My brother, Will, lives in Cyprus, and the one thing I think we can all take away from his experience there is the simple truth that none of us know where Cyprus is. I think of it akin to finding out that someone you’ve just met on the street grew up next door, or had the same piano teacher as you, or dated

the same guy you did in high school—bonded but distant; shared but unknown. The reason I know that none of us (or you, rather) could find Cyprus on a map is because the exact same expression creeps across the face of everyone I’ve told this to so far—about thirty people in the last four months.

It’s fascinating really, as if they all got together and decided that this was the only appropriate reaction to the statement: “My brother, Will, lives in Cyprus”. The unmistakable countenance appears as they try to place where the fuck Cyprus is on their mental map (and no, not the one in Orange County, that’s Cypress, like the tree). It’s the look you get when you stumble out of an afternoon matinee and realize it’s only 4:00 PM and still quite sunny outside. It’s the squint, as you try and reconcile the preternaturally bright day with your warped perception of time. It’s the head cocked to the side, as if looking at the sun from a slant will make it all make more sense.

I realized some time ago that I should not wait for this look to fade into any sort of correct understanding of where (or what for that matter) Cyprus is.

My answer, which I have repeated word for word each time I’ve seen this expression, is: “Yeah, it’s that island kinda between Turkey and Egypt in the Mediterranean Sea. It’s a sovereign state but half of it is run by the Greeks and the other half by the Turks cuz of some political thing in the ’60s. It’s wild but yeah, that’s where he lives.” The one person I’ve read this cue card to who actually knew the history of the island corrected me that, actually, Cyprus was bifurcated in 1974, not “in the ’60s” but I didn’t change my answer, and it hasn’t really mattered.

I bring Will up because with the ten-hour time difference between San Francisco and his temporary island home our primary form of communication is him sending me articles related to his research and me sending him memes related to nothing. For the past four and next five months he was and will continue to be marooned, in order to complete his Fulbright research scholarship in art. He’s creating work (sculpture, photography, film) and writing theory on artifact restoration as a metaphor for political reconciliation. (It’s okay—I don’t understand it either—just keep reading, that’s not what this is about anyway.)

As he travels daily between Greek- and Turkish-controlled Cyprus, traversing across a line in the sand, he Whatsapps me journal articles and critical art theory. In lieu of telling me what he’s actually doing or writing or making art about, I’m left to distill his physical and mental locations from the content of his daily cannon. And it seems, even on an island in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, he can’t help but think about the political division we mainlanders are reading about and living in and desperately trying to mend. Recently, he sent along an article by the postmodern non-rationalist political theorist Chantal Mouffe discussing this exactly and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since.

Open up a newspaper—just kidding, no one’s done that in years, open up _The New York Times_ app—and you’re greeted with one of two kinds of stories. I bet you ten-to-one the headlines will either read “Look at what _they_ did! Isn’t that terrible? Why did they do that?”, or “Look at what _we_ did! Aren’t we great! Finally, we’re winning again.” Stories on political and ideological difference have become trope-ish and banal in their repetition such that being divided _feels_like the true state of our country. Following this directly, trouncing, slandering, and personally and politically defiling our opponents _feels_ like the only way we can return to democracy and decorum after coming this far down the road. After all, one side has to win, right?

If we can though, let’s digress from this dichotomous assumption. What if there was another path to democracy, or another form of democracy altogether separate from the construct of a winner and a loser? Compromise and understanding feel like distant and entirely unachievable options at this point—but maybe we’re just not thinking about them in quite the right way.

The foundation of Mouffe’s argument requires defining two very similar but unique forms of democratic thought: antagonistic democracy as opposed to agonistic democracy. Mouffe refers to the type of democracy comprised of an enemy and adversary as “antagonistic democracy”—this is the democracy you read about every day. In her own words, antagonistic democracy attempts to “constitute a ‘we’, and distinguish it from a ‘they’. Consequently, the crucial question of democratic politics is not to reach a consensus without exclusion which would amount to creating a ‘we’ without a corollary ‘they’ but to manage to establish the we/they discrimination...”

