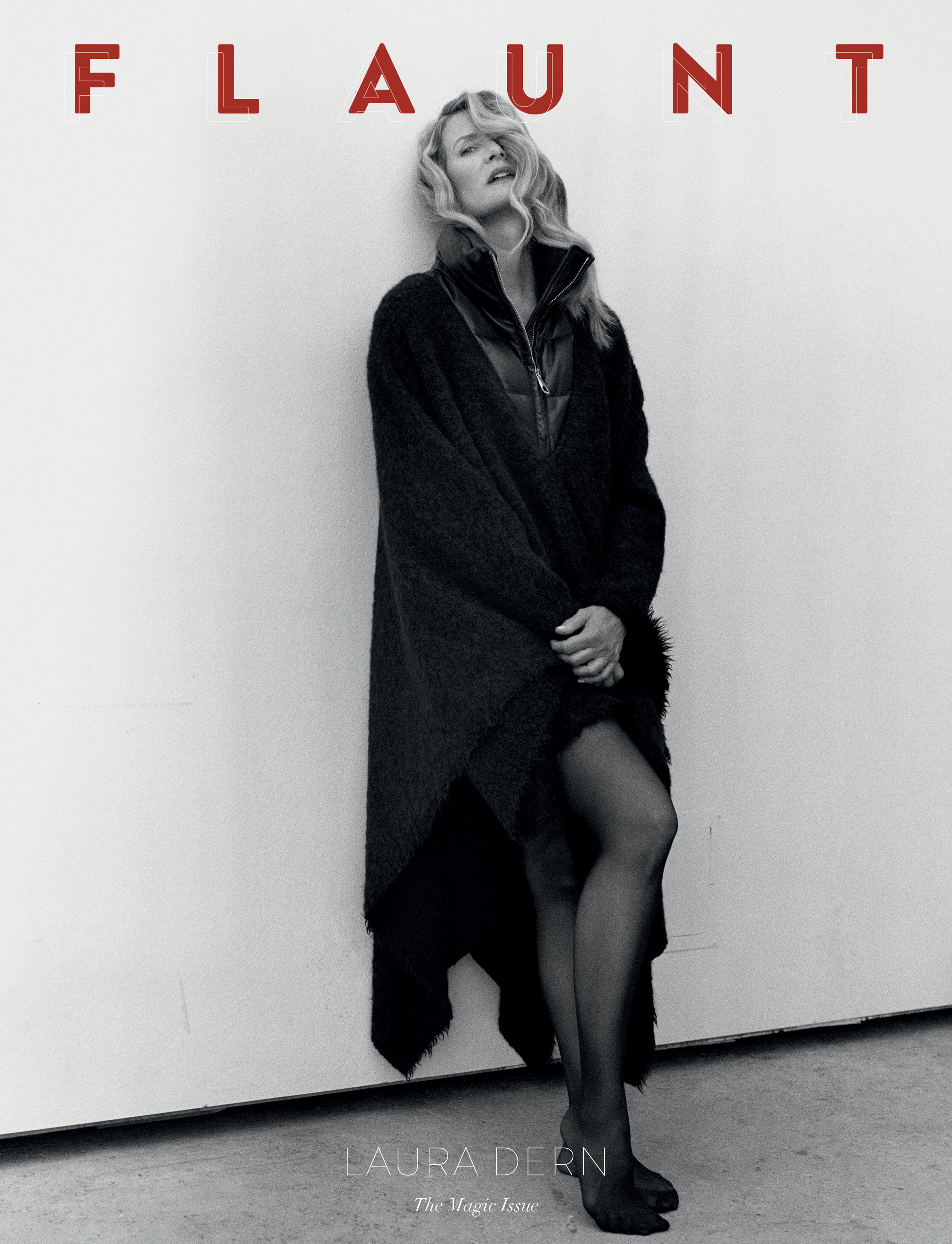

When discussing magic with an Oscar-winner, a cinematic scion, a performative rebel rouser, one might expect tales of lavish sets, near to impossible but realized scenes, the sparkle and twinkle of the carpet, the fanfare. fetes. and first class everything. But when discussing magic with Laura Dern, something altogether different transpires.

Dern has played all kinds of people. Addicts, matriarchs, renegades, heroines, spiritualists, paleobotanists, disciples, servants, and presumably the most ethically uneasy-making—attorneys. Across a 40-year plus career, she’s shared screens with, and been directed by, a litany of the uber-famous and exceptionally talented. She’s done state of the art CGI and crude handheld. She’s done a good bit of David Lynch. She’s ground it down and ground against it, and whined, marauded, and sneered. She’s melted down and melted us. She’s one of our true film treasures.

Laura was born to Bruce Dern, who not only mugged for Flaunt a few years back at the delightful Scottish tavern, Tam O’Shanter in L.A.’s Los Feliz, but who has also featured in nearly as many films as he has tours around the sun—give or take 85. Laura’s mother is Diane Ladd, whose sun tours are equal to that of Bruce, but whose film appearances count exceeds the ormer’s by roughly the age of your humble narrator (do some non-binding projections on the back of the napkin, and let’s move on from this sill analogy). Attached and stretching further back and outward from this exceptional contribution to entertainment are playwrights and Pulitxers, the South, and the first non-Morman governor of Utah and Secretary of War for Frank D. Roosevelt. Laura Dern’s kin runs deep.

BOTTEGA VENETA dress and CARTIER earrings.

But kin, as essayist David Brooks wrote in an essay for The Atlantic in early 2020—though something we might all agree we need—has seen its definition debated by anthropologists for decades. Brooks writes, “For tens of thousands of years, people commonly lived in small bands of, say, 25 people, which linked up with perhaps 20 other bands to form a tribe. They hunted together, fought wars together, made clothing for one another, looked after one another’s kids. In every realm of life, they relied on their extended family and wider kin. Except they didn’t define kin the way we do today. We think of kin as those biologically related to us. But throughout most of human history, kinship was something you could create.”

And so Dern has created extensive and extraordinary kin. Through her boundary-less film work, yes, but also through her advocacy and activism, punctuated by Brooks’ citation of this malleable word vis-a-vis other scholars: kinfolk are “mystically dependent”; “members of one another”; share a “mutuality of being”. It’s easy to imagine Dern absolutely loving this word.

