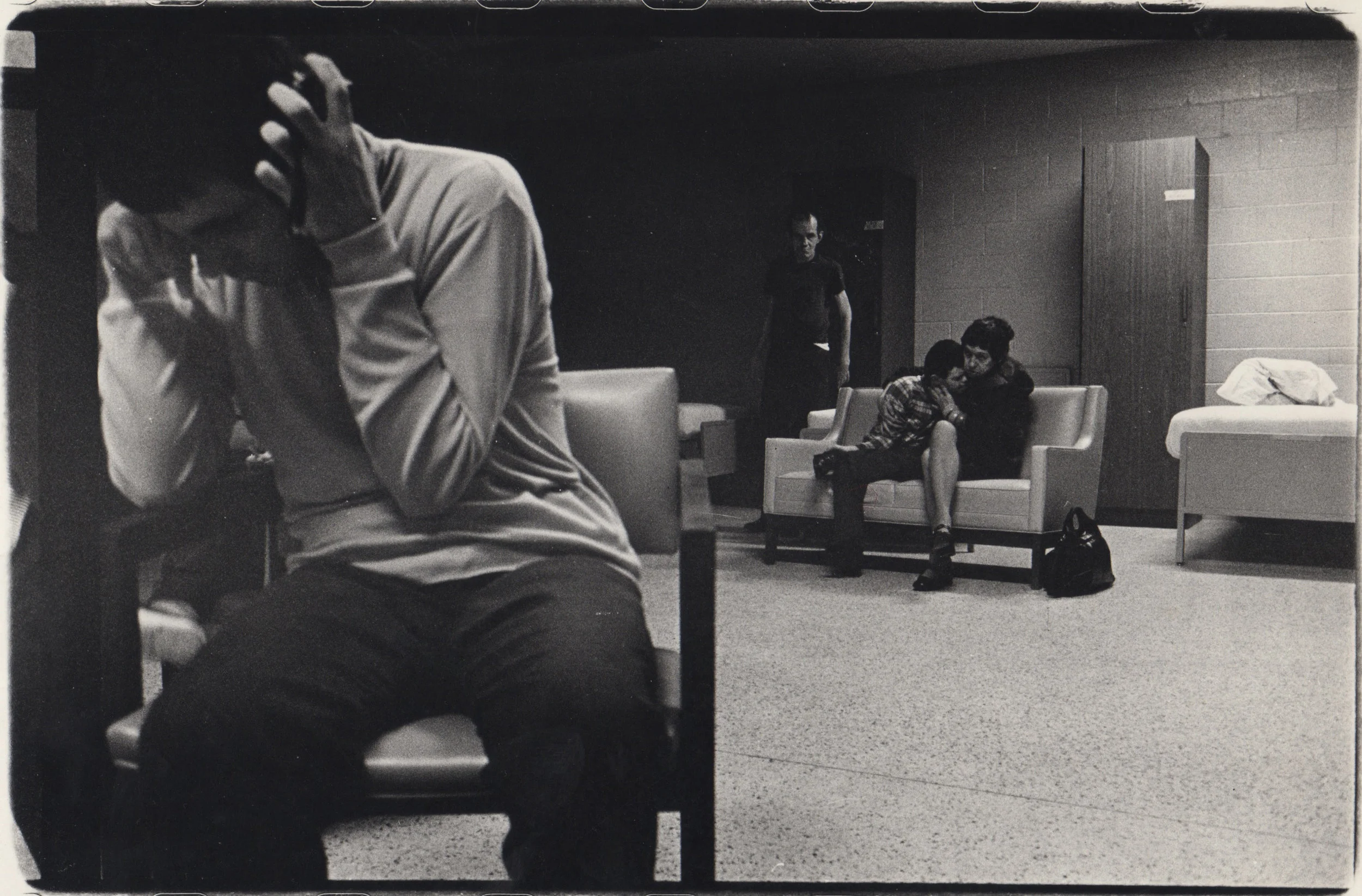

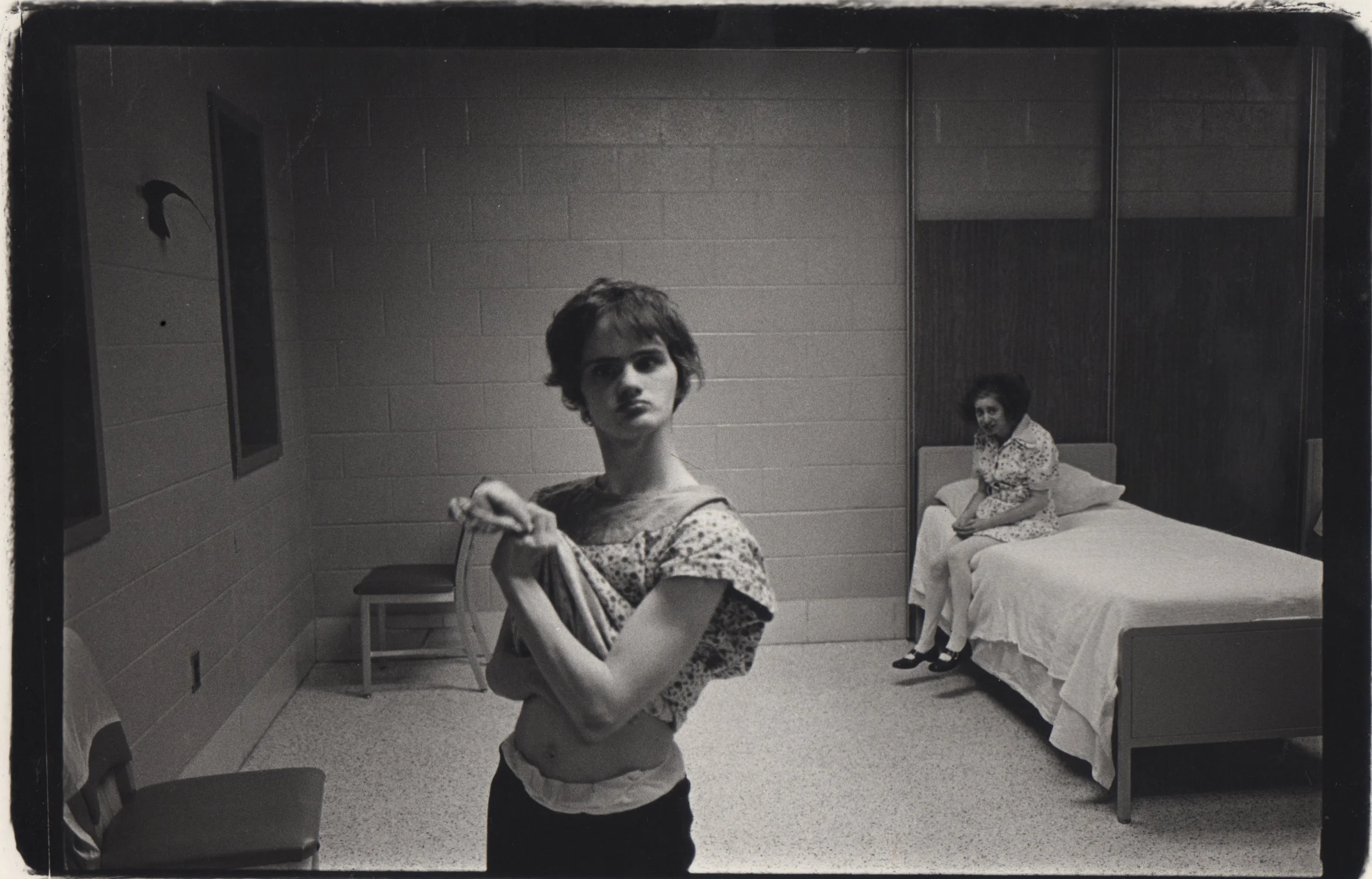

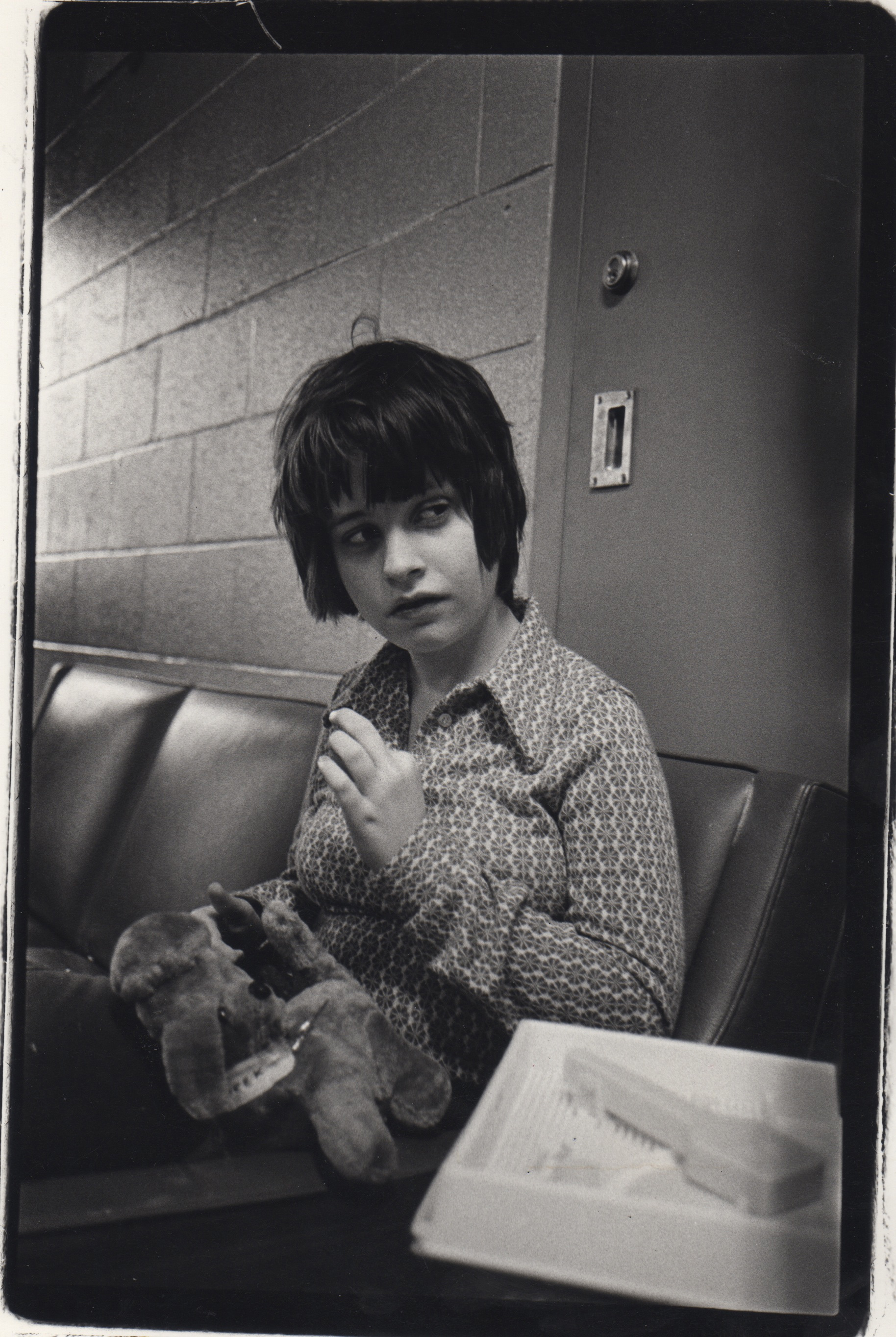

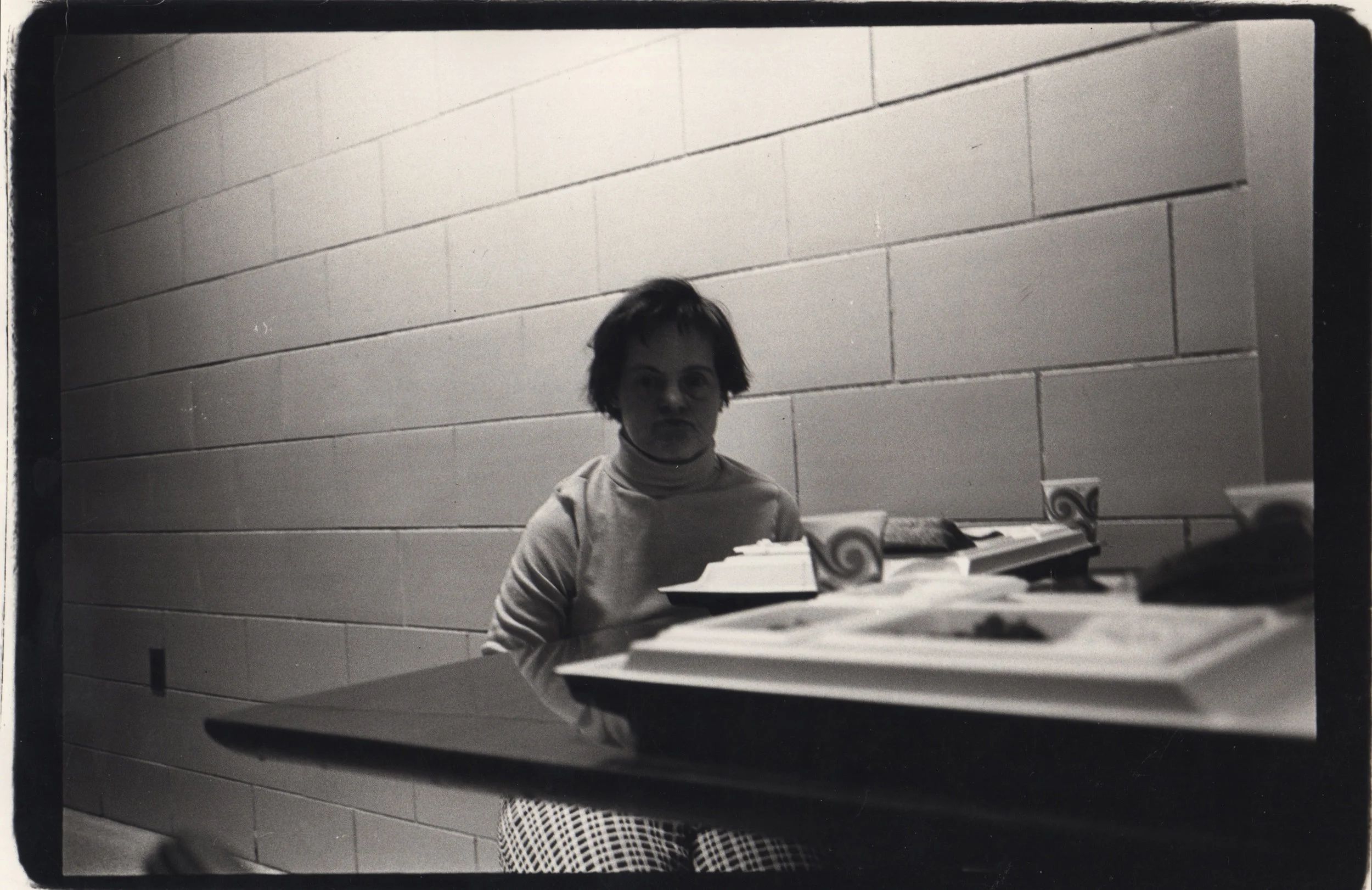

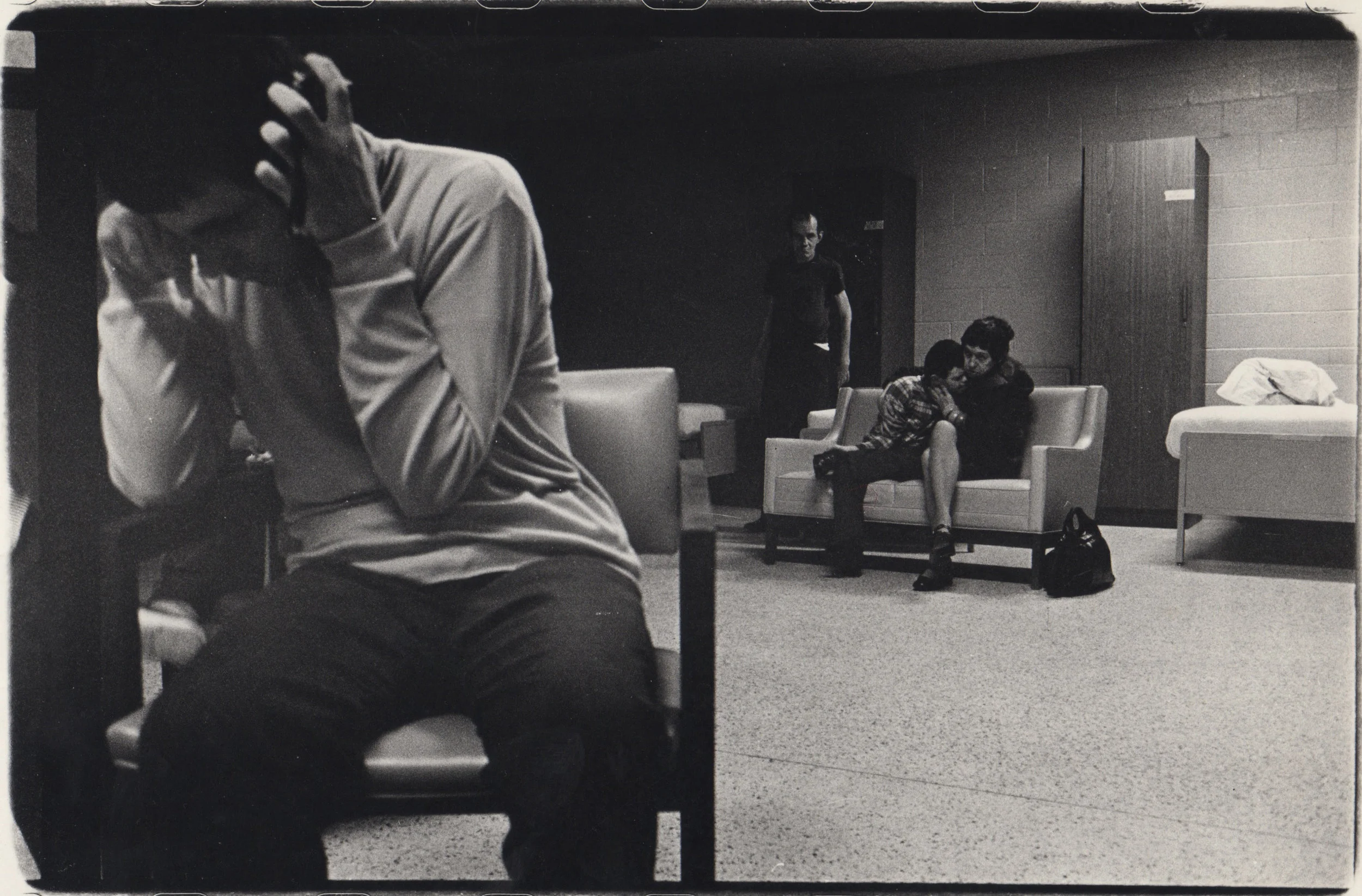

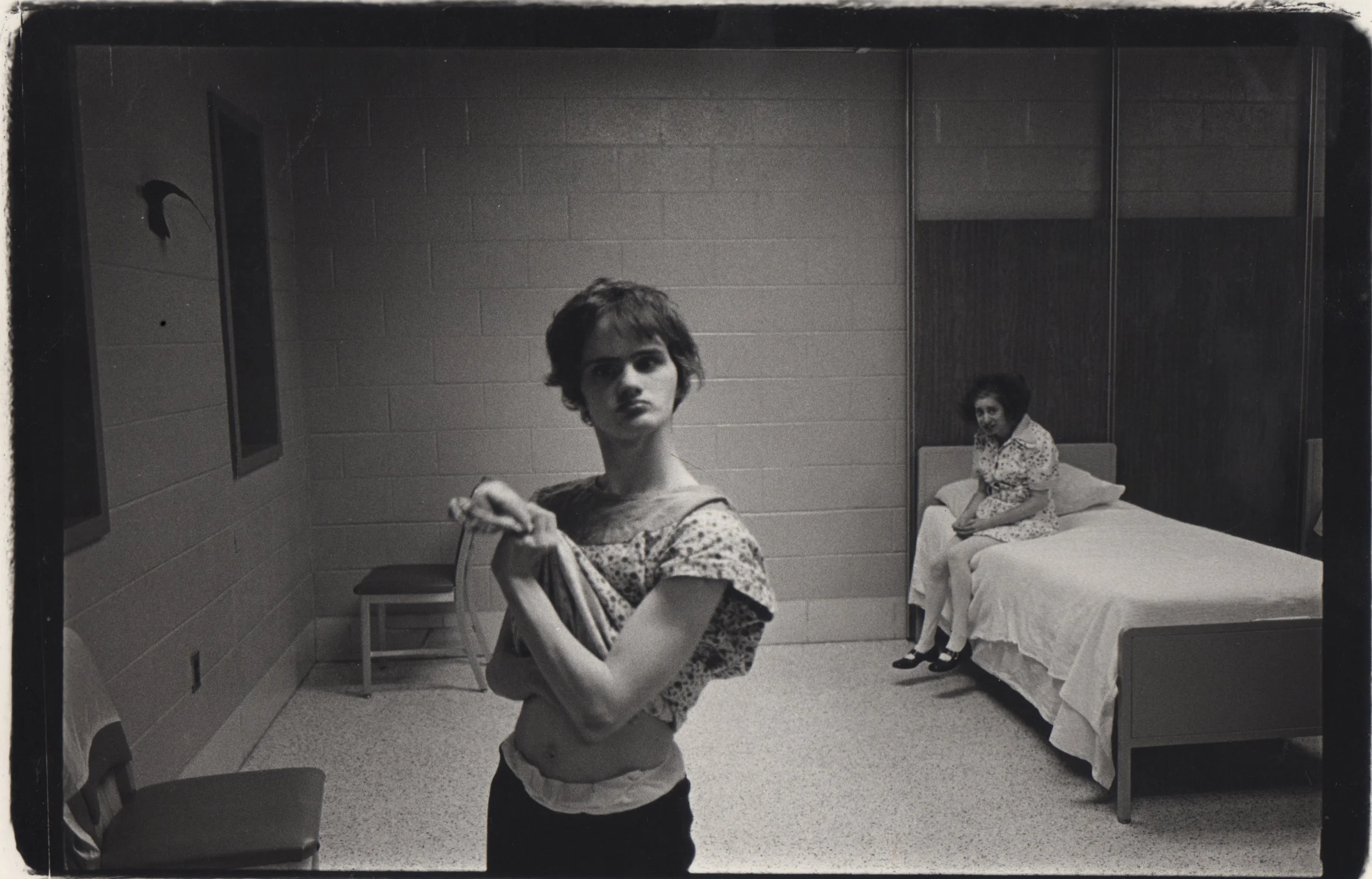

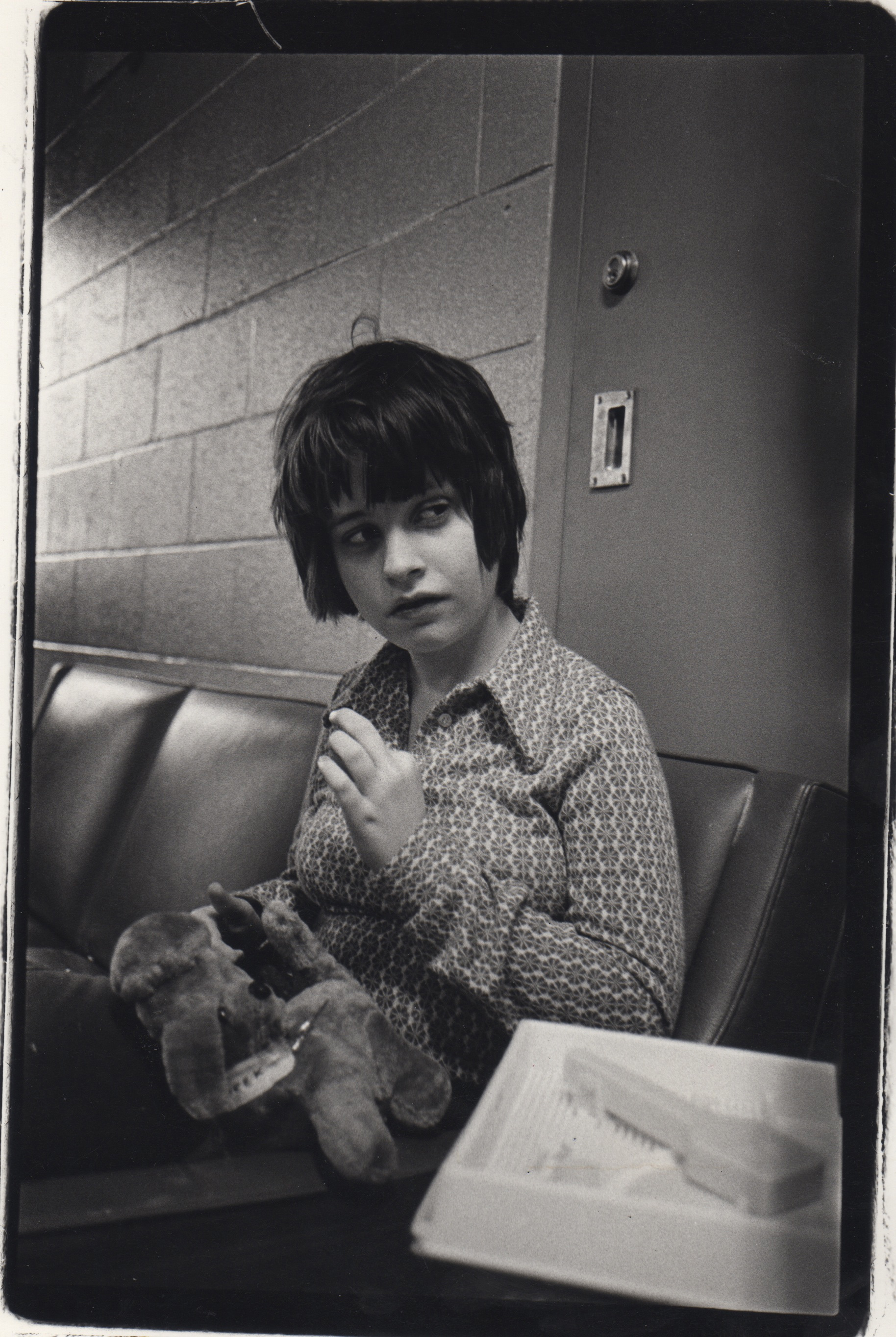

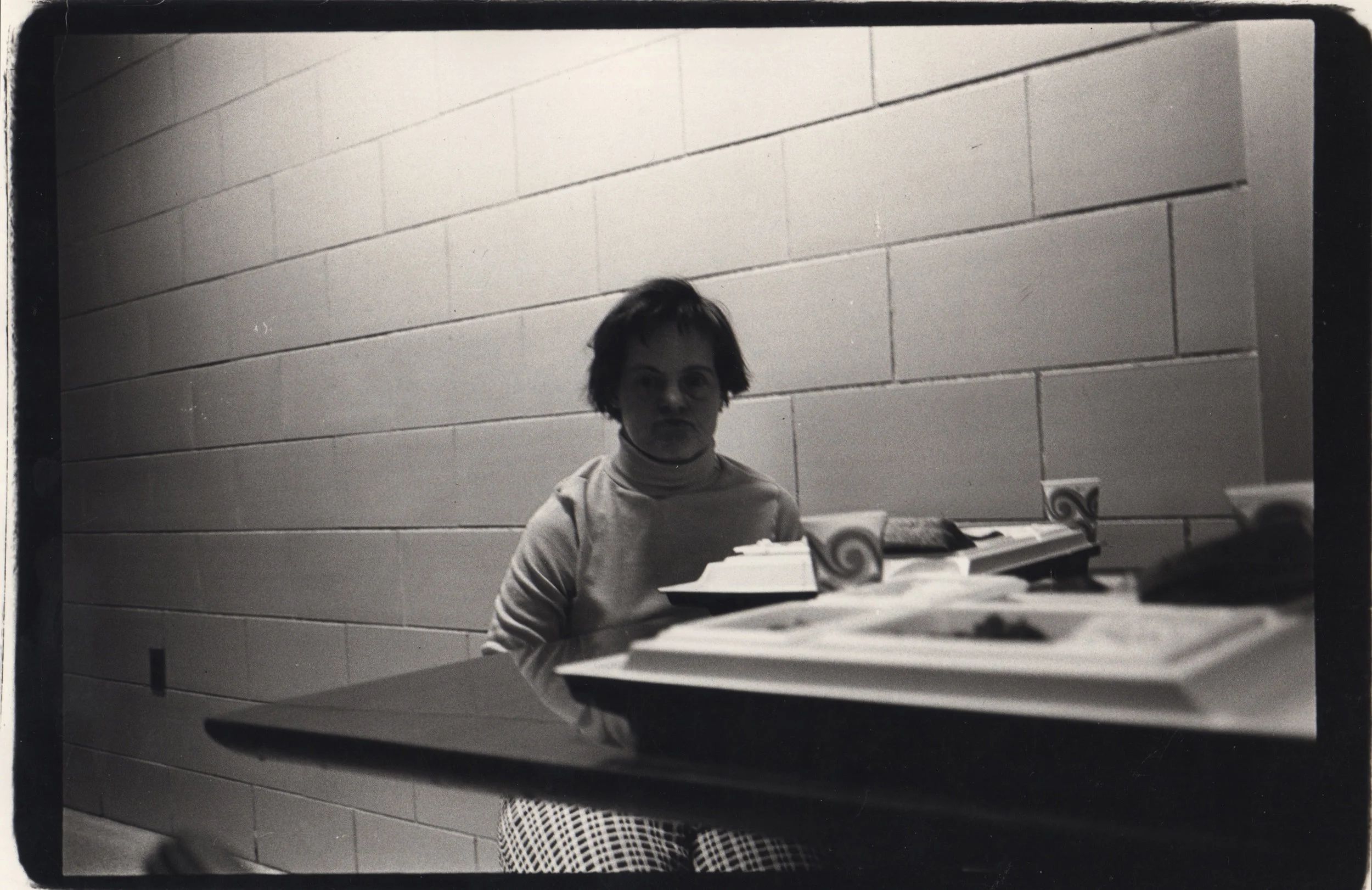

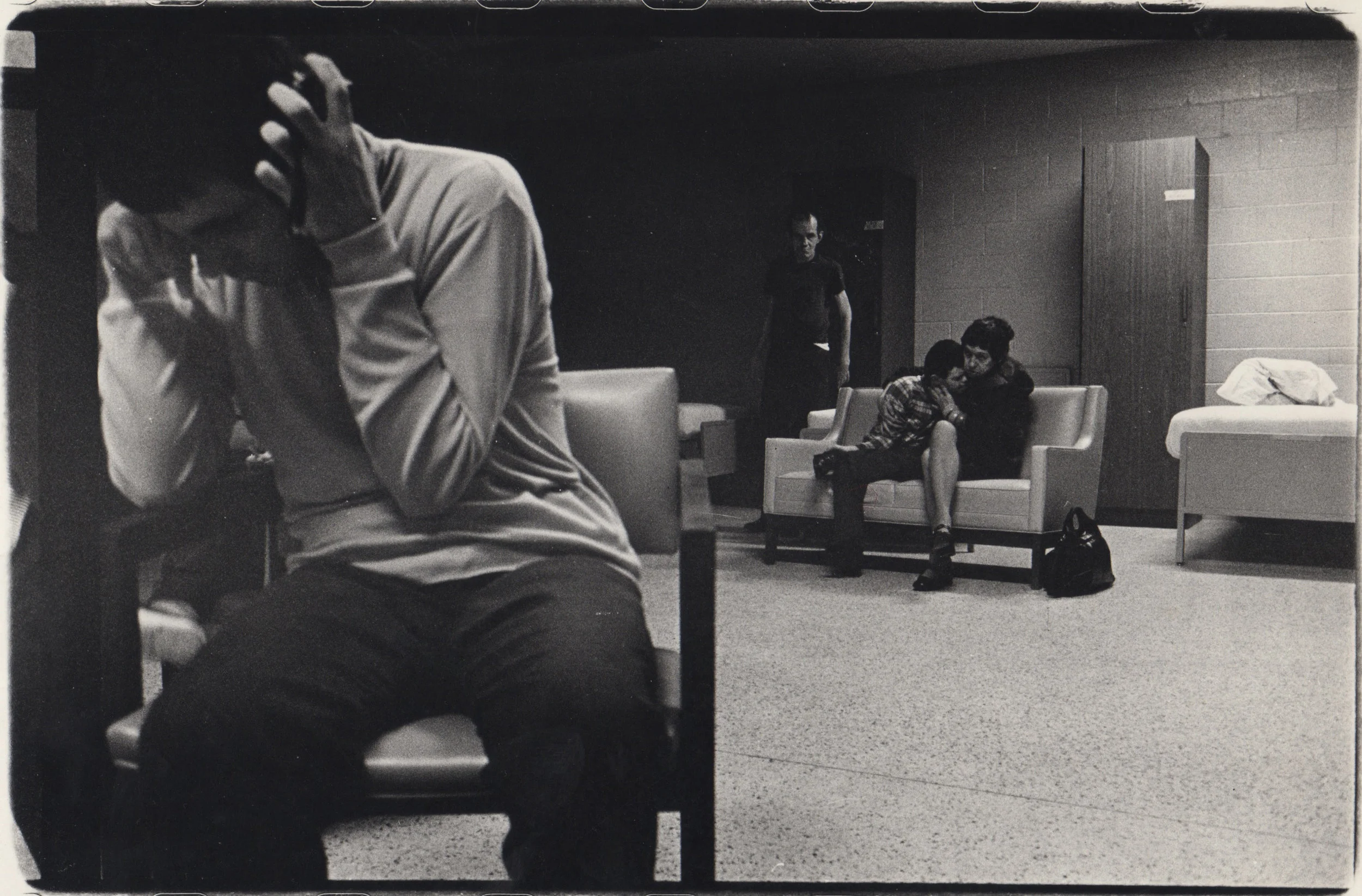

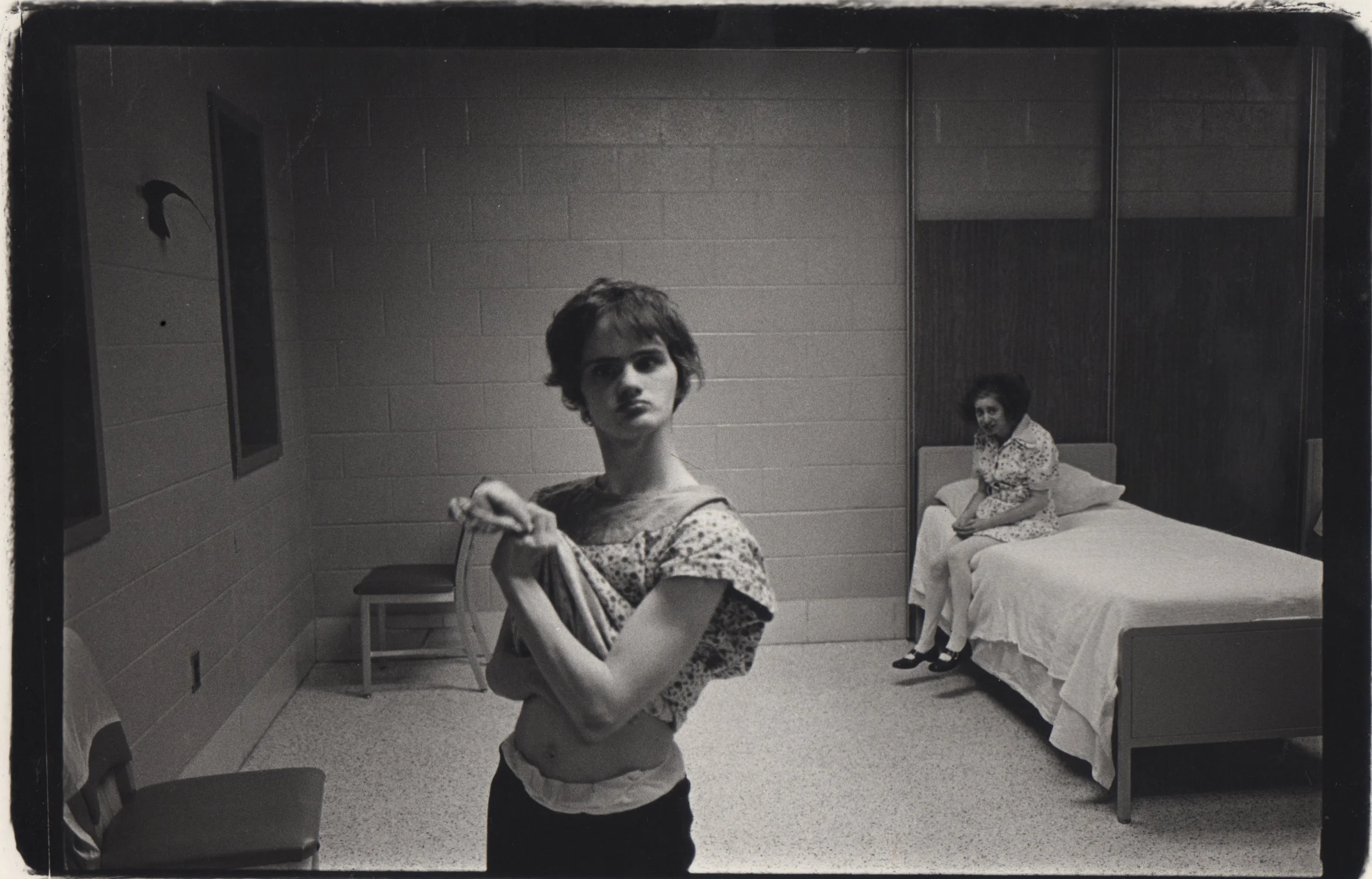

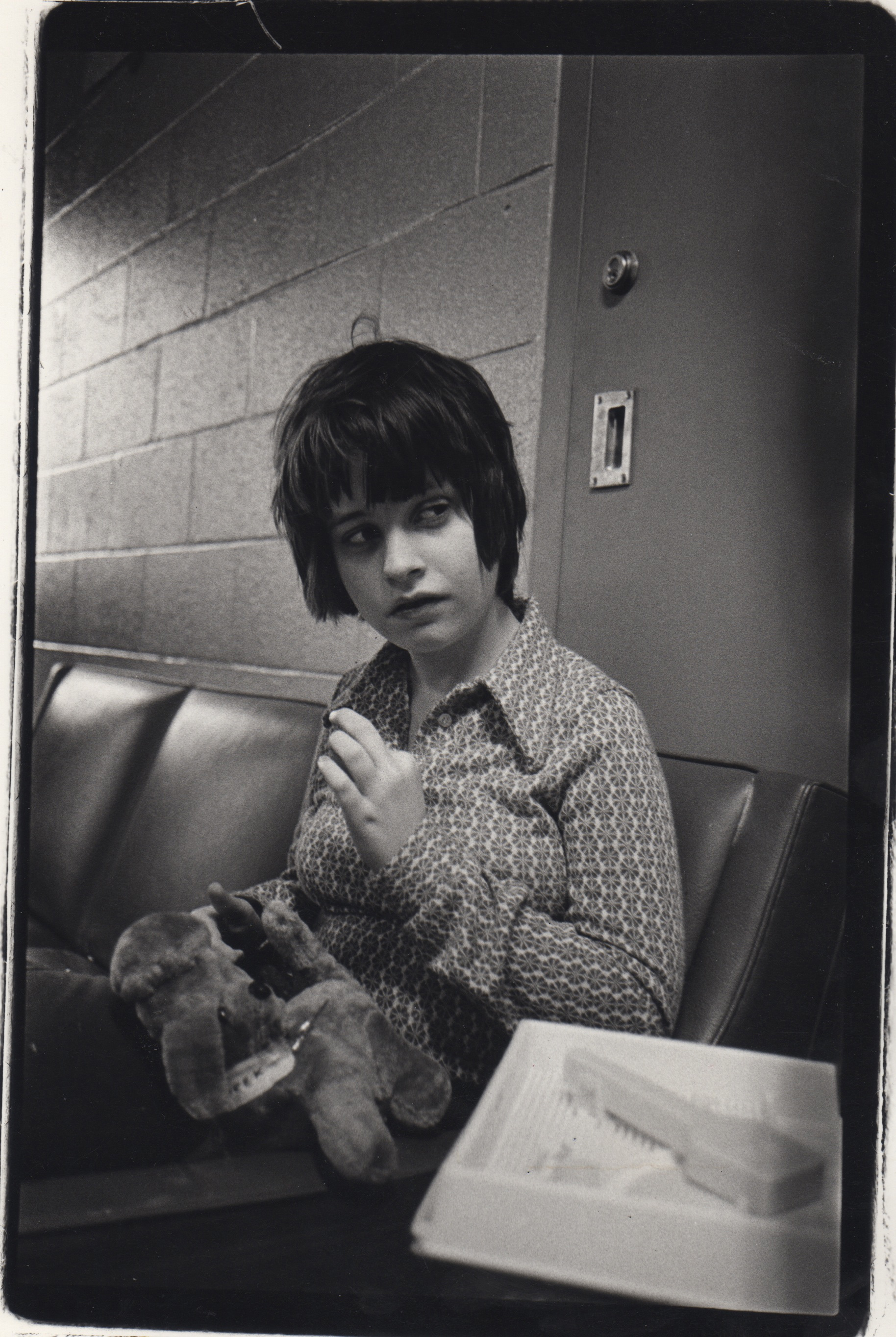

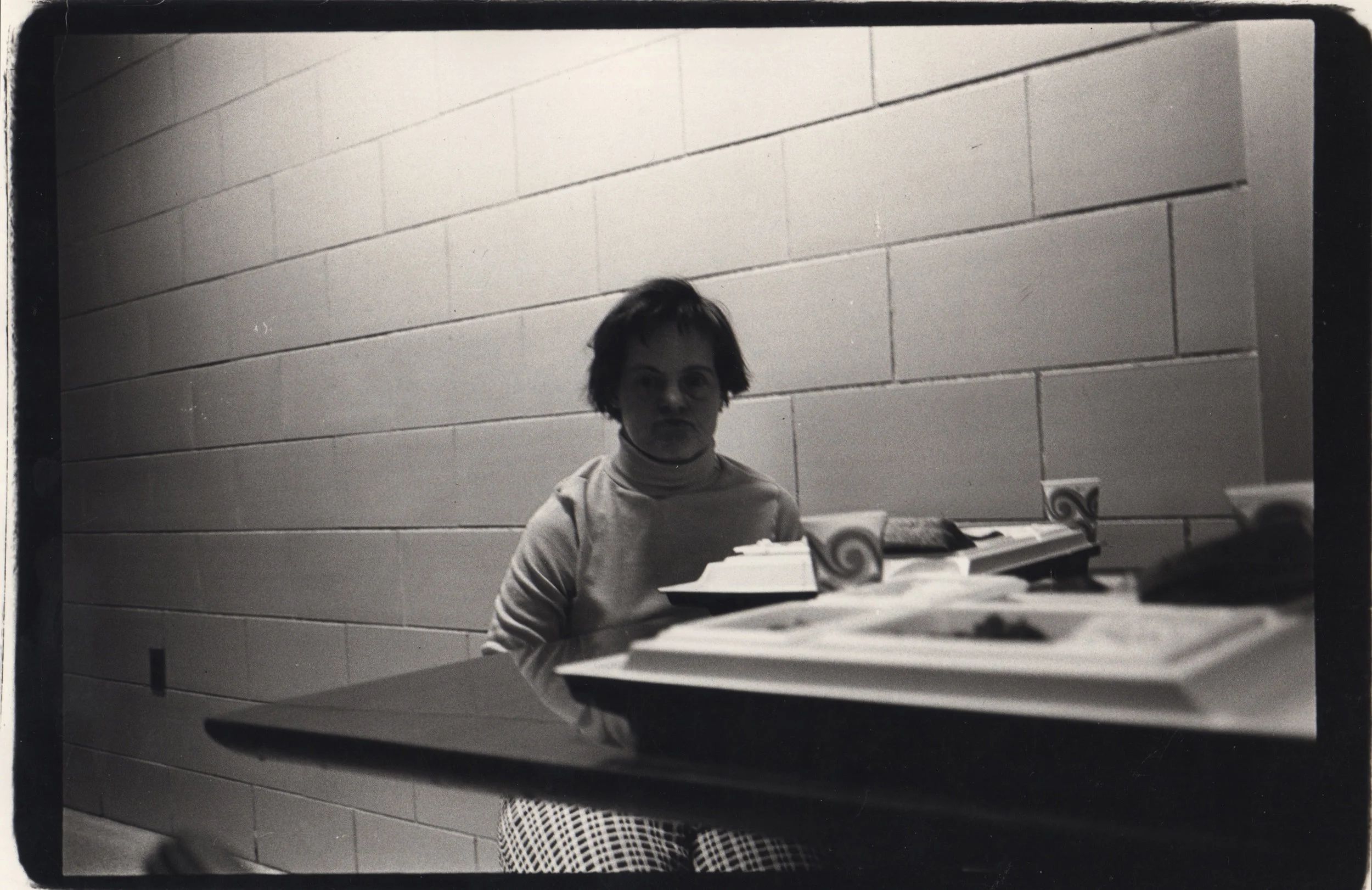