The theory of antagonistic democracy recognizes that “we live in a world where a multiplicity of perspectives and values coexist and, for reasons it believes to be empirical, accepts that it is impossible for each of us to adopt them all. But it imagines that these perspectives and values, brought together, constitute a harmonious and non-conflictual ensemble.” In reality though, this is a fallacy Mouffe says—the ensemble can’t exist. There is no room for harmony after you’ve called your political rival an idiot and a criminal.

Antagonistic democracy necessitates exclusion by way of inclusion. By defining yourself as ‘liberal’ and including certain people in your group, you must necessarily exclude others (conservatives, but also others who fall somewhere else on the spectrum). Yet at the same time, a democracy like this is expected to result in outcomes and rules that all citizens must live peacefully under. Mouffe sees this as absurd: how can we expect compromise and understanding when the foundation of the political bodies is based on excluding people and ideas they fundamentally disagree with?

Her answer to antagonistic democracy and its shortcomings is agonistic democracy. Where antagonistic democracy necessitates a construct of friend/enemy, agonistic democracy exists in the space of the _relationship_ between adversaries. Agonistic democracy is the “distinction between the categories of enemy and adversary...meaning that within the ‘we’ that constitutes the political community, the opponent is not considered an enemy to be destroyed but an adversary whose existence is legitimate. His ideas will be fought with vigour but his right to defend them will never be questioned.” Whereas antagonistic democracy leaves no room for real compromise, agonistic democracy, in its definition of struggle and the real possibility for compromise by avoiding exclusionary/ inclusionary logic, represents a truer form of democracy.

Samuel Chambers, another political theorist, summarizes Mouffe’s argument on the subtle but crucial difference between antagonistic and agonistic democracies well. He writes that “Agonism implies a deep respect and concern for the other; indeed, the Greek _agon_ refers most directly to an athletic contest oriented not merely toward victory or defeat, but emphasizing the importance of the struggle itself—a struggle that cannot exist without the opponent. Victory through forfeit or default, or over an unworthy opponent, comes up short compared to a defeat at the hands of a worthy opponent—a defeat that still brings honor. An agonistic discourse will therefore be one marked not merely by conflict but just as importantly, by mutual admiration...”

The goal of our democracy then should not be to bring two opposing sides together to create consensus through a no-matter-what-I-am-right philosophy, because that’s not how compromise works. We shouldn’t actually be striving for harmony, whether through defeat or compromise.

In actuality, the job of a democracy is to “provide the arena” for conflict and set the ground rules for that conflict, so when enemy and adversary leave the ring, even though one may be victorious, the other is still valid and both sides are able to accept the social, judicial, and political outcomes. Struggle is key to any democracy. When the struggle is over though, we must still be able to recognize our adversaries as valid and respectable. It is in this small space that the compromise and harmony we seek—and true democracy—exists. This arena, these ground rules, are precisely what we have lost in America in the last few years. And I would argue that their loss is what makes all of this feel so dreadful and hopeless so often, for it’s a terrifying thought to think that we’ve lost a fundamental part of our democracy.

I must admit that while Mouffe’s argument is a nice ideal, I have a hard time seeing it play out anytime soon. When the political becomes personal and we begin fighting ideological and social battles through personal attacks, we have failed to be democratic. The question is: at what point down the road of libel and slander can we no longer return to the crossroads of democracy? How many times do you have to scream “Lock Her Up!” or “Impeach the Orange!” before it’s impossible to step back into the arena of decency?

I’ve been thinking about Mouffe and her argument for weeks now hoping that focusing on what she believes to be the truth of democracy I could gain some insight as to how we can actually achieve this in our current political climate. Unfortunately, just having the language and constructs of what an ideal democracy should look like does not an ideal democracy make.

I knew my brother would have plenty of thoughts on the matter, and wanted to know if he had any answers for me. After all, he’s where all of this started. I wanted to know what he, living on an island that is literally divided in two, made of agonistic democracy. I wanted to know if the Cypriots had found a way to make it work. As I left work around 6:00 PM San Francisco time, I called him. The phone rang for a few moments before I realized my mistake. It was 4:00 AM in Cyprus, and he was asleep.

As I walked home in the drizzle and fog, up the hill to my apartment, and my cat, and a warm shower my thoughts on the matter relented a bit. And now, as I write this, I can just only say that this is where hope comes in. This is where hope that we can learn to fight not to destroy and exclude those that are different, but rather that we can fight and at the end of it all, look across the aisle and see ourselves.