We’ve witnessed Dern wield her words. Words sometimes well-chosen, sometimes spilling out, hemorrhaging from the churning pit of her stomach—in the context of kinships substantive, bro- ken, distorted, and domestically germane. Words in her Academy Award-winning performance in 2019’s Marriage Story, as she spells out the gritty, disproportionately bloated reality of marriage role inequity to a spellbound Scarlett Johansson. Or when she comparably spells it out, through a strained and threadbare yet ascendant voice, to a pessimistically wayward Reese Witherspoon, her daughter, in 2014’s Wild, that she lives with no regret at marrying “an abusive, alcoholic asshole”—despite the economic impact and the trauma—because it created for her a daughter she’s able to speak to in moments like this, or any other. Words bubbling into rage as she’s white-knuckled prying the elevator open in TV series Enlightened, mascara streaking down her face and sobs heaving inside her, as she confronts the man responsible for her spirit-crippling de- motion, the outcome of her having had an affair with him, and with him, his professional and patriarchal seniority. Or reach- ing further back, to an era when Dern was perhaps more known to feature in incendiary and provocative cinema—words desperately projected into the face of groups that amass from both sides of a political divide, to insist on what choices she ought to make with her pregnant body in the un-paralleled Citizen Ruth (1996). This is a film I’d hoped to ask her about. Dern remarks on it voluntarily, though, when we consider the unraveling of social and political progress in the U.S. at present, as Texas emerges as the most grave abortion rights battleground in decades.

GUCCI dress, VALENTINO shoes, CARTIER earring, and BVLGARI rings.

Dern and I will talk about words and their dualistic power and meaninglessness in both films and waking life, and we’ll ar- rive at something similar to Brooks’ compelling and intensively researched framing of what’s gone missing in contemporary family life: there’s not really a word for all this—this need in modern life. A response to all this scale. This evolution of ethics, while the world imposes itself more and more menacingly around us. What will compel us forward is something far more profound, far more abstract.

But there is conversation. That we can always hope to have, for that is where the ripples can be observed and felt. And it’s this space, I think, that Dern is perhaps most living for. Yes, there’s Jurassic World: Dominion in 2022. We may see her return in her Emmy and Golden Globe-winning role as Renata Klein for a third season in HBO hit, Big Little Lies. There will be no doubt powerful results of her current film, now in production—Florian Zeller’s The Son. Her role as a fundraising leader will enjoy a ribbon cutting of sorts when the long-awaited, Renzo Piano-designed Academy Museum of Motion Pictures opens this Fall in Los Angeles. Her contributions to the American Lung Association will continue. Her production company, the aptly titled Jaywalker Pictures, which she co-founded with long-time kindred spirit, Jayme Lemons, will send documentary on White House photographer, Pete Souza—The Way I See It—into the viewing ether.

Yes, all this will kick on. Laura Dern is working more than ever. But it’s the chatter, man. It’s the irreverence and nuance of all this creative foraging that will see her keep the pedal down. Stoking the coals of conversation. The micro and macro. The kinship and its quirks. The kinship and its infinitude. Now, witness Laura Dern do it all with verve and grace.

Foremost, let’s discuss how you spent your day. What can you tell me about your current production?

We are in the middle of a film based on a play by Florian Zeller, that he has adapted and is directing. It’s called The Son, which is the second film after The Father [which saw two Academy Awards and four additional nominations], which he made last year. Such a beautiful film. It’s a very emotional movie, so I am very happy I am with a lovely, amazing group of people. Kind people, like Florian, and Christopher Hampton, who also adapted the play with him, and Hugh Jackman, who is just a dream human. It’s been so wonderful, and it’s just such a great group of people. I am very lucky.

And so my day has been working on that mostly, but also doing ADR on a couple other things. Keeping it all interesting.

And with Florian, what have you observed in his approach to direction? Do you see a fluency that you might see in stage direction? What’s unique about his approach?

I think it’s interesting. When you are lucky enough to work with directors, who, as writers, have a real music and rhythm to their language, there is a very particular and protective way that you bring those words to film, and I feel that very much with Greta Gerwig. I feel that very much with Noah Baumbach. Even though they have their own specific kind of rhythm, it is like you know how the line and the rhythm of the language need to work, while also trying to be honest. I think particularly with Florian and Christopher there, obviously Florian directing, but having Christopher there as well every day at work—which is an amazing thing—we are really considering every word we use and what it means. It’s an adaptation of a French play as well, and there is something very beautiful about honoring the word and that the word has weight—maybe a different kind of weight in different languages. And sort of watching how they work with it is so beautiful. But all of it chips away and Florian only cares about it feeling honest. So he is also not protective at all, which is an amazing talent, and I think even The Father, which I thought was such a gorgeous film, he leaned into—as I am sure he did with his play—the simplicity, with all the noise stripped away, and you are left with, in the case of stories, of both plays, of both films, an issue of mental health. What is really happening here in these relationships? How is it impacting these relationships? Just a total blessing to be with them.

CHLOÉdress.

Would you suggest that the mental health journey is about stripping away layers and noise?

Yes. And I think stripping away shame, so that people are having a conversation about what really is happening, because there is so much shame, as we looked at in The Father, which was dementia. People were in such denial and not looking at what was clearly in front of them, and the shame that’s encased with anxiety and depression. We are a culture of trying to take a pill and get rid of a problem, but there’s not a lot of gentleness with ourselves, or understanding with loved ones in that way. You know, the support in mental health. There is such a commitment to that in his work, especially at this time, in this pandemic, all the political unrest in the U.S., all that is happening, and I couldn’t be more grateful for working on a subject matter that I think we are all looking at, which is how it feels. How grounded or free of anxiety in such troubled times. It’s really been amazing.

And coming back to this idea of language, or words—words can have so much gravitas and implications and influence, and at the same time, there is this sort of adage: ‘It’s not what you say, but how you say it.’How would you say you yourself have related to language as a powerful tool, not only in performances, but in your personal life over time? Are you finding that you are more an advocate for restraint, or is it more about meditating on word choice?

Well, I hope I learn how to. I mean, I consider my words—I consider them deeply as an actor, I worship them, I am so interested in language. I was raised by people who words were critical to for their vocation, I was married to a songwriter, I mean, words matter so much in my family life. And yet, when human beings are vulnerable, insecure, or triggered, the discipline and the art of word choice is something that most of us, I think, will spend a lifetime learning about. I am definitely committed to that lifetime of learning, but I don’t know how often I get it right, and I think especially as a parent, you are so afraid and so longing to say the most supportive or helpful thing. We come from our own history and not always know how to do that. So, yeah, just constant education.

PRADA coat, boots, and gloves and BVLGARI necklace.

It makes me think about the format of this conversation being an interview. How do you stand on interviews at this stage in your career? Do you prepare? Is there a wariness? How are you relating to interviews at present?

