It’s like a palm frond aflame— swaying and spitting upward over the frosty brick facades. It’s Broadway, or Bleecker— downtown—not so sure. It’s February and it’s nearing 4am and Alex Cameron waves this beacon—this torch—coolly, cockily. It refuses to smolder. It orbs and it beckons. It calls out. It burns for me.

I approach and realize nothing’s aflame. Nothing’s burning. And I’m not even sure it’s Alex Cameron. This guy looks like him, but Cameron’s got a Joker-rich deck of identities spilling from his suit coat... each with a past, hangups, wiles. Not to mention his hair’s greased back, his transition lenses grading his dead eyes just so, and it’s hard to look at him without, in turn, looking at myself.

See, Alex Cameron is one of the finer pop musicians in the space. What’s unclear is whether the pop environs he occupies can actually cope with it. Whether they can—as Cameron compels—confront themselves in the mirror. Or if doing so is just a little too... dark? Too close to home?

So maybe the torch I’ve envisaged is just a song? The tortured and exultant hue of a man? Maybe these throbbing embers of an apparition are just that—the summoned ghosts of internal discord. The dogged halos of our actions and inactions heaving around after us?

See, Alex Cameron sings torch songs. But unlike the pained and suffering torches of convention and yore, the unrequited love that could be said to define the torch does not always associate with another human. Sometimes it’s Cameron himself. Emotional quests and defeats teased from their hibernation, their repression, by a songwriter committed to momenta, to mining meaning, and to occasionally suffocating it all into silence with extreme behavior. Where Cameron strays uniquely autonomous is that sometimes the torches go borderline berserk with joyous, sucrose-dripping melodiousness.

You see, nothing is lost on the world when artists tackle “dark” subject matter— drug use, sexual exploitation, self-harm, impotence, child neglect, depression, violence, The Cancel, The Deal, you name it—but the world is a bit lost when that tackling sounds like an air-brushed, dreamy 80s easy listener (is that a kettle drum? And saxophonist Roy Molloy’s name rhymes?)... that rattles around in your ear canal like 86 degree saltwater, stubbornly refusing a fervent slap and shake. It’s easy listening that ain’t easy.

And therein lies the splendor of Alex Cameron. Through his interwinding ambitions to voice different characters across different social strata and disposition, the musician forges a taut tenderness between emotional dissonance and idealism. Between longing and resignation. Between humor and hard, cold facts. Oh, and he can belt it like a motherfucker.

I spend a bit of time with the modest, Bondi Beach, Australia-born musician in New York and LA before he alights with his bandmates to Europe to tour his new record, Oxy Music (Secretly Canadian)—his fourth studio effort. We have some chuckles, sure. But what strikes me about the guy, besides his toothy sartorial impulses, is his enthusiasm—a rarity, unfortunately, in the entertainment milieu—for what others have to say. And perhaps even more meaningfully so: what some might be hoping to say.

And the sparkle. A mischievousness that no doubt enjoys the spoils of the stage, and the carousel of people a relentlessly touring musician has the privilege to encounter. Here, then, is a conversation with Alex Cameron on the nuances of one of America’s universal issues, the imperative of keeping it moving and growing, and the decadence and dynamism of a great pair of transition lenses.

CALVIN KLEIN tank, SAINT LAURENT BY ANTHONY VACCARELLO pants, talent’s own shoes and rings, NINNA YORK earrings and rings, and PR SOLO Private Archive crown.

I was in Europe for fashion weeks, and despite there being some reservation hanging in the air about the next phases of COVID—not to mention we’ve now a fucking war on, which is like a dark cloud over everything—the atmosphere felt pretty receptive to culture, eager to get bouncing. Are you looking forward to your tour?

I’ve slowly trained myself not to get my hopes up—to the point of stoicism—when it comes to work opportunities. I’m starting to be able to flex that muscle. I think it’s an important lesson to save the celebration for once the job’s done. That’s about all we can do right now: wish the best to other bands touring, hope they’re doing the same for us, and stick our heads down and try to get as much work done as possible.

And what would you attribute to the fortification of that muscle? Would you call it repeated failures, or witnessing others? Mentorship? Where do you feel you’ve honed that skill? I think it has to be experienced. A lot of people in the music business were implying that it was gonna be a tough road. But more than a tough one—I think it’s a long one. The people that we are exposed to—by the media, musical charts, and pop music, generally—are these supposed wonder kids who just happened to write some hit songs in their bedrooms. But if someone’s breaking into the mainstream at 16-years- old, it’s because their parents were in show business and have been pushing them since they were six-years-old. No one flukes into this.

And you at 16?

I started playing drums in bands when I was about 16, and didn’t start writing my own songs until I was about 24/25. I’ve now been at it for the better part of a decade, and I’ve been lucky in that I never necessarily feel ready for success. Because of the grind, and the pattern that so many opportunities come and go. Some come to fruition and others just pass by you like an empty, out-of-service train. All I can do is turn up and work.

DIOR MEN jacket, BAZAAR TYLER top, and stylist’s own earrings.

There’s no likening this decade to any other, right? What about this last de- cade, in which you’ve made your mark, has been favorable to that? What are the favorable conditions for Alex Cameron?

I heard a lot of songwriters and writers and actors complaining—not complaining, discussing—cancel culture and identity politics as perhaps being shackles on the potential creative process. But the more nuanced the cultural discussion is, the more access to ideas I have. That never really scared me, because I’ve always been under the impression that the market decides whether or not an artist gets to work. So the idea of an audience turning on me—because of my art—was always a bit... if that happened, that wouldn’t be something I could control anyway. So I’m not going to not do what I do in my songs because of potential backlash. Ideally, people would be more focused on being good people outside of their work, as opposed to being worried about whether their work was going to hurt them in some way.

Were you observing backlash in other artists’ output or content?

It was never the stories and the ideas that people were concerned about.They were concerned about violent, danger- ous behavior.When we’re talking about the #MeToo movement, we’re talking about how show business was domi- nated by powerful, angry, violent men for so long—and I’m sure, to a certain extent, absolutely, still is. I think that was probably the moment that I started to feel really confident in the idea that as long as my songs were informed by my own earnestness and genuine desire to explore what might be considered the underbelly or the lesser-told stories in the form of songwriting... each of my records I really enjoyed writing because of the cultural discussion around them. Because I think about it so much. I think those years were the ones that shaped me the most. I wrote these songs—I think we put out Forced Witness—and maybe the Harvey Weinstein story broke a couple of months later in 2017. It’s an indication that, as an artist I was, I dunno, telling a story that was real. And that’s really what I care about—clarity, and trying to get a sense of what it is to be a person in this time.

Where do you personally struggle with earnestness? I feel like our—let’s call it ‘heightened’—cultural literacy can sometimes cloud sincerity, maybe ob- fuscate that sincere arrow, if you will, or the piercing of the arrow. How do you stay sincere?

My songs are really poppy and anthe- mic and melodically quite pretty, just because that’s what’s going on in my head. I think that the fact that I move quite naturally towards upbeat, almost celebratory sounds, keeps me in check. Because if I were to write a lyric that maybe wasn’t so focused on a character, or a world that I wasn’t really concerned with building, the whole thing would go out the window.

How do you relate that to the humor that is often consistent in your records?

I think that even though there are certainly elements of humor in my writing, I really do feel that if I write something that makes me laugh, I’m mostