We hear an awful lot about “balance” these days. How to strike it, achieve it, advocate for it, pursue it within. And what’s to balance? The bass and treble? The checkbook? The foolhardy idea of a work/ life compendium? In 2020, we’re maybe balancing our reactions to the seesaw of political bullshit. We’re balancing upended routines with an attempt at remixed normalcy. We’re balancing our chakras, our levels, who and what to follow, our ratio of “at risk” behavior to that of “totally safe”, our savory popcorn with searing substance, our online and offline, our longing with patience.

Contemporary artist Marcel Dzama, who contributed entirely exclusive artwork to this cover story, is something of balance’s folkloric trickster. You sorta imagine him working in his studio in a Zorro mask, a blow dart gun in his belt, perhaps a crystal ensconced silver bullet around his neck. Dzama, rather than suggest a clear route to sanctity (or peril), presents options. And the balance is in the bushel. Marinate in the meta-macabre, bask in benign brutalism, or emancipate in the timeless chancery of whimsy, mischief, and kink. Double take. Glower or smirk. Whatever your choice, the artist’s tickling at your dispositions and desires—your tentacular sub-stimuli.

See, Dzama—who has been represented globally by David Zwirner for a number of years, and whose output includes drawing, painting, filmmaking, costuming, and installation— possesses and expresses a toothily endless and oft-weapon-wielding imagination. The work glows with recognizability. You know his shit when you see it. And it pretty much all adds up to a sparkling career to date, with a handful of occasional shining star collaborators at his side, who fan across respective artistic sandboxes of their own.

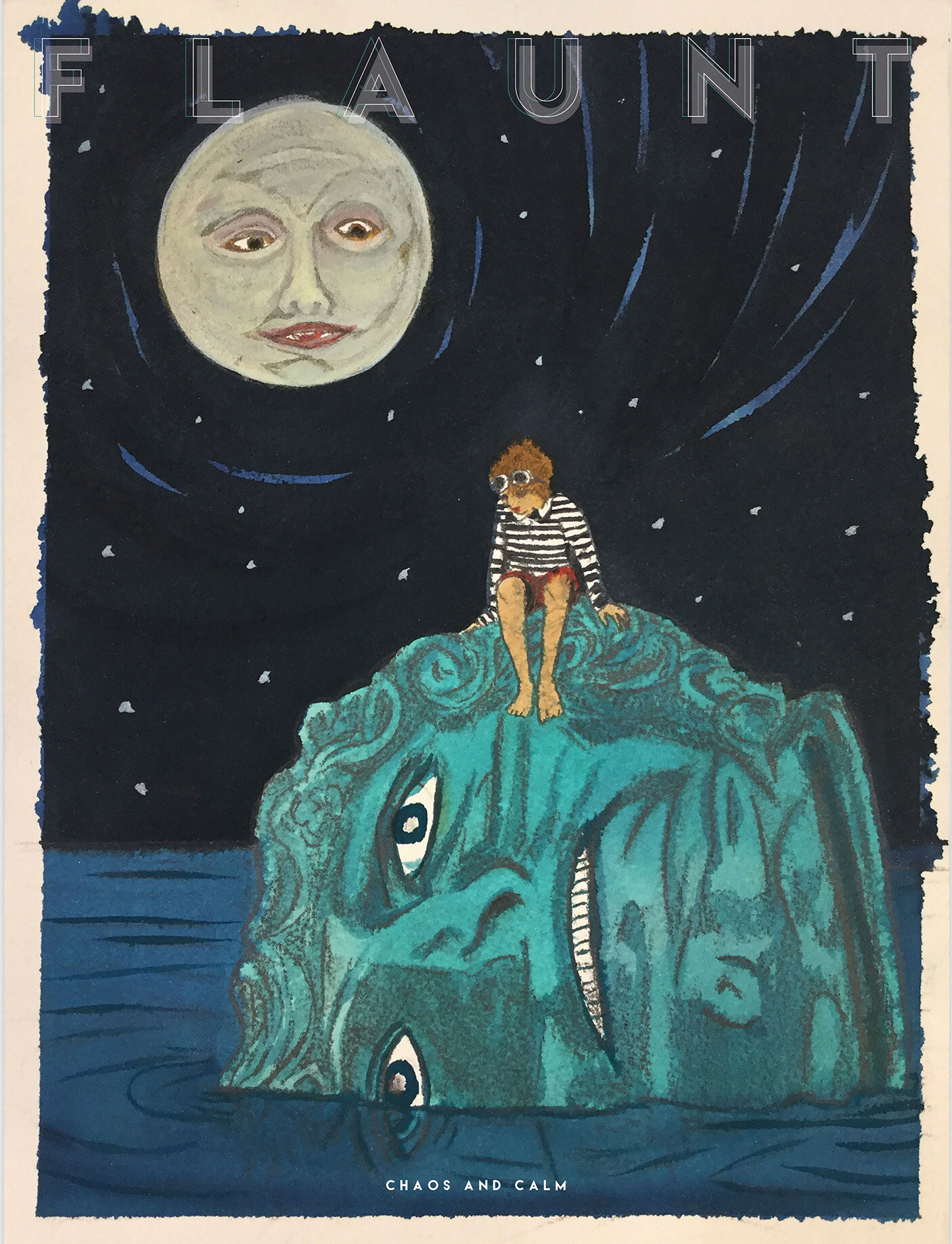

Next, considering we built this magazine around the tug- of-war between Chaos and Calm, the NYC-based Canadian (via Winnipeg) artist seemed an entertaining prospect to craft its Art Cover. A would-be bullseye, frankly, with knee socks! Then, comically, and let’s just say it—Dzama-ically—the custom creation did exactly what the artist has done for the better of two decades: lured and entranced based on preconceptions, and then coquettishly flipped the script.