I really enjoy conversation, and I’ve never been wary until that feeling comes over you when someone is asking questions that feel hurtful, or down a particularly personal path that you are surprised by, things like that. It has been very rare in my career, but there were maybe three that were hurtful, like I was going through a hard time, and that’s right where they go, but most experiences I’ve had have been really beautiful. In fact, like writer / director friends, which are some of my closest friendships, I’ve had a few journalists where we’ve met, and just in that hour, we had such a beautiful time getting to talk as human beings, and it’s become a wonderful friendship. I am such a fan of writers, so I think I see it as an opportunity to have an honest conversation. I don’t know if you’ve felt this way, but I feel like in the last year plus now, the few interviews that we’ve done during the pandemic are completely different. And the journalist is usually creating some autonomy, and I feel like now, it’s much more a conversation of like, ‘How are you doing? And how are you doing? How does that feel? What’s that like for you?’ Because we are all in this space that is completely different. Everything has changed. What’s important to us, or what holds value has changed for us, including the readers, so the conversation has changed, which I think is very healthy.

In a recent article, you were speaking to the growth process of characters that you relate to. You said that you are more drawn to incremental change than drastic. I think, artistically, we can appreciate these sort of small steps forward, but in our waking life, we sometimes desire for more dramatic results. Would you agree? Can you speak to that?

Well, beautifully put, and I absolutely agree. I think that’s why I love storytelling that involves incremental growth, because it’s more relatable. And maybe by seeing it, we’ll be kinder to ourselves about those small victories, and not waiting for the superhero ending, where everything is perfect and you get the girl, and you save thousands of people, and everything just goes dandy. I mean, I love some fantasy, and I love love stories, and I love superhero movies, but I like them when they are filled with some complication and some irreverence, and subtle. Growing up on movies as a kid, movies were really my hobby. You know when people ask ‘What did you do as a kid? Did you play sports? What?’ My family, we really just watched movies. I learned a lot from them, but I also dreamt of things that weren’t realistic, you know, and I love filmmakers that find happy endings within complicated people, and that it’s still a happy ending, but it’s an honest happy ending. It’s still delicious, and bittersweet, and hopeful, still filled with longing, or some insecurity, but it still is truly a happy ending. I think that is, you know, a beautiful place to be with ourselves. But absolutely, I agree that it’s not our orientation, and that’s probably why movies are often not like that—because we are waiting for the... you know, we want to win the lottery. And we go every day and buy a lottery ticket, and we don’t pray that we are going to find five grand. We pray that we are going to make 100 million dollars. And we want to meet the perfect partner—not an imperfect person who is really loving, and kind, and super funny, and willing to work on their own struggles and journey, while you’re on yours. Somehow, that doesn’t sound as sexy to people. It does to me. And maybe it’s because the perfect plan—I am now old enough to know—and looking for perfection can lead you down a troubled path, as opposed to being around authentic friends, family, and lovers.

GIVENCHY jacket and skirt, GABRIELA HEARST pants, and CARTIER earrings, necklace, and rings.

And as a mother, and also a witness to youth culture and an up-and-coming generation, do you feel, or are you observing a similar sort of preoccupation with perfection? The big home run, lottery ticket hopes? Or do you find that, perhaps there’s a little bit more appreciation for measured growth?

Listen. I absolutely do. And I think it’s certainly this generation of teenagers and young adults right now who have witnessed the last several years politically, you know, for American kids, and globally, in terms of both the pandemic and our environment. Now they’re into, like, saving us from disaster, not looking for the unachievable perfection. They’re like, ‘Okay, how are we going to still have a home? How do we avoid school shootings? How do we get people to talk to each other? How do we finally create a world where racism isn’t leading every workplace environment choice, every case of police brutality.’ I mean, it’s just, they’re cleaning up a mess. They’re not fantasizing about a perfect future. And that’s heartbreaking. But it’s also realistic. They’re like, ‘You guys, you poisoned us. You poisoned the water supply, poisoned the ocean, poisoned the soil. You have created this disaster when it comes to our ozone layer. But now we’ve got to figure out: how do we fix this enough that we’re safe?’ They’re not running around going, Well, in two years, there’s never going to be another fire, another tornado, no sea level rise. I mean, they’re adopting sort of a survival mentality, not a dreamer mentality perhaps. That’s what I see.

In a culture so historically defined by dreaming, where do you see the potential adverse effects of that sort of hard-line realism, as opposed to idealism?

Well, I think if the whole world, right, as dreamers and the new generation of survivalists and realists came together and said, ‘You know what? Given the world order, consumerism can’t be part of the dream, guys. It doesn’t work. You don’t get your vacations, and your fossil fuels, and your dumping in the bay, and your using plastic because it’s easier, and, use it ’til you don’t want it anymore, and then get all new stuff.’ Right? That’s just not the world we live in, so we gotta build another dream. So, I think from their approach, hopefully the dreamers will still get to dream, but they’ll dream things like, ‘Oh my god, soil can save us. We have what we need—in terms of saving ourselves—and it’s right under our feet.’ And how exciting is that? That’s a new dream. Let’s get out there. Let’s plant, let’s create regenerative farms, let’s take on industrial farming and look at how to do this differently. What an exciting time to dream of a new way of providing the globe with food and resources, as opposed to, I want what’s mine, and I’m going to take it even if it means leaving everybody else out.

GIVENCHY jacket and skirt, GABRIELA HEARST pants, and CARTIER earrings, necklace, and rings.

So in a sense, the dreaming hasn’t ceased, it’s evolved, and it’s less about material sort of gain or amassing, but still the poetry and love and magic, so to speak, are alive and kicking in the young psyche.

Yeah. You know, my daughter loves her school she goes to. She goes to a wonderful school, fairly newly in the last couple of years. It’s not huge, and it doesn’t have the giant field, and it doesn’t have a million sports teams. Its emphasis isn’t about being a theatre school to the biggest Ivy League schools, its emphasis is on community, and kindness, and true diversity. Creating a community that looks like real life in a school environment, and treating teachers well and treating students well. She just loves it so much for those reasons, and I find that so moving, that she wanted to make a change, but she didn’t need all the bells and whistles. She just needed to feel safe, and safe for her was something that reflected the world as it is—not this protected, created world. You know what I’m saying?

To the tune of what you’ve been speaking about—this kind of broad stroke calamity on planet Earth—I came across a remark you’d made before, where you talk about finding kind of humor in broken places. It feels there aren’t little broken places anymore—the whole thing is broken. I was curious if you’re seeing that reflected in storytelling, and is there still sort of a desire to find granular stories? Or are you thinking there’s more energy dedicated to addressing these kinds of larger crises?