_Written by_ **Charlie Wiebe**

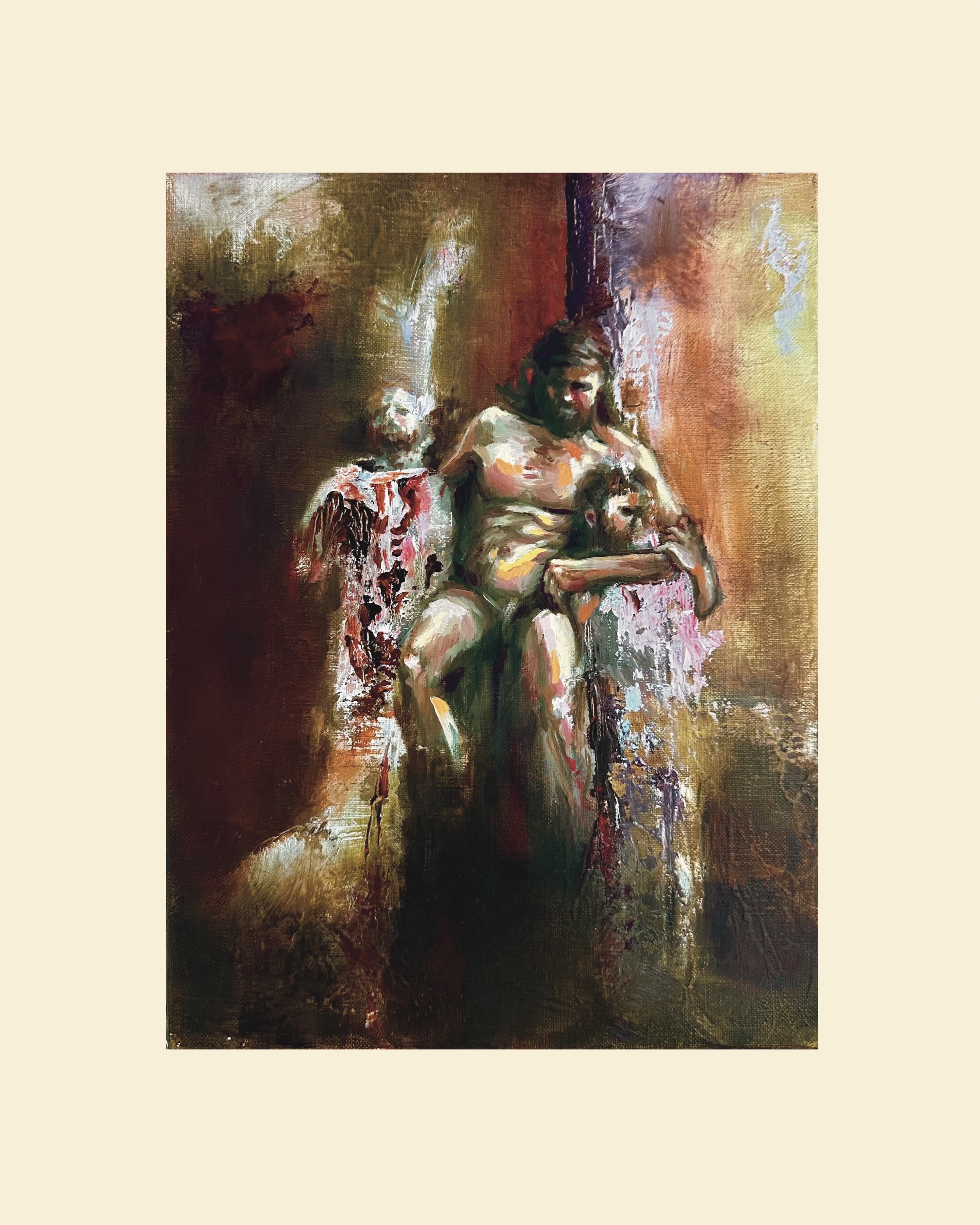

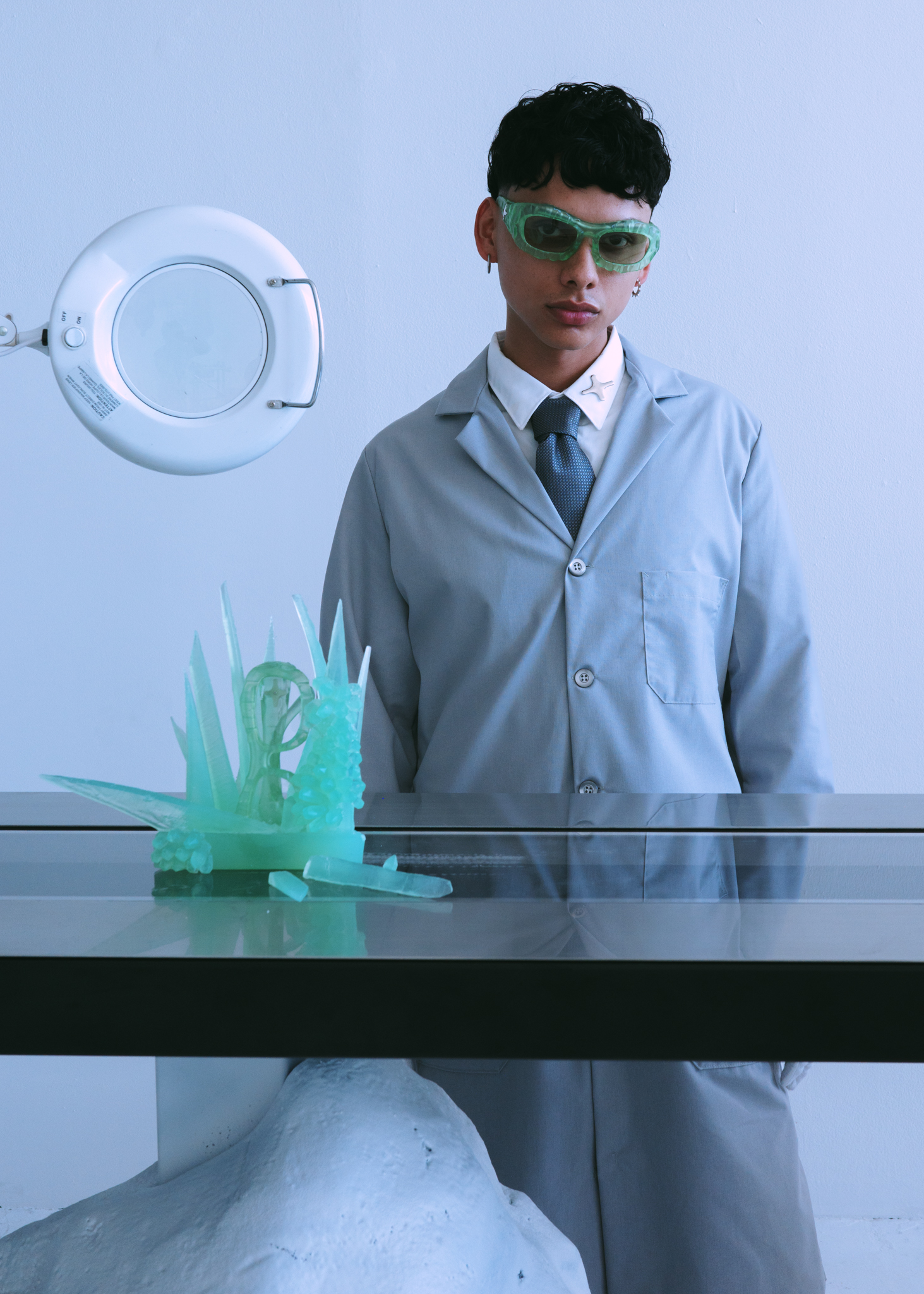

_Illustrations by_ **Daryn Ray**

My brother, Will, lives in Cyprus, and the one thing I think we can all take away from his experience there is the simple truth that none of us know where Cyprus is. I think of it akin to finding out that someone you’ve just met on the street grew up next door, or had the same piano teacher as you, or dated

the same guy you did in high school—bonded but distant; shared but unknown. The reason I know that none of us (or you, rather) could find Cyprus on a map is because the exact same expression creeps across the face of everyone I’ve told this to so far—about thirty people in the last four months.

