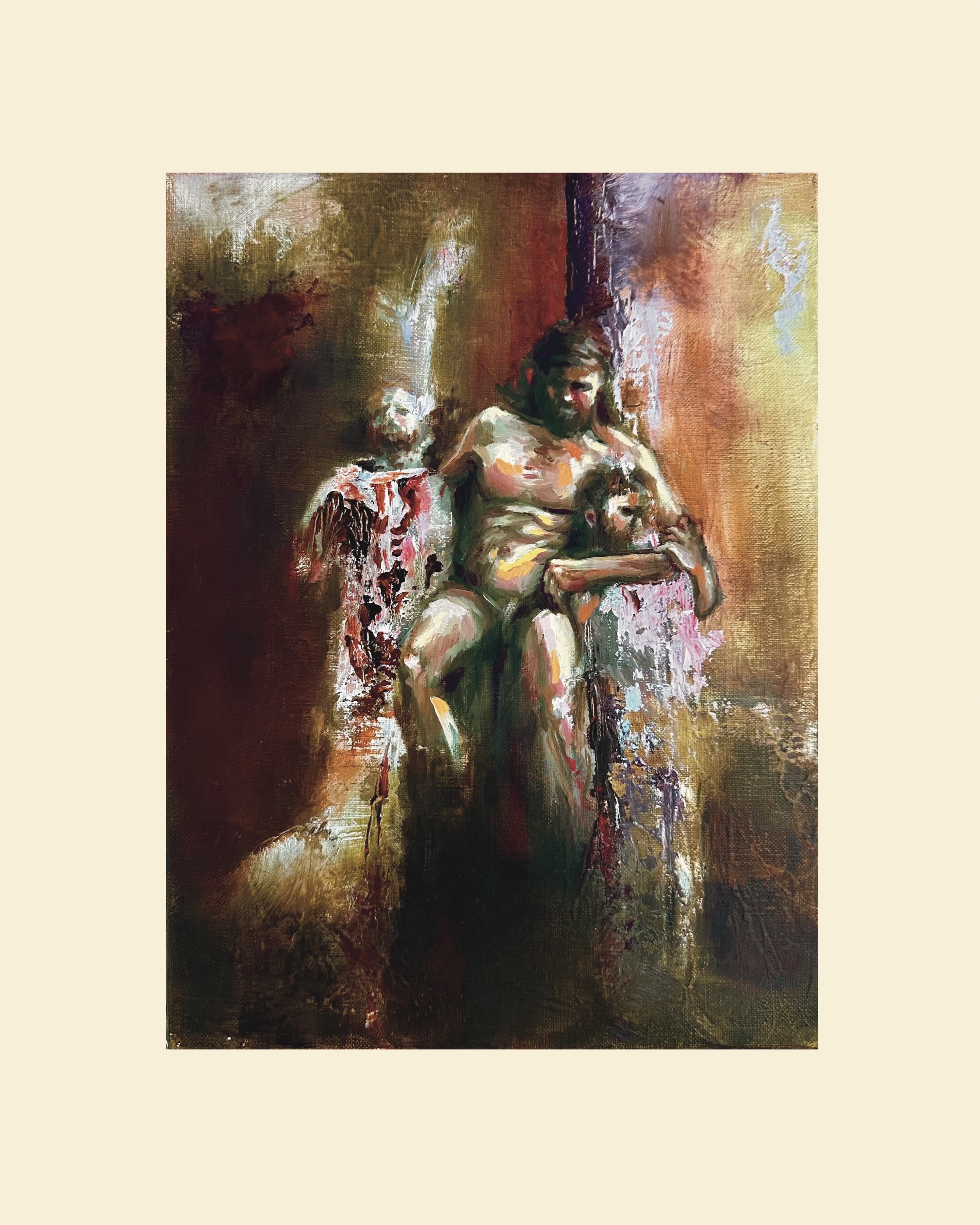

“Say what you see,” encourages artist Egan Frantz, but do so cautiously. See, when exactingly stringing new language theorems about a gallery space via the metaphysics of objects in beautiful stasis, or repetition—in this case erect baguettes, say, or previously drunk, bucket-submerged bottles of Champers—remember this: “In discourse, we must be like vipers.” So Frantz shares regards verbal dissection of his creations, while pacing his latest installation at Culver City’s Roberts & Tilton gallery, amidst the constant sound of bubbles his cuvees send surface-ward. His position is indeed a viperous one—the works, in their thoughtful serialization, develop a kind of rigorous, exploratory ethics, a language in and of themselves. That Frantz is handsome and stylish and opinionated and young and sharp-tongued makes this language construction, what he dubs “ethical audacity” in a nod to Roland Barthes, glimmer with arty appeal. But there’s a softness, too, a simplistic openness in the work, that encourages unencumbered enjoyment of its construction, perhaps even sentimentally so, as the onomatopoeic bubbling throughout the room reminds one of the bathtub, rainwater exceeding a bucket placed for collection, or a well-wishing fountain perhaps. Frantz accommodates, sweetly: “With discourse, venom, yes, but with friends and family, you gotta be sweet.”

Days later, following news that Frantz has been selected for the Statements section of next summer’s Art Basel, Switzerland, we’re making like friends, talking Lacanian penopticons over a bottle of California burgundy courtesy a West Hollywood hotel lobby. “I reject the idea that language can truly communicate,” Frantz says, in light of the challenges his installation, in its orchestral, idiomatic role playing, faces. “There isn’t a genre for this work, I don’t think, yet. The closest thing would be the writers’ and philosophers’ ‘speculative realism’ [preferring realism to idealism, more or less]. I align with notions that replace post-Kantian finality with chance and contingency.” Frantz substantiates this with his position on object potentiality, but also the nature of the artist as object. “Consider a vase,” he says, “Whether you put flowers in it or not, it’s not going to become a unicorn, right? Still, whether you use it, or you theorize it, you haven’t exhausted it. The thing itself has its own kind of agency, and in a sense, we are at the mercy of it as this kind of anonymous material. And there’s a disconnect, I think, where the viewer qualifies the work on just some fucked up level of ‘this is boring’ or ‘this is too crazy.’ But to be an analyst, you have to be analyzed. And I think we as artists are subjects to analysts who haven’t been analyzed—the artist becomes a patient.”

While Frantz eagerly espouses the successes of the long dead philosophers and writers he admires, he is quick to dismiss their authorial license in his work, flirting instead with the philosophical zeitgeist and calculatedly breaking rules after knowing them. “For me,” he concludes, “I treat theory and practice equally … and one might look at the work and call it ‘conceptual,’ but to that I disagree—in fact it’s very obvious, and political. There are many artists who are not making culture, but who are entertaining culture. And that’s fine. But for me, and my trajectory, there’s a very formal process.”

Written by Matthew Bedard

F L A U N T

.JPG)

.jpg)