Yeah. I mean, I pray there’s room for both. I pray there’s room to take on massive stories in a granular way. Which I think Florian is doing, right? This massive theme of mental health in a raw, vulnerable, tender way. It’s just mind blowing to me. As is the exciting and amazing group of filmmakers—in both my mentors and people that I kind of grew up learning from—who are still doing extraordinary things and asking extraordinary questions, like say, from David Lynch to Steven Spielberg, all the way to this new generation of filmmakers. And there are filmmakers I don’t know that are definitely looking at it radically differently, like the Safdie brothers, who I think are really looking at fractured insecurity, and consumerism, and relationships. And they’re doing it as, before, like you mentioned, they’re looking for the humor, the irreverence in those places, which is why I feel so lucky to have worked with the group of people that I have gotten to work with thus far. Whether it be David or Alexander Payne, or Noah Baumbach, Greta Gerwig, Andrea Arnold, all the way to Mike White. They are all also looking for that balance. I just think it gives us insight into ourselves—it cracks the story open so that you can relate. And, you know, hopefully, even in the world of big commercial franchise films, you can find like-minded people who want to find the opportunity to tell something deeper about people, or about what’s going on on the planet, or relationships. And young filmmakers, thank God, and female storytellers more and more. That’s exciting.

CHLOÉ poncho.

You’re now in a position where you can offer mentorship on set. You’ve been in receipt of a lot of mentorship on set. What do you feel is something you have personally sought to pass on that you were in receipt of, as a mentor?

Well, with fellow actors, it’s a group effort. So whether you are the person who’s worked the most, or the newest actor, it doesn’t matter. You are there together to remind each other to be honest. To strip away any idea of how it’s supposed to be, or being performative, or looking for what the result should be. It’s a journey towards truth. There’s no right or wrong. And I would say that for all of us. I mean, the organism that is a movie crew is a group of people that come from their own family histories, and if you’re going to make a great film, we have to trust ourselves deeply. And if you’ve got a deeply insecure narcissist, or you’ve got someone who doesn’t feel their opinion matters, your movie goes down. You know what I mean? That’s been the greatest lesson to watch. It’s everyone equally respecting each other. And the great leaders, in the filmmaking, are the ones who make it a party for everybody. Of everyone I worked with, Robert Altman would be someone I put at the top of that list. Bob made it a party for everybody. Everybody came to Bailey’s every night, and it was always great food and a good time. He would see his set decorator or his prop master kind of stressing in their mind... a prop not seeming right, off the set kind of looking at it, but not saying a word, and he would go, ‘Wait, come here. What don’t you like? I see you don’t like something?’ And they’re like, ‘Well, if it were me, I don’t think that character would be reading a book. Like, he seems like a guy who hasn’t read a book in 20 years.’ And Bob was like, ‘Oh, my God, I didn’t catch that. Jesus Christ, I was gonna let that kid read a book... You’re so right.’ I mean, it takes this massive team to catch every moment for each other, and there’s no one more important. I mean that lesson was huge.

There’s a construct whereby everyone is capable of poisoning the well, but everyone’s also capable of creating a safe space, or a celebratory or a jubilant space?

Exactly, exactly. And I mean how to be outspoken, and ambitious and trusting of oneself with absolute humility is a lifelong journey. I can’t wait to get there. I’m just learning.

As you’re describing that kind of consummate positivity on set, you know, it brings to mind the theme of this issue, which is magic. And magic is a word that is, of course, bandied about showbiz. I wanted to ask how you might relate to the concept of magic? Is it that of spontaneity, or when everything kind of finds alignment?

Something unseen, something much larger than we know. That’s all magic to me. And magic is also effortlessness. When something feels so effortless. You know, a child at play, or Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in Swingtime—all things that feel so effortless are so magical.

CHLOÉdress.

And sometimes the irony that perhaps a lot of effort preceded the payoff?

Yes, exactly. And that you don’t see it. That moment is so beautiful. That’s magical.

Speaking of effort, I wanted to briefly touch on a remark you made in an interview previously about scenes that might not be shot today, or couldn’t be shot today, given their social volatility... let’s call it. Is that something you feel holds true for a lot of your work? Do you feel there were experimentations with power structures, or sexuality, or even violence that today might not see light because of a more complex social situation? Do you agree? Do you feel like those are only a handful in number? How do you relate to scenes you say might not be shot in, say, 2021?

Oh man. I feel like most things I’ve done, maybe. I think most things I’ve done. I think, rightly, everything is being reconsidered in terms of who deserves to have voice in storytelling. So I don’t know if a specific movie I’ve done with a male writer / director, with a lens toward a female, they might go, ‘Well, how does he know?’ I don’t know that exploring a man’s violence towards a woman... I think it’s considered very differently. It exists, and these are conversations—that’s part of art—but I don’t know if they get made, or in the same way, or with the same freedoms. Tragically, the first movie that actually comes to mind is actually Citizen Ruth. And Citizen Ruth needs to be made and seen as, like, required viewing right now in our country. It depicts so brilliantly the divide, and the lack of consideration for a pregnant woman and her own right to choose, and what that looks like, and all sides are divided. Everyone is a target, in a way, by Alexander Payne in that film, which I think is what’s brilliant about it. And it’s done with such incredible humor and irreverence. But, you know, does somebody give you the money to make that film right now? I mean I hope, I think everyone does, but I worry.

I cannot believe that we made a movie about the choice issue in the 90s. And that I think it would be hard to make now— that is just tragic. That is so tragic.

CHANEL blouse, THOM BROWNE skirt, CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN boots, and BVLGARI earrings and necklace.

That begs the question: have we reached a point in culture where even parody doesn’t have legs to stand on because of inequity or a historic poisoning of the well?

As journalists, artists, and filmmakers, we just have to keep exposing truth. That is our job. And however we do it, with humor, with fine art, with an interview, with a documentary, with music—more than ever before, we’ve got to get in the face of anything that still has blinders on. There’s a million ways to do it. We don’t have time to just not think about anything anymore. It’s unbelievable. Unbelievable times, right?

It’s a trip. This miraculous coalescence of nature and mankind’s deepest and darkest.

I remember the night that the President of the United States, and the First Lady and their daughters, came out of the White House to see a rainbow spectacle of light on the White House. Same-sex marriage was finally, after so many horrific years of injustice, was finally seen as truth and law and we were all celebrated. And like, how are we here? How did we reverse history? In a million ways. You know what I mean? That’s crazy to think about. Even for us, we’re like, ‘Well, it’s a little bit of progress.’ I mean, that was massive. It was massive. We didn’t know how massive it was. We were just pissed off we were having to finally celebrate then.

There was this pursuit for something that was never had, and then it was had, and then we came to see how easily it could be stripped away and stomped on. What can you tell me about the documentary you recently co-produced, The Way I See It, and how it relates to this pursuit of sharing of voice?

I mean, I definitely have to give credit to my producing partner, Jayme Lemons, who saw Pete Souza’s book tour, and we both loved his photographs, and the archivist he has been for this country through the Reagan years, as well as the Obama years. The moments he captured are so profound, and we really felt there was something here. And once we sat with Pete, and talked to him about it, he gave us a sense of commitment to the movie we wanted to make, the larger movie, which was: what does nobility and empathy and leadership look like, and it’s not a divide between right or left. It’s just about considering human beings and being their champion. That’s what was most exciting—that he was ready to join the team on that.