Diane Pernet is an internationally recognized dark-clad front-row face known all over the world as the brainchild behind the celebrated fashion film festival A Shaded View on Fashion (ASVOFF). But while Pernet is now widely respected as one of the key driving forces behind the fashion film genre, she has had a long, polymathic and illustrious career, working as a designer, editor, photographer, and filmmaker. In myriad forms of communication she has taken into her sway everything from the underground fashion scene bursting from the gritty streets of '80s New York, to cameo appearances in the likes of Hollywood blockbusters, such as _Prêt-à__\-Porter_. But while we could focus on many triumphs, we have chosen to turn the spotlight on her fledgling years, unearthing a truly lesser-known gemstone from her early days as a photographer. In the 1970s she created a (now sadly lost) series of portraits of mentally ill and handicapped people who were committed to an asylum in Westhaven. Only four of these photographs, which capture a netherworld of sadness and despair, remain in her possession—the rest were auctioned off with many other personal possessions left behind in a storage unit when she was a struggling artist. Here, she discusses the images and the stories behind them.

_Can you tell us a little about the genesis of these images?_ I guess I just thought it was a part of my growing process as a photographer. I'm a liberal and I love beauty, so I didn’t want to really see things that were like, you know, car crash mentality—I didn’t want to create something exploitative. It was just that my sister was working in this asylum—asylums had a really bad reputation in those days—and hearing all the stories from my sister, I thought it would be cool to take some personal pictures.

_Did this place live up to the reputation of asylums in the '70s?_ No. This place wasn’t like that at all—they treated people really well, and the social workers cared about the people inside. In order for me to have the permission to take the pictures, they asked me to make a book—sort of like portraits of the clients. I agreed, and I went up there for three months without any film in my camera, just to let them get used to me. It was quite an intense experience.

_Were there any people that really stood out for you?_ I really liked the people with Down syndrome because they were quite lovable and mischievous—they would always steal the camera, and go running down the hall. They weren’t nasty like the picture with the girl who looks like Alice in Wonderland—she was always grabbing at you; it was really quite horrible. Anyway, I got used to them for three months, and then I started taking the pictures. I would take portraits for the book and I would take pictures for myself that I knew would never be in the book, but were something that I wanted. The problem is I only have four pictures left. There was a whole series of them but I left them in a storage base, and I thought I could pay for the storage but things didn’t go the way I had expected, so they auctioned it all off—my first films, love letters from my first husband, fabric patterns, books…everything. But I had those four with me because they were my favorites. I think overall, shooting there forced me to look at things that were not so beautiful and helped me to grow—I would do something like that again if I were drawn to the subject.

