Exhibition View of Paradies Amerika, (2014). Courtesy the Artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

Exhibition View of Paradies Amerika, (2014). Courtesy the Artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

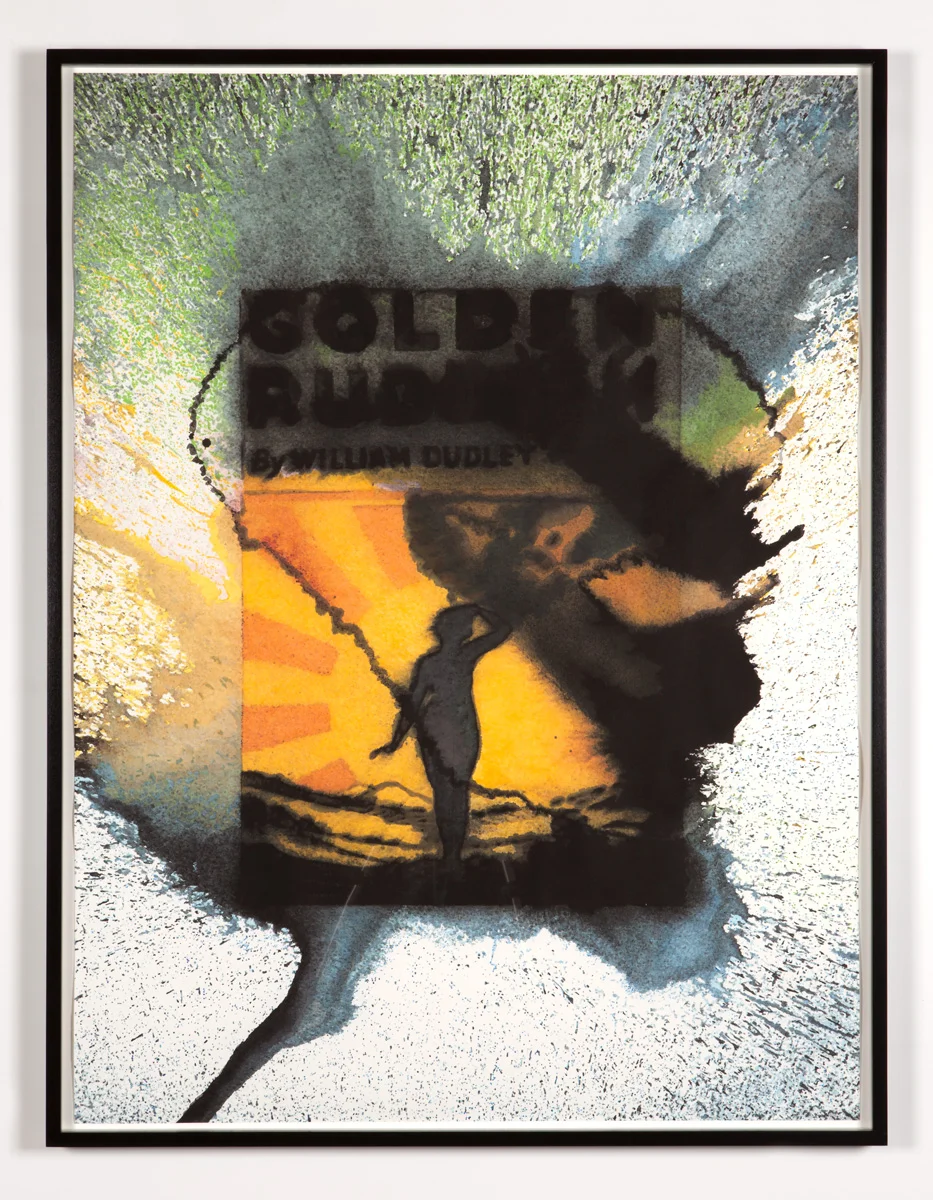

“Pacific Palisades (Golden Rubbish #1),” (2015). Solvent and water-based ink on Arches. 53 x 42 inches. Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

Exhibition View of Paradies Amerika, (2014). Courtesy the Artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

“Study #1 for Paradies Amerika (Invocation of the Pleasuredome/Beach Party),” (2015). Solvent and water-based ink on Arches, polyester resin on wood. 9 9/16 x 12 inches. Courtesy the artist and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles.