CHLOÉ dress.

Maybe we’re entering a space where the adored, or heard, or seen, are persons that aren’t courting the divide, but sort of ascending it. You remarked on how Florian’s set how kindness has been a key agent in the collaboration and creativity. I wanted to close on how you relate to the idea of kindness, and how that’s evolved over time, and why is it important to be kind?

Well, that’s magical. It shouldn’t have to be, but kindness is magic, because it makes magical things happen. And, you know, my mom, and my grandmother, they were always such generous people to everyone, and really thoughtful to offer a meal or something cool to drink to anyone, whoever, you know, a plumber who came to the house.... I think being raised and seeing that, and then when I was moved to a workplace environment, and being on set, and I would see people in leadership positions holding that kind of kindness—that really meant a lot to me. It’s just more fun. And by the way, it’s hard to be fearless with mean people. I just never understood, working as an actor working with mean people, and you’re in a place where you’re trying to do brave work, or boundary-less work... you know? It’s nice to know someone’s got your back. So that’s why when you find people who feel like family, and you’re lucky you get to work with them over and over again.

We always want to see kind and fun people again right? It’s in our nature.

Don’t we? Ugh, yeah! In a way, you kind of see all of it to know how to have an instinct about what real kindness looks like, or who to trust, and it’s a journey to believe in your own instincts about people, and know the difference of what feels kind to you, and how to be kind, even when you’re afraid.

Photographed by Yana Yatsuk Styled by Mui-Hai Chu Hair by Kylee Heath at A-Frame Agency Makeup by Pati Dubroff at Forward Artists Manicure by Kimmie Keyes at The Wall Group Style Assisting by Sky Barbarick & Justice Jackson Videography by Mynxii White Written by Matthew Bedard Location: The Mountain Mermaid, Topanga, CA

When discussing magic with an Oscar-winner, a cinematic scion, a performative rebel rouser, one might expect tales of lavish sets, near to impossible but realized scenes, the sparkle and twinkle of the carpet, the fanfare. fetes. and first class everything. But when discussing magic with Laura Dern, something altogether different transpires.

Dern has played all kinds of people. Addicts, matriarchs, renegades, heroines, spiritualists, paleobotanists, disciples, servants, and presumably the most ethically uneasy-making—attorneys. Across a 40-year plus career, she’s shared screens with, and been directed by, a litany of the uber-famous and exceptionally talented. She’s done state of the art CGI and crude handheld. She’s done a good bit of David Lynch. She’s ground it down and ground against it, and whined, marauded, and sneered. She’s melted down and melted us. She’s one of our true film treasures.

Laura was born to Bruce Dern, who not only mugged for Flaunt a few years back at the delightful Scottish tavern, Tam O’Shanter in L.A.’s Los Feliz, but who has also featured in nearly as many films as he has tours around the sun—give or take 85. Laura’s mother is Diane Ladd, whose sun tours are equal to that of Bruce, but whose film appearances count exceeds the ormer’s by roughly the age of your humble narrator (do some non-binding projections on the back of the napkin, and let’s move on from this sill analogy). Attached and stretching further back and outward from this exceptional contribution to entertainment are playwrights and Pulitxers, the South, and the first non-Morman governor of Utah and Secretary of War for Frank D. Roosevelt. Laura Dern’s kin runs deep.

BOTTEGA VENETA dress and CARTIER earrings.

But kin, as essayist David Brooks wrote in an essay for The Atlantic in early 2020—though something we might all agree we need—has seen its definition debated by anthropologists for decades. Brooks writes, “For tens of thousands of years, people commonly lived in small bands of, say, 25 people, which linked up with perhaps 20 other bands to form a tribe. They hunted together, fought wars together, made clothing for one another, looked after one another’s kids. In every realm of life, they relied on their extended family and wider kin. Except they didn’t define kin the way we do today. We think of kin as those biologically related to us. But throughout most of human history, kinship was something you could create.”

And so Dern has created extensive and extraordinary kin. Through her boundary-less film work, yes, but also through her advocacy and activism, punctuated by Brooks’ citation of this malleable word vis-a-vis other scholars: kinfolk are “mystically dependent”; “members of one another”; share a “mutuality of being”. It’s easy to imagine Dern absolutely loving this word.

We’ve witnessed Dern wield her words. Words sometimes well-chosen, sometimes spilling out, hemorrhaging from the churning pit of her stomach—in the context of kinships substantive, bro- ken, distorted, and domestically germane. Words in her Academy Award-winning performance in 2019’s Marriage Story, as she spells out the gritty, disproportionately bloated reality of marriage role inequity to a spellbound Scarlett Johansson. Or when she comparably spells it out, through a strained and threadbare yet ascendant voice, to a pessimistically wayward Reese Witherspoon, her daughter, in 2014’s Wild, that she lives with no regret at marrying “an abusive, alcoholic asshole”—despite the economic impact and the trauma—because it created for her a daughter she’s able to speak to in moments like this, or any other. Words bubbling into rage as she’s white-knuckled prying the elevator open in TV series Enlightened, mascara streaking down her face and sobs heaving inside her, as she confronts the man responsible for her spirit-crippling de- motion, the outcome of her having had an affair with him, and with him, his professional and patriarchal seniority. Or reach- ing further back, to an era when Dern was perhaps more known to feature in incendiary and provocative cinema—words desperately projected into the face of groups that amass from both sides of a political divide, to insist on what choices she ought to make with her pregnant body in the un-paralleled Citizen Ruth (1996). This is a film I’d hoped to ask her about. Dern remarks on it voluntarily, though, when we consider the unraveling of social and political progress in the U.S. at present, as Texas emerges as the most grave abortion rights battleground in decades.

GUCCI dress, VALENTINO shoes, CARTIER earring, and BVLGARI rings.

Dern and I will talk about words and their dualistic power and meaninglessness in both films and waking life, and we’ll ar- rive at something similar to Brooks’ compelling and intensively researched framing of what’s gone missing in contemporary family life: there’s not really a word for all this—this need in modern life. A response to all this scale. This evolution of ethics, while the world imposes itself more and more menacingly around us. What will compel us forward is something far more profound, far more abstract.

But there is conversation. That we can always hope to have, for that is where the ripples can be observed and felt. And it’s this space, I think, that Dern is perhaps most living for. Yes, there’s Jurassic World: Dominion in 2022. We may see her return in her Emmy and Golden Globe-winning role as Renata Klein for a third season in HBO hit, Big Little Lies. There will be no doubt powerful results of her current film, now in production—Florian Zeller’s The Son. Her role as a fundraising leader will enjoy a ribbon cutting of sorts when the long-awaited, Renzo Piano-designed Academy Museum of Motion Pictures opens this Fall in Los Angeles. Her contributions to the American Lung Association will continue. Her production company, the aptly titled Jaywalker Pictures, which she co-founded with long-time kindred spirit, Jayme Lemons, will send documentary on White House photographer, Pete Souza—The Way I See It—into the viewing ether.