_Can you tell us about the relationship between the mother and the boy in the picture in which she is sat on the bed and he is staring into camera?_ That was horrible. This woman who looks like the archetypal lovely mother kept him in a crib for 30 years, because, you know, this was the '70s, and people were embarrassed by mental illness—they would rather keep a kid in a crib, in a dark room where no one knew they existed than have people know about them, can you imagine? It’s really crazy. So, this guy couldn’t even walk at 30 years old—it was truly horrible. She would come and see him every week. Honestly, I don’t think she was a mean person. I think that she was just really ignorant.

[](#)[](#)

Shooting At The Mountains of Madness: The Lost Work of Diane Pernet

Flaunt Present Four Unearthed Photographs from the Archive of the Artistic Polymath Diane Pernet

Diane Pernet is an internationally recognized dark-clad front-row face known all over the world as the brainchild behind the celebrated fashion film festival A Shaded View on Fashion (ASVOFF). But while Pernet is now widely respected as one of the key driving forces behind the fashion film genre, she has had a long, polymathic and illustrious career, working as a designer, editor, photographer, and filmmaker. In myriad forms of communication she has taken into her sway everything from the underground fashion scene bursting from the gritty streets of '80s New York, to cameo appearances in the likes of Hollywood blockbusters, such as _Prêt-à__\-Porter_. But while we could focus on many triumphs, we have chosen to turn the spotlight on her fledgling years, unearthing a truly lesser-known gemstone from her early days as a photographer. In the 1970s she created a (now sadly lost) series of portraits of mentally ill and handicapped people who were committed to an asylum in Westhaven. Only four of these photographs, which capture a netherworld of sadness and despair, remain in her possession—the rest were auctioned off with many other personal possessions left behind in a storage unit when she was a struggling artist. Here, she discusses the images and the stories behind them.

_Can you tell us a little about the genesis of these images?_ I guess I just thought it was a part of my growing process as a photographer. I'm a liberal and I love beauty, so I didn’t want to really see things that were like, you know, car crash mentality—I didn’t want to create something exploitative. It was just that my sister was working in this asylum—asylums had a really bad reputation in those days—and hearing all the stories from my sister, I thought it would be cool to take some personal pictures.

_Did this place live up to the reputation of asylums in the '70s?_ No. This place wasn’t like that at all—they treated people really well, and the social workers cared about the people inside. In order for me to have the permission to take the pictures, they asked me to make a book—sort of like portraits of the clients. I agreed, and I went up there for three months without any film in my camera, just to let them get used to me. It was quite an intense experience.

_Were there any people that really stood out for you?_ I really liked the people with Down syndrome because they were quite lovable and mischievous—they would always steal the camera, and go running down the hall. They weren’t nasty like the picture with the girl who looks like Alice in Wonderland—she was always grabbing at you; it was really quite horrible. Anyway, I got used to them for three months, and then I started taking the pictures. I would take portraits for the book and I would take pictures for myself that I knew would never be in the book, but were something that I wanted. The problem is I only have four pictures left. There was a whole series of them but I left them in a storage base, and I thought I could pay for the storage but things didn’t go the way I had expected, so they auctioned it all off—my first films, love letters from my first husband, fabric patterns, books…everything. But I had those four with me because they were my favorites. I think overall, shooting there forced me to look at things that were not so beautiful and helped me to grow—I would do something like that again if I were drawn to the subject.

_Can you tell us about the relationship between the mother and the boy in the picture in which she is sat on the bed and he is staring into camera?_ That was horrible. This woman who looks like the archetypal lovely mother kept him in a crib for 30 years, because, you know, this was the '70s, and people were embarrassed by mental illness—they would rather keep a kid in a crib, in a dark room where no one knew they existed than have people know about them, can you imagine? It’s really crazy. So, this guy couldn’t even walk at 30 years old—it was truly horrible. She would come and see him every week. Honestly, I don’t think she was a mean person. I think that she was just really ignorant.

[](#)[](#)

Shooting At The Mountains of Madness: The Lost Work of Diane Pernet

Flaunt Present Four Unearthed Photographs from the Archive of the Artistic Polymath Diane Pernet

Diane Pernet is an internationally recognized dark-clad front-row face known all over the world as the brainchild behind the celebrated fashion film festival A Shaded View on Fashion (ASVOFF). But while Pernet is now widely respected as one of the key driving forces behind the fashion film genre, she has had a long, polymathic and illustrious career, working as a designer, editor, photographer, and filmmaker. In myriad forms of communication she has taken into her sway everything from the underground fashion scene bursting from the gritty streets of '80s New York, to cameo appearances in the likes of Hollywood blockbusters, such as _Prêt-à__\-Porter_. But while we could focus on many triumphs, we have chosen to turn the spotlight on her fledgling years, unearthing a truly lesser-known gemstone from her early days as a photographer. In the 1970s she created a (now sadly lost) series of portraits of mentally ill and handicapped people who were committed to an asylum in Westhaven. Only four of these photographs, which capture a netherworld of sadness and despair, remain in her possession—the rest were auctioned off with many other personal possessions left behind in a storage unit when she was a struggling artist. Here, she discusses the images and the stories behind them.

_Can you tell us a little about the genesis of these images?_ I guess I just thought it was a part of my growing process as a photographer. I'm a liberal and I love beauty, so I didn’t want to really see things that were like, you know, car crash mentality—I didn’t want to create something exploitative. It was just that my sister was working in this asylum—asylums had a really bad reputation in those days—and hearing all the stories from my sister, I thought it would be cool to take some personal pictures.

_Did this place live up to the reputation of asylums in the '70s?_ No. This place wasn’t like that at all—they treated people really well, and the social workers cared about the people inside. In order for me to have the permission to take the pictures, they asked me to make a book—sort of like portraits of the clients. I agreed, and I went up there for three months without any film in my camera, just to let them get used to me. It was quite an intense experience.

_Were there any people that really stood out for you?_ I really liked the people with Down syndrome because they were quite lovable and mischievous—they would always steal the camera, and go running down the hall. They weren’t nasty like the picture with the girl who looks like Alice in Wonderland—she was always grabbing at you; it was really quite horrible. Anyway, I got used to them for three months, and then I started taking the pictures. I would take portraits for the book and I would take pictures for myself that I knew would never be in the book, but were something that I wanted. The problem is I only have four pictures left. There was a whole series of them but I left them in a storage base, and I thought I could pay for the storage but things didn’t go the way I had expected, so they auctioned it all off—my first films, love letters from my first husband, fabric patterns, books…everything. But I had those four with me because they were my favorites. I think overall, shooting there forced me to look at things that were not so beautiful and helped me to grow—I would do something like that again if I were drawn to the subject.

_Can you tell us about the relationship between the mother and the boy in the picture in which she is sat on the bed and he is staring into camera?_ That was horrible. This woman who looks like the archetypal lovely mother kept him in a crib for 30 years, because, you know, this was the '70s, and people were embarrassed by mental illness—they would rather keep a kid in a crib, in a dark room where no one knew they existed than have people know about them, can you imagine? It’s really crazy. So, this guy couldn’t even walk at 30 years old—it was truly horrible. She would come and see him every week. Honestly, I don’t think she was a mean person. I think that she was just really ignorant.