It’s fascinating really, as if they all got together and decided that this was the only appropriate reaction to the statement: “My brother, Will, lives in Cyprus”. The unmistakable countenance appears as they try to place where the fuck Cyprus is on their mental map (and no, not the one in Orange County, that’s Cypress, like the tree). It’s the look you get when you stumble out of an afternoon matinee and realize it’s only 4:00 PM and still quite sunny outside. It’s the squint, as you try and reconcile the preternaturally bright day with your warped perception of time. It’s the head cocked to the side, as if looking at the sun from a slant will make it all make more sense.

I realized some time ago that I should not wait for this look to fade into any sort of correct understanding of where (or what for that matter) Cyprus is.

My answer, which I have repeated word for word each time I’ve seen this expression, is: “Yeah, it’s that island kinda between Turkey and Egypt in the Mediterranean Sea. It’s a sovereign state but half of it is run by the Greeks and the other half by the Turks cuz of some political thing in the ’60s. It’s wild but yeah, that’s where he lives.” The one person I’ve read this cue card to who actually knew the history of the island corrected me that, actually, Cyprus was bifurcated in 1974, not “in the ’60s” but I didn’t change my answer, and it hasn’t really mattered.

I bring Will up because with the ten-hour time difference between San Francisco and his temporary island home our primary form of communication is him sending me articles related to his research and me sending him memes related to nothing. For the past four and next five months he was and will continue to be marooned, in order to complete his Fulbright research scholarship in art. He’s creating work (sculpture, photography, film) and writing theory on artifact restoration as a metaphor for political reconciliation. (It’s okay—I don’t understand it either—just keep reading, that’s not what this is about anyway.)

As he travels daily between Greek- and Turkish-controlled Cyprus, traversing across a line in the sand, he Whatsapps me journal articles and critical art theory. In lieu of telling me what he’s actually doing or writing or making art about, I’m left to distill his physical and mental locations from the content of his daily cannon. And it seems, even on an island in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, he can’t help but think about the political division we mainlanders are reading about and living in and desperately trying to mend. Recently, he sent along an article by the postmodern non-rationalist political theorist Chantal Mouffe discussing this exactly and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since.

Open up a newspaper—just kidding, no one’s done that in years, open up _The New York Times_ app—and you’re greeted with one of two kinds of stories. I bet you ten-to-one the headlines will either read “Look at what _they_ did! Isn’t that terrible? Why did they do that?”, or “Look at what _we_ did! Aren’t we great! Finally, we’re winning again.” Stories on political and ideological difference have become trope-ish and banal in their repetition such that being divided _feels_like the true state of our country. Following this directly, trouncing, slandering, and personally and politically defiling our opponents _feels_ like the only way we can return to democracy and decorum after coming this far down the road. After all, one side has to win, right?

If we can though, let’s digress from this dichotomous assumption. What if there was another path to democracy, or another form of democracy altogether separate from the construct of a winner and a loser? Compromise and understanding feel like distant and entirely unachievable options at this point—but maybe we’re just not thinking about them in quite the right way.

The foundation of Mouffe’s argument requires defining two very similar but unique forms of democratic thought: antagonistic democracy as opposed to agonistic democracy. Mouffe refers to the type of democracy comprised of an enemy and adversary as “antagonistic democracy”—this is the democracy you read about every day. In her own words, antagonistic democracy attempts to “constitute a ‘we’, and distinguish it from a ‘they’. Consequently, the crucial question of democratic politics is not to reach a consensus without exclusion which would amount to creating a ‘we’ without a corollary ‘they’ but to manage to establish the we/they discrimination...”

The theory of antagonistic democracy recognizes that “we live in a world where a multiplicity of perspectives and values coexist and, for reasons it believes to be empirical, accepts that it is impossible for each of us to adopt them all. But it imagines that these perspectives and values, brought together, constitute a harmonious and non-conflictual ensemble.” In reality though, this is a fallacy Mouffe says—the ensemble can’t exist. There is no room for harmony after you’ve called your political rival an idiot and a criminal.