Yes, all this will kick on. Laura Dern is working more than ever. But it’s the chatter, man. It’s the irreverence and nuance of all this creative foraging that will see her keep the pedal down. Stoking the coals of conversation. The micro and macro. The kinship and its quirks. The kinship and its infinitude. Now, witness Laura Dern do it all with verve and grace.

Foremost, let’s discuss how you spent your day. What can you tell me about your current production?

We are in the middle of a film based on a play by Florian Zeller, that he has adapted and is directing. It’s called The Son, which is the second film after The Father [which saw two Academy Awards and four additional nominations], which he made last year. Such a beautiful film. It’s a very emotional movie, so I am very happy I am with a lovely, amazing group of people. Kind people, like Florian, and Christopher Hampton, who also adapted the play with him, and Hugh Jackman, who is just a dream human. It’s been so wonderful, and it’s just such a great group of people. I am very lucky.

And so my day has been working on that mostly, but also doing ADR on a couple other things. Keeping it all interesting.

And with Florian, what have you observed in his approach to direction? Do you see a fluency that you might see in stage direction? What’s unique about his approach?

I think it’s interesting. When you are lucky enough to work with directors, who, as writers, have a real music and rhythm to their language, there is a very particular and protective way that you bring those words to film, and I feel that very much with Greta Gerwig. I feel that very much with Noah Baumbach. Even though they have their own specific kind of rhythm, it is like you know how the line and the rhythm of the language need to work, while also trying to be honest. I think particularly with Florian and Christopher there, obviously Florian directing, but having Christopher there as well every day at work—which is an amazing thing—we are really considering every word we use and what it means. It’s an adaptation of a French play as well, and there is something very beautiful about honoring the word and that the word has weight—maybe a different kind of weight in different languages. And sort of watching how they work with it is so beautiful. But all of it chips away and Florian only cares about it feeling honest. So he is also not protective at all, which is an amazing talent, and I think even The Father, which I thought was such a gorgeous film, he leaned into—as I am sure he did with his play—the simplicity, with all the noise stripped away, and you are left with, in the case of stories, of both plays, of both films, an issue of mental health. What is really happening here in these relationships? How is it impacting these relationships? Just a total blessing to be with them.

CHLOÉdress.

Would you suggest that the mental health journey is about stripping away layers and noise?

Yes. And I think stripping away shame, so that people are having a conversation about what really is happening, because there is so much shame, as we looked at in The Father, which was dementia. People were in such denial and not looking at what was clearly in front of them, and the shame that’s encased with anxiety and depression. We are a culture of trying to take a pill and get rid of a problem, but there’s not a lot of gentleness with ourselves, or understanding with loved ones in that way. You know, the support in mental health. There is such a commitment to that in his work, especially at this time, in this pandemic, all the political unrest in the U.S., all that is happening, and I couldn’t be more grateful for working on a subject matter that I think we are all looking at, which is how it feels. How grounded or free of anxiety in such troubled times. It’s really been amazing.

And coming back to this idea of language, or words—words can have so much gravitas and implications and influence, and at the same time, there is this sort of adage: ‘It’s not what you say, but how you say it.’How would you say you yourself have related to language as a powerful tool, not only in performances, but in your personal life over time? Are you finding that you are more an advocate for restraint, or is it more about meditating on word choice?

Well, I hope I learn how to. I mean, I consider my words—I consider them deeply as an actor, I worship them, I am so interested in language. I was raised by people who words were critical to for their vocation, I was married to a songwriter, I mean, words matter so much in my family life. And yet, when human beings are vulnerable, insecure, or triggered, the discipline and the art of word choice is something that most of us, I think, will spend a lifetime learning about. I am definitely committed to that lifetime of learning, but I don’t know how often I get it right, and I think especially as a parent, you are so afraid and so longing to say the most supportive or helpful thing. We come from our own history and not always know how to do that. So, yeah, just constant education.

PRADA coat, boots, and gloves and BVLGARI necklace.

It makes me think about the format of this conversation being an interview. How do you stand on interviews at this stage in your career? Do you prepare? Is there a wariness? How are you relating to interviews at present?

I really enjoy conversation, and I’ve never been wary until that feeling comes over you when someone is asking questions that feel hurtful, or down a particularly personal path that you are surprised by, things like that. It has been very rare in my career, but there were maybe three that were hurtful, like I was going through a hard time, and that’s right where they go, but most experiences I’ve had have been really beautiful. In fact, like writer / director friends, which are some of my closest friendships, I’ve had a few journalists where we’ve met, and just in that hour, we had such a beautiful time getting to talk as human beings, and it’s become a wonderful friendship. I am such a fan of writers, so I think I see it as an opportunity to have an honest conversation. I don’t know if you’ve felt this way, but I feel like in the last year plus now, the few interviews that we’ve done during the pandemic are completely different. And the journalist is usually creating some autonomy, and I feel like now, it’s much more a conversation of like, ‘How are you doing? And how are you doing? How does that feel? What’s that like for you?’ Because we are all in this space that is completely different. Everything has changed. What’s important to us, or what holds value has changed for us, including the readers, so the conversation has changed, which I think is very healthy.

In a recent article, you were speaking to the growth process of characters that you relate to. You said that you are more drawn to incremental change than drastic. I think, artistically, we can appreciate these sort of small steps forward, but in our waking life, we sometimes desire for more dramatic results. Would you agree? Can you speak to that?

Well, beautifully put, and I absolutely agree. I think that’s why I love storytelling that involves incremental growth, because it’s more relatable. And maybe by seeing it, we’ll be kinder to ourselves about those small victories, and not waiting for the superhero ending, where everything is perfect and you get the girl, and you save thousands of people, and everything just goes dandy. I mean, I love some fantasy, and I love love stories, and I love superhero movies, but I like them when they are filled with some complication and some irreverence, and subtle. Growing up on movies as a kid, movies were really my hobby. You know when people ask ‘What did you do as a kid? Did you play sports? What?’ My family, we really just watched movies. I learned a lot from them, but I also dreamt of things that weren’t realistic, you know, and I love filmmakers that find happy endings within complicated people, and that it’s still a happy ending, but it’s an honest happy ending. It’s still delicious, and bittersweet, and hopeful, still filled with longing, or some insecurity, but it still is truly a happy ending. I think that is, you know, a beautiful place to be with ourselves. But absolutely, I agree that it’s not our orientation, and that’s probably why movies are often not like that—because we are waiting for the... you know, we want to win the lottery. And we go every day and buy a lottery ticket, and we don’t pray that we are going to find five grand. We pray that we are going to make 100 million dollars. And we want to meet the perfect partner—not an imperfect person who is really loving, and kind, and super funny, and willing to work on their own struggles and journey, while you’re on yours. Somehow, that doesn’t sound as sexy to people. It does to me. And maybe it’s because the perfect plan—I am now old enough to know—and looking for perfection can lead you down a troubled path, as opposed to being around authentic friends, family, and lovers.