Dzama laughs over the phone from NYC when I commend his cover creation, my contextualizing it as a “decapitated Statue of Liberty head”, presumably in response to the fall of empire we’re witnessing with greater breakneck speed (get it?) than fathomable. “So, I kind of implied that it was more of a David and Goliath, though it looks more like the Statue of Liberty’s head,” he chuckles. “That is actually my son on the top of the head. I took photos of him posing on a rock on the beach, back when there wasn’t coronavirus, because I was doing a series of travel drawings based on the time before coronavirus, just sort of drafts and sketches.”

MARCEL DZAMA. THE MUSIC STARTED AND IT’LL BE HERE WHEN WE’RE GONE. (2020) © MARCEL DZAMA. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER.

MARCEL DZAMA. THE MUSIC STARTED AND IT’LL BE HERE WHEN WE’RE GONE. (2020) © MARCEL DZAMA. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER.

I ask him about the act of drawing based on photographs he’s taken. “Before I would draw,” he offers on his process, “I usually kind of collected things, like weird labels or something from old magazines, but the last little while, I’ve been taking photographs and working from them, or if I have more time, I will actually sit and sketch something that is in front of me. I think a lot of it, like my earlier work—I mean, I guess I could have drawn Winnipeg, but I was drawing more surrealist things and stuff that didn’t exist—more like taking from dreams and things like that, and not from any reality.” A Winnipeg Winter Wonderland at the very least? “No, it’s almost too cold in the winter there, so it’s not even pleasant. You can’t even build a snowman, because the snow is too cold and it doesn’t stick.”

Returning to the cover artwork, Dzama remarks, “I was kind of hoping that this one was a sign of victory over Trump, but it can definitely read as how bad things have gotten in the last while, as the Statue of Liberty tumbles down to the sea. I actually prefer your read over mine, because it kind of explains this year more than the opposite. I am just trying to be more hopeful than that.”

We speak about the immense challenges faced by so many at the moment, and of course the disproportionate trickle down. “Hopefully, that’s the one thing when we come out of this,” he remarks, “that people will be more supportive of people in harder situations than themselves. Just knowing that there is less of a safety net than some people imagined there was.” Dzama, considering safety nets, remarks at the outset of our interview at his fortune in having a backyard in NYC during the stay-at-home orders, where he and his authorized to be within arm’s reach spent whatever time they could.

And he kept busy. This spring into summer, he opened two shows—one via Zwirner’s speedily engineered digital exhibition portal—both of which were really nice, and both of which arguably annunciate on the desire mentioned above to counterpose on the chaos... to, well, holiday. To whit:

Pink Moon, which opened in May, derives from a trip last year to Morocco. It features scenes of the anticipatory subconsciousness at wrestle, but poolside, chilled out, calming. Some of the drawings aren’t even that weird!

We discuss

Pink Moon further, and it becomes apparent that in addition to being something of fantasy’s tight rope trickster, Dzama is also something of a wolf man. “During that show, there was an actual pink moon that happened,” he says enthusiastically, and then considers the prophetic moon’s role in the genesis of the show, “but I guess some of the drawings had the moon in them already. Actually, Justin Peck, he is a choreographer in the NYC ballet—and I did a ballet with him, three or four years ago—we were talking about doing another one, and I wrote a short story about these little kids that get turned into moths and fly off to the moon. I thought it would be a good children’s ballet story. I did a lot of drawings of the moon for that concept, and then, I think he was working with Steven Spielberg on something, some big movie [

West Side Story], so it got postponed, but I was still drawing the moon after that.” He continues to describe a planet-themed collaborative album he did moons artwork for with Bryce Dresner of the National and Sufjan Stevens.

MARCEL DZAMA. CANNON- BALL (2020) © MARCEL DZAMA. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER.

MARCEL DZAMA. CANNON- BALL (2020) © MARCEL DZAMA. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER.

Talk about balance. The fucking moon! The moods, the phases, the cycles of the sea. “I’ve always been fascinated by the moon because of the dream-like quality, and I always feel like I am messed up when there is a full moon,” he continues. “It’s hard for me to sleep and I end up staying up until it’s daylight out, usually drawing. I’ve also been fascinated with the wolf man since I was a little kid. I used to do drawings of werewolves when I was in grade school. And with the show, with the spring birth, I thought of it as the beginning, because the pink moon is the beginning of spring, representative of a rebirth type thing. And then, also, Nick Drake had that great album.”