[](#)[](#)

Drew Heitzler

Your Propaganda is an All-Inclusive Lifestyle

I’m sitting in my car waiting for Drew Heitzler. I’m outside the Mandrake—the bar that the Los Angeles-based artist is a co-owner of—as I wait, I look in the rearview mirror and am shocked to see a woman in a wedding dress, a man in a tuxedo, and two photographers standing in the middle of the road taking pictures. I look in the opposite direction; this winding stretch of La Cienega is shuttered on a Sunday; the smog hangs low and the sills of the galleries are covered with a fine dusting of particulate matter bearing witness to the logjam traffic that consumes this street the majority of the time.

Heitzler is a tall man in his forties with a shaved head and large-frame glasses—a Gen-X’er who has accepted the passing of time, but not succumbed to it. We start discussing conspiracy theorists and paranoia; both are themes in his 2014 show at Blum & Poe, Paradies Amerika—based on the work of Austrian and Czechoslovak reporter Egon Erwin Kisch. In the 1920s Kisch visited the United States—California in particular—and wrote a scathing review of the country in his native German tongue, it has yet to be translated.

“California has this darkness,” Heitzler says, “the propaganda is that it’s this sunny, beautiful place, but there’s all this nice murky stuff that rests underneath, and that’s the stuff that I think is interesting.”

Heitzler is an avid researcher and specializes in combining sources that have no apparent correlation, but when put in proximity reveal a common truth. An example is the 2011 video installation “Spiral Jetty / Crystal Voyager / Région Centrale (Bootlegged, Re-ordered, Combined, Sometimes More, Sometimes Less),” which shows selections from three films side-by-side: _Spiral_ _Jetty_ (1970) by land artist Robert Smithson, _Crystal_ _Voyager_ (1973) by California surf filmmaker George Greenough, and Canadian experimental film _La_ _Région_ _Centrale_ (1970) by Michael Snow. The disparate films, through Heitzler’s editing reveal an unexpected synergy; at one point the three screens show, respectively, an X, where the reel has either ended or not yet begun, dust churning behind an automobile, and a Do Not Enter Sign; each part illuminating the whole.

Heitzler was born in Charleston, South Carolina and schooled in New York City and London before moving West a decade ago. He sees himself as a demythologizer of the California story, “I came to \[Los Angeles\] with these preconceived notions of what it was, and then got here and I lived on Comey Avenue, and I would drive down La Cienega to go to the Home Depot, and go through the oil fields down there. That just blew my mind that there were oil fields in the middle of the city. I was poking around into the history of the place, and I found that while Hollywood is a part of the industry, it’s not even most of it, you have oil and aerospace, there are huge military operations here. It occurred to me, L.A. has this huge industry, but no one ever pays attention to it, because the Hollywood gloss coat disguises it all. Then I realized that that is what film noir is about.”

Themes of objectivism and subjectivism run through Heitzler’s work. Pieces like “Drawing for Pacific Palisades,” read like a conspiracy theorist’s’ mind map, connecting Aldous Huxley and the Doors, Taylor Swift, and Stevie Nicks.

“I don’t vet my material very well,” Heitzler explains, “So in some cases my research will be peer-reviewed MIT press, but in other cases it will be online rants about UFOs, and I lend the same weight to all the material that I read.

“In the old days,” Heitzler continues, “a \[world\] event would happen, and reporters would descend on it, and they would all go around, and they would get their information, and they would hang around the hotel bar that night where they were staying, and through that conversation, they would come to some sort of consensus about what had happened. So amongst the news outlets of the world, you had this consistent idea of what happened.”

“Now,” he says, “you have more access to the truth, because there’s so much information, but I don’t necessarily think that’s true, because when you’re bombarded with that much information and opinion, there’s no formation of consensus, or that consensus happens over a much longer period of time, and while that is happening, some other event happens, and the first one is forgotten.”

The sun is dipping over the Pacific by the time I leave the Mandrake. Blood orange rays pierce the smog in a deceptively lovely display of the destruction humans have bestowed on our environment. The newlyweds and the photographers are long gone, leaving halos of matrimonial ignorance in the dust. The Westside can sometimes feel like stepping into someone’s idea of what this city should be. Heitzler, it seems, is doing his best to lift the veil on that façade.