GIVENCHY jacket and skirt, GABRIELA HEARST pants, and CARTIER earrings, necklace, and rings.

And as a mother, and also a witness to youth culture and an up-and-coming generation, do you feel, or are you observing a similar sort of preoccupation with perfection? The big home run, lottery ticket hopes? Or do you find that, perhaps there’s a little bit more appreciation for measured growth?

Listen. I absolutely do. And I think it’s certainly this generation of teenagers and young adults right now who have witnessed the last several years politically, you know, for American kids, and globally, in terms of both the pandemic and our environment. Now they’re into, like, saving us from disaster, not looking for the unachievable perfection. They’re like, ‘Okay, how are we going to still have a home? How do we avoid school shootings? How do we get people to talk to each other? How do we finally create a world where racism isn’t leading every workplace environment choice, every case of police brutality.’ I mean, it’s just, they’re cleaning up a mess. They’re not fantasizing about a perfect future. And that’s heartbreaking. But it’s also realistic. They’re like, ‘You guys, you poisoned us. You poisoned the water supply, poisoned the ocean, poisoned the soil. You have created this disaster when it comes to our ozone layer. But now we’ve got to figure out: how do we fix this enough that we’re safe?’ They’re not running around going, Well, in two years, there’s never going to be another fire, another tornado, no sea level rise. I mean, they’re adopting sort of a survival mentality, not a dreamer mentality perhaps. That’s what I see.

In a culture so historically defined by dreaming, where do you see the potential adverse effects of that sort of hard-line realism, as opposed to idealism?

Well, I think if the whole world, right, as dreamers and the new generation of survivalists and realists came together and said, ‘You know what? Given the world order, consumerism can’t be part of the dream, guys. It doesn’t work. You don’t get your vacations, and your fossil fuels, and your dumping in the bay, and your using plastic because it’s easier, and, use it ’til you don’t want it anymore, and then get all new stuff.’ Right? That’s just not the world we live in, so we gotta build another dream. So, I think from their approach, hopefully the dreamers will still get to dream, but they’ll dream things like, ‘Oh my god, soil can save us. We have what we need—in terms of saving ourselves—and it’s right under our feet.’ And how exciting is that? That’s a new dream. Let’s get out there. Let’s plant, let’s create regenerative farms, let’s take on industrial farming and look at how to do this differently. What an exciting time to dream of a new way of providing the globe with food and resources, as opposed to, I want what’s mine, and I’m going to take it even if it means leaving everybody else out.

GIVENCHY jacket and skirt, GABRIELA HEARST pants, and CARTIER earrings, necklace, and rings.

So in a sense, the dreaming hasn’t ceased, it’s evolved, and it’s less about material sort of gain or amassing, but still the poetry and love and magic, so to speak, are alive and kicking in the young psyche.

Yeah. You know, my daughter loves her school she goes to. She goes to a wonderful school, fairly newly in the last couple of years. It’s not huge, and it doesn’t have the giant field, and it doesn’t have a million sports teams. Its emphasis isn’t about being a theatre school to the biggest Ivy League schools, its emphasis is on community, and kindness, and true diversity. Creating a community that looks like real life in a school environment, and treating teachers well and treating students well. She just loves it so much for those reasons, and I find that so moving, that she wanted to make a change, but she didn’t need all the bells and whistles. She just needed to feel safe, and safe for her was something that reflected the world as it is—not this protected, created world. You know what I’m saying?

To the tune of what you’ve been speaking about—this kind of broad stroke calamity on planet Earth—I came across a remark you’d made before, where you talk about finding kind of humor in broken places. It feels there aren’t little broken places anymore—the whole thing is broken. I was curious if you’re seeing that reflected in storytelling, and is there still sort of a desire to find granular stories? Or are you thinking there’s more energy dedicated to addressing these kinds of larger crises?

Yeah. I mean, I pray there’s room for both. I pray there’s room to take on massive stories in a granular way. Which I think Florian is doing, right? This massive theme of mental health in a raw, vulnerable, tender way. It’s just mind blowing to me. As is the exciting and amazing group of filmmakers—in both my mentors and people that I kind of grew up learning from—who are still doing extraordinary things and asking extraordinary questions, like say, from David Lynch to Steven Spielberg, all the way to this new generation of filmmakers. And there are filmmakers I don’t know that are definitely looking at it radically differently, like the Safdie brothers, who I think are really looking at fractured insecurity, and consumerism, and relationships. And they’re doing it as, before, like you mentioned, they’re looking for the humor, the irreverence in those places, which is why I feel so lucky to have worked with the group of people that I have gotten to work with thus far. Whether it be David or Alexander Payne, or Noah Baumbach, Greta Gerwig, Andrea Arnold, all the way to Mike White. They are all also looking for that balance. I just think it gives us insight into ourselves—it cracks the story open so that you can relate. And, you know, hopefully, even in the world of big commercial franchise films, you can find like-minded people who want to find the opportunity to tell something deeper about people, or about what’s going on on the planet, or relationships. And young filmmakers, thank God, and female storytellers more and more. That’s exciting.

CHLOÉ poncho.

You’re now in a position where you can offer mentorship on set. You’ve been in receipt of a lot of mentorship on set. What do you feel is something you have personally sought to pass on that you were in receipt of, as a mentor?

Well, with fellow actors, it’s a group effort. So whether you are the person who’s worked the most, or the newest actor, it doesn’t matter. You are there together to remind each other to be honest. To strip away any idea of how it’s supposed to be, or being performative, or looking for what the result should be. It’s a journey towards truth. There’s no right or wrong. And I would say that for all of us. I mean, the organism that is a movie crew is a group of people that come from their own family histories, and if you’re going to make a great film, we have to trust ourselves deeply. And if you’ve got a deeply insecure narcissist, or you’ve got someone who doesn’t feel their opinion matters, your movie goes down. You know what I mean? That’s been the greatest lesson to watch. It’s everyone equally respecting each other. And the great leaders, in the filmmaking, are the ones who make it a party for everybody. Of everyone I worked with, Robert Altman would be someone I put at the top of that list. Bob made it a party for everybody. Everybody came to Bailey’s every night, and it was always great food and a good time. He would see his set decorator or his prop master kind of stressing in their mind... a prop not seeming right, off the set kind of looking at it, but not saying a word, and he would go, ‘Wait, come here. What don’t you like? I see you don’t like something?’ And they’re like, ‘Well, if it were me, I don’t think that character would be reading a book. Like, he seems like a guy who hasn’t read a book in 20 years.’ And Bob was like, ‘Oh, my God, I didn’t catch that. Jesus Christ, I was gonna let that kid read a book... You’re so right.’ I mean, it takes this massive team to catch every moment for each other, and there’s no one more important. I mean that lesson was huge.