Antagonistic democracy necessitates exclusion by way of inclusion. By defining yourself as ‘liberal’ and including certain people in your group, you must necessarily exclude others (conservatives, but also others who fall somewhere else on the spectrum). Yet at the same time, a democracy like this is expected to result in outcomes and rules that all citizens must live peacefully under. Mouffe sees this as absurd: how can we expect compromise and understanding when the foundation of the political bodies is based on excluding people and ideas they fundamentally disagree with?

Her answer to antagonistic democracy and its shortcomings is agonistic democracy. Where antagonistic democracy necessitates a construct of friend/enemy, agonistic democracy exists in the space of the _relationship_ between adversaries. Agonistic democracy is the “distinction between the categories of enemy and adversary...meaning that within the ‘we’ that constitutes the political community, the opponent is not considered an enemy to be destroyed but an adversary whose existence is legitimate. His ideas will be fought with vigour but his right to defend them will never be questioned.” Whereas antagonistic democracy leaves no room for real compromise, agonistic democracy, in its definition of struggle and the real possibility for compromise by avoiding exclusionary/ inclusionary logic, represents a truer form of democracy.

Samuel Chambers, another political theorist, summarizes Mouffe’s argument on the subtle but crucial difference between antagonistic and agonistic democracies well. He writes that “Agonism implies a deep respect and concern for the other; indeed, the Greek _agon_ refers most directly to an athletic contest oriented not merely toward victory or defeat, but emphasizing the importance of the struggle itself—a struggle that cannot exist without the opponent. Victory through forfeit or default, or over an unworthy opponent, comes up short compared to a defeat at the hands of a worthy opponent—a defeat that still brings honor. An agonistic discourse will therefore be one marked not merely by conflict but just as importantly, by mutual admiration...”

The goal of our democracy then should not be to bring two opposing sides together to create consensus through a no-matter-what-I-am-right philosophy, because that’s not how compromise works. We shouldn’t actually be striving for harmony, whether through defeat or compromise.

In actuality, the job of a democracy is to “provide the arena” for conflict and set the ground rules for that conflict, so when enemy and adversary leave the ring, even though one may be victorious, the other is still valid and both sides are able to accept the social, judicial, and political outcomes. Struggle is key to any democracy. When the struggle is over though, we must still be able to recognize our adversaries as valid and respectable. It is in this small space that the compromise and harmony we seek—and true democracy—exists. This arena, these ground rules, are precisely what we have lost in America in the last few years. And I would argue that their loss is what makes all of this feel so dreadful and hopeless so often, for it’s a terrifying thought to think that we’ve lost a fundamental part of our democracy.

I must admit that while Mouffe’s argument is a nice ideal, I have a hard time seeing it play out anytime soon. When the political becomes personal and we begin fighting ideological and social battles through personal attacks, we have failed to be democratic. The question is: at what point down the road of libel and slander can we no longer return to the crossroads of democracy? How many times do you have to scream “Lock Her Up!” or “Impeach the Orange!” before it’s impossible to step back into the arena of decency?

I’ve been thinking about Mouffe and her argument for weeks now hoping that focusing on what she believes to be the truth of democracy I could gain some insight as to how we can actually achieve this in our current political climate. Unfortunately, just having the language and constructs of what an ideal democracy should look like does not an ideal democracy make.

I knew my brother would have plenty of thoughts on the matter, and wanted to know if he had any answers for me. After all, he’s where all of this started. I wanted to know what he, living on an island that is literally divided in two, made of agonistic democracy. I wanted to know if the Cypriots had found a way to make it work. As I left work around 6:00 PM San Francisco time, I called him. The phone rang for a few moments before I realized my mistake. It was 4:00 AM in Cyprus, and he was asleep.

As I walked home in the drizzle and fog, up the hill to my apartment, and my cat, and a warm shower my thoughts on the matter relented a bit. And now, as I write this, I can just only say that this is where hope comes in. This is where hope that we can learn to fight not to destroy and exclude those that are different, but rather that we can fight and at the end of it all, look across the aisle and see ourselves.

_Written by_ **Charlie Wiebe**

_Illustrations by_ **Daryn Ray**

My brother, Will, lives in Cyprus, and the one thing I think we can all take away from his experience there is the simple truth that none of us know where Cyprus is. I think of it akin to finding out that someone you’ve just met on the street grew up next door, or had the same piano teacher as you, or dated

the same guy you did in high school—bonded but distant; shared but unknown. The reason I know that none of us (or you, rather) could find Cyprus on a map is because the exact same expression creeps across the face of everyone I’ve told this to so far—about thirty people in the last four months.