We return to the serenity of his recent works, and I ask him to elaborate. “I’ve been finding that, because things are so chaotic,” he considers, “usually my work used to feel very apocalyptic and almost like a warning sign of what was going to happen, but I almost feel like, now that we are in the apocalypse, I am trying to draw something more hopeful and relaxing. I almost feel like it would be preaching to the choir if I was just doing more apocalyptic things. Still every now and then I have to, like if I see something that is really wrong in the world, I have to at least make a journal drawing so I can go to sleep.”

And how are we sleeping? When Dzama and I speak we are less than 90 days from the November presidential election. There’s over 150,000 Covid-19 attributed deaths in the US. Fewer than half of the 23 million jobs lost in March and April have recovered. New satellites have rocketed skyward that are already measuredly scrambling our brains, and some days later Beirut will explode—no, not “an attack”, as declared by our president, but certainly an act of neglect (and what’s the difference?). And let’s not discount the immeasurable amount of live tele-theatrics that you couldn’t write if you tried. “What’s driving my drawings is a lot of just reading the newspaper or listening to the news,” Dzama shares, audibly cringing at the leadership fail during this critical juncture, “Because everything is so obvious with this administration that it seems like ‘Why is it happening? How did this happen? It feels like some B movie writer took over reality and they’re just writing this terrible plot that shouldn’t even exist. Like when the History Channel starts telling this, it’s just going to feel like fiction. And we are probably not even that deep into it yet, like I am sure so much is going to be revealed, like 10 years from now, of how terribly corrupt this was.”

Featured herein, for example, an artwork by Dzama presumably culled from the media’s 24-hour image saturation—and given wings. A woman of color sits on the ground, cradling a dove over her bent and folded up knees, while riot gear policemen loom over her. The dove, of course, emits more poetry than the batons of the police as they catch Dzama’s ubiquitous moonlight, and perhaps here calm has won over chaos. “It feels like we’ve hit—if we were a drug addict or alcoholic—we’ve hit the gutter now,” he remarks, reflecting on the more politicized artwork he’s created this year, some of which features on his Instagram feed, “and hopefully we are gonna rise out of it. Like you hit that rock bottom and either we perish, or we reform.”

MARCEL DZAMA. A NEW AGE BAPTIZED IN PEPPER SPRAY (2020). © MARCEL DZAMA. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER.

MARCEL DZAMA. A NEW AGE BAPTIZED IN PEPPER SPRAY (2020). © MARCEL DZAMA. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER.

I ask Dzama if he sees collaborations or re-connecting with collaborators an important next step for coping with the above as the pandemic flattens out in some cities. “Historically,” he remarks, “I am good with isolation for about 5 months, or something like that, and then I get tired of it and need to socialize. Usually, my reasoning for getting with friends is to make a film, or play music for a film soundtrack, or something like that. I’ve been working with Arcade Fire, and a little bit with LCD Soundsystem. I don’t know how I became friends with all of them, just over the years. Or other artists like Jockum Nordstrom. He is an artist at the gallery as well, and we’ve been playing blues music together. He introduced me to a lot of older music. We used to send mix tapes to each other—cassettes. He would make a cover and everything, like a collage, and everything was handwritten—they definitely could be released as a compilation of some sort. Raymond Petition and I have been writing back and forth to each other and sending little drawings, too, so that has been a nice little thing.”

Dzama’s contribution has been a nice little thing, something I expected to toe the line, as illumined above, but perhaps more steeped in perversion or havoc. There’s enough of that out there at the moment, though, a little more twisted. It seems the artist would agree. Speaking of what’s out there, I ask about the art scene, the digital auctions and fairs, the mobilization within the art world to continue showing, selling, speculating. He admits he’s not paid it much mind, then quips (and cites Paul McCarthy), “It’s like, you know your parents are having sex, but you don’t want to see it.”

To conclude, I ask Dzama about a curatorial statement he made in 2017 to drape a show he organized for David Zwirner at Independent Brussels:

The Mask Makers. The exhibition included Wolfgang Tillmans, Marilyn Minter, Sherrie Levine, and many others hand-picked by the artist, and explored the mythology and symbolism of veils, facial obfuscations, and of course, masks. Looking back, the curation is all the more punchy in a year when the act of mask wearing has become safety, elective, symbolic, and like everything in this country—politicized. The statement?

Be what you want to be, the mask is freedom, anonymity, a new identity or gender, and bridging us to the afterlife.

He reflects on this and remarks, “I guess I was ahead of my time. Interesting how mask wearing has become a political statement. It’s sad that the far right can manipulate people to not believe in science.” And then, after a pause, “Maybe now the mask will save us from an early afterlife.”

MARCEL DZAMA. THE TRAIL OF TEAR GAS (2020). © MARCEL DZAMA. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER.

MARCEL DZAMA. THE TRAIL OF TEAR GAS (2020). © MARCEL DZAMA. COURTESY THE ARTIST AND DAVID ZWIRNER.