There’s a construct whereby everyone is capable of poisoning the well, but everyone’s also capable of creating a safe space, or a celebratory or a jubilant space?

Exactly, exactly. And I mean how to be outspoken, and ambitious and trusting of oneself with absolute humility is a lifelong journey. I can’t wait to get there. I’m just learning.

As you’re describing that kind of consummate positivity on set, you know, it brings to mind the theme of this issue, which is magic. And magic is a word that is, of course, bandied about showbiz. I wanted to ask how you might relate to the concept of magic? Is it that of spontaneity, or when everything kind of finds alignment?

Something unseen, something much larger than we know. That’s all magic to me. And magic is also effortlessness. When something feels so effortless. You know, a child at play, or Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in Swingtime—all things that feel so effortless are so magical.

CHLOÉdress.

And sometimes the irony that perhaps a lot of effort preceded the payoff?

Yes, exactly. And that you don’t see it. That moment is so beautiful. That’s magical.

Speaking of effort, I wanted to briefly touch on a remark you made in an interview previously about scenes that might not be shot today, or couldn’t be shot today, given their social volatility... let’s call it. Is that something you feel holds true for a lot of your work? Do you feel there were experimentations with power structures, or sexuality, or even violence that today might not see light because of a more complex social situation? Do you agree? Do you feel like those are only a handful in number? How do you relate to scenes you say might not be shot in, say, 2021?

Oh man. I feel like most things I’ve done, maybe. I think most things I’ve done. I think, rightly, everything is being reconsidered in terms of who deserves to have voice in storytelling. So I don’t know if a specific movie I’ve done with a male writer / director, with a lens toward a female, they might go, ‘Well, how does he know?’ I don’t know that exploring a man’s violence towards a woman... I think it’s considered very differently. It exists, and these are conversations—that’s part of art—but I don’t know if they get made, or in the same way, or with the same freedoms. Tragically, the first movie that actually comes to mind is actually Citizen Ruth. And Citizen Ruth needs to be made and seen as, like, required viewing right now in our country. It depicts so brilliantly the divide, and the lack of consideration for a pregnant woman and her own right to choose, and what that looks like, and all sides are divided. Everyone is a target, in a way, by Alexander Payne in that film, which I think is what’s brilliant about it. And it’s done with such incredible humor and irreverence. But, you know, does somebody give you the money to make that film right now? I mean I hope, I think everyone does, but I worry.

I cannot believe that we made a movie about the choice issue in the 90s. And that I think it would be hard to make now— that is just tragic. That is so tragic.

CHANEL blouse, THOM BROWNE skirt, CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN boots, and BVLGARI earrings and necklace.

That begs the question: have we reached a point in culture where even parody doesn’t have legs to stand on because of inequity or a historic poisoning of the well?

As journalists, artists, and filmmakers, we just have to keep exposing truth. That is our job. And however we do it, with humor, with fine art, with an interview, with a documentary, with music—more than ever before, we’ve got to get in the face of anything that still has blinders on. There’s a million ways to do it. We don’t have time to just not think about anything anymore. It’s unbelievable. Unbelievable times, right?

It’s a trip. This miraculous coalescence of nature and mankind’s deepest and darkest.

I remember the night that the President of the United States, and the First Lady and their daughters, came out of the White House to see a rainbow spectacle of light on the White House. Same-sex marriage was finally, after so many horrific years of injustice, was finally seen as truth and law and we were all celebrated. And like, how are we here? How did we reverse history? In a million ways. You know what I mean? That’s crazy to think about. Even for us, we’re like, ‘Well, it’s a little bit of progress.’ I mean, that was massive. It was massive. We didn’t know how massive it was. We were just pissed off we were having to finally celebrate then.

There was this pursuit for something that was never had, and then it was had, and then we came to see how easily it could be stripped away and stomped on. What can you tell me about the documentary you recently co-produced, The Way I See It, and how it relates to this pursuit of sharing of voice?

I mean, I definitely have to give credit to my producing partner, Jayme Lemons, who saw Pete Souza’s book tour, and we both loved his photographs, and the archivist he has been for this country through the Reagan years, as well as the Obama years. The moments he captured are so profound, and we really felt there was something here. And once we sat with Pete, and talked to him about it, he gave us a sense of commitment to the movie we wanted to make, the larger movie, which was: what does nobility and empathy and leadership look like, and it’s not a divide between right or left. It’s just about considering human beings and being their champion. That’s what was most exciting—that he was ready to join the team on that.

CHLOÉ dress.

Maybe we’re entering a space where the adored, or heard, or seen, are persons that aren’t courting the divide, but sort of ascending it. You remarked on how Florian’s set how kindness has been a key agent in the collaboration and creativity. I wanted to close on how you relate to the idea of kindness, and how that’s evolved over time, and why is it important to be kind?

Well, that’s magical. It shouldn’t have to be, but kindness is magic, because it makes magical things happen. And, you know, my mom, and my grandmother, they were always such generous people to everyone, and really thoughtful to offer a meal or something cool to drink to anyone, whoever, you know, a plumber who came to the house.... I think being raised and seeing that, and then when I was moved to a workplace environment, and being on set, and I would see people in leadership positions holding that kind of kindness—that really meant a lot to me. It’s just more fun. And by the way, it’s hard to be fearless with mean people. I just never understood, working as an actor working with mean people, and you’re in a place where you’re trying to do brave work, or boundary-less work... you know? It’s nice to know someone’s got your back. So that’s why when you find people who feel like family, and you’re lucky you get to work with them over and over again.

We always want to see kind and fun people again right? It’s in our nature.

Don’t we? Ugh, yeah! In a way, you kind of see all of it to know how to have an instinct about what real kindness looks like, or who to trust, and it’s a journey to believe in your own instincts about people, and know the difference of what feels kind to you, and how to be kind, even when you’re afraid.

Photographed by Yana Yatsuk Styled by Mui-Hai Chu Hair by Kylee Heath at A-Frame Agency Makeup by Pati Dubroff at Forward Artists Manicure by Kimmie Keyes at The Wall Group Style Assisting by Sky Barbarick & Justice Jackson Videography by Mynxii White Written by Matthew Bedard Location: The Mountain Mermaid, Topanga, CA