It’s fascinating really, as if they all got together and decided that this was the only appropriate reaction to the statement: “My brother, Will, lives in Cyprus”. The unmistakable countenance appears as they try to place where the fuck Cyprus is on their mental map (and no, not the one in Orange County, that’s Cypress, like the tree). It’s the look you get when you stumble out of an afternoon matinee and realize it’s only 4:00 PM and still quite sunny outside. It’s the squint, as you try and reconcile the preternaturally bright day with your warped perception of time. It’s the head cocked to the side, as if looking at the sun from a slant will make it all make more sense.

I realized some time ago that I should not wait for this look to fade into any sort of correct understanding of where (or what for that matter) Cyprus is.

My answer, which I have repeated word for word each time I’ve seen this expression, is: “Yeah, it’s that island kinda between Turkey and Egypt in the Mediterranean Sea. It’s a sovereign state but half of it is run by the Greeks and the other half by the Turks cuz of some political thing in the ’60s. It’s wild but yeah, that’s where he lives.” The one person I’ve read this cue card to who actually knew the history of the island corrected me that, actually, Cyprus was bifurcated in 1974, not “in the ’60s” but I didn’t change my answer, and it hasn’t really mattered.

I bring Will up because with the ten-hour time difference between San Francisco and his temporary island home our primary form of communication is him sending me articles related to his research and me sending him memes related to nothing. For the past four and next five months he was and will continue to be marooned, in order to complete his Fulbright research scholarship in art. He’s creating work (sculpture, photography, film) and writing theory on artifact restoration as a metaphor for political reconciliation. (It’s okay—I don’t understand it either—just keep reading, that’s not what this is about anyway.)

As he travels daily between Greek- and Turkish-controlled Cyprus, traversing across a line in the sand, he Whatsapps me journal articles and critical art theory. In lieu of telling me what he’s actually doing or writing or making art about, I’m left to distill his physical and mental locations from the content of his daily cannon. And it seems, even on an island in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, he can’t help but think about the political division we mainlanders are reading about and living in and desperately trying to mend. Recently, he sent along an article by the postmodern non-rationalist political theorist Chantal Mouffe discussing this exactly and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since.

Open up a newspaper—just kidding, no one’s done that in years, open up _The New York Times_ app—and you’re greeted with one of two kinds of stories. I bet you ten-to-one the headlines will either read “Look at what _they_ did! Isn’t that terrible? Why did they do that?”, or “Look at what _we_ did! Aren’t we great! Finally, we’re winning again.” Stories on political and ideological difference have become trope-ish and banal in their repetition such that being divided _feels_like the true state of our country. Following this directly, trouncing, slandering, and personally and politically defiling our opponents _feels_ like the only way we can return to democracy and decorum after coming this far down the road. After all, one side has to win, right?

If we can though, let’s digress from this dichotomous assumption. What if there was another path to democracy, or another form of democracy altogether separate from the construct of a winner and a loser? Compromise and understanding feel like distant and entirely unachievable options at this point—but maybe we’re just not thinking about them in quite the right way.

The foundation of Mouffe’s argument requires defining two very similar but unique forms of democratic thought: antagonistic democracy as opposed to agonistic democracy. Mouffe refers to the type of democracy comprised of an enemy and adversary as “antagonistic democracy”—this is the democracy you read about every day. In her own words, antagonistic democracy attempts to “constitute a ‘we’, and distinguish it from a ‘they’. Consequently, the crucial question of democratic politics is not to reach a consensus without exclusion which would amount to creating a ‘we’ without a corollary ‘they’ but to manage to establish the we/they discrimination...”

The theory of antagonistic democracy recognizes that “we live in a world where a multiplicity of perspectives and values coexist and, for reasons it believes to be empirical, accepts that it is impossible for each of us to adopt them all. But it imagines that these perspectives and values, brought together, constitute a harmonious and non-conflictual ensemble.” In reality though, this is a fallacy Mouffe says—the ensemble can’t exist. There is no room for harmony after you’ve called your political rival an idiot and a criminal.

Antagonistic democracy necessitates exclusion by way of inclusion. By defining yourself as ‘liberal’ and including certain people in your group, you must necessarily exclude others (conservatives, but also others who fall somewhere else on the spectrum). Yet at the same time, a democracy like this is expected to result in outcomes and rules that all citizens must live peacefully under. Mouffe sees this as absurd: how can we expect compromise and understanding when the foundation of the political bodies is based on excluding people and ideas they fundamentally disagree with?

Her answer to antagonistic democracy and its shortcomings is agonistic democracy. Where antagonistic democracy necessitates a construct of friend/enemy, agonistic democracy exists in the space of the _relationship_ between adversaries. Agonistic democracy is the “distinction between the categories of enemy and adversary...meaning that within the ‘we’ that constitutes the political community, the opponent is not considered an enemy to be destroyed but an adversary whose existence is legitimate. His ideas will be fought with vigour but his right to defend them will never be questioned.” Whereas antagonistic democracy leaves no room for real compromise, agonistic democracy, in its definition of struggle and the real possibility for compromise by avoiding exclusionary/ inclusionary logic, represents a truer form of democracy.

Samuel Chambers, another political theorist, summarizes Mouffe’s argument on the subtle but crucial difference between antagonistic and agonistic democracies well. He writes that “Agonism implies a deep respect and concern for the other; indeed, the Greek _agon_ refers most directly to an athletic contest oriented not merely toward victory or defeat, but emphasizing the importance of the struggle itself—a struggle that cannot exist without the opponent. Victory through forfeit or default, or over an unworthy opponent, comes up short compared to a defeat at the hands of a worthy opponent—a defeat that still brings honor. An agonistic discourse will therefore be one marked not merely by conflict but just as importantly, by mutual admiration...”

The goal of our democracy then should not be to bring two opposing sides together to create consensus through a no-matter-what-I-am-right philosophy, because that’s not how compromise works. We shouldn’t actually be striving for harmony, whether through defeat or compromise.

In actuality, the job of a democracy is to “provide the arena” for conflict and set the ground rules for that conflict, so when enemy and adversary leave the ring, even though one may be victorious, the other is still valid and both sides are able to accept the social, judicial, and political outcomes. Struggle is key to any democracy. When the struggle is over though, we must still be able to recognize our adversaries as valid and respectable. It is in this small space that the compromise and harmony we seek—and true democracy—exists. This arena, these ground rules, are precisely what we have lost in America in the last few years. And I would argue that their loss is what makes all of this feel so dreadful and hopeless so often, for it’s a terrifying thought to think that we’ve lost a fundamental part of our democracy.

I must admit that while Mouffe’s argument is a nice ideal, I have a hard time seeing it play out anytime soon. When the political becomes personal and we begin fighting ideological and social battles through personal attacks, we have failed to be democratic. The question is: at what point down the road of libel and slander can we no longer return to the crossroads of democracy? How many times do you have to scream “Lock Her Up!” or “Impeach the Orange!” before it’s impossible to step back into the arena of decency?

I’ve been thinking about Mouffe and her argument for weeks now hoping that focusing on what she believes to be the truth of democracy I could gain some insight as to how we can actually achieve this in our current political climate. Unfortunately, just having the language and constructs of what an ideal democracy should look like does not an ideal democracy make.

I knew my brother would have plenty of thoughts on the matter, and wanted to know if he had any answers for me. After all, he’s where all of this started. I wanted to know what he, living on an island that is literally divided in two, made of agonistic democracy. I wanted to know if the Cypriots had found a way to make it work. As I left work around 6:00 PM San Francisco time, I called him. The phone rang for a few moments before I realized my mistake. It was 4:00 AM in Cyprus, and he was asleep.

As I walked home in the drizzle and fog, up the hill to my apartment, and my cat, and a warm shower my thoughts on the matter relented a bit. And now, as I write this, I can just only say that this is where hope comes in. This is where hope that we can learn to fight not to destroy and exclude those that are different, but rather that we can fight and at the end of it all, look across the aisle and see ourselves.

_Written by_ **Charlie Wiebe**

_Illustrations by_ **Daryn Ray**

.JPG)

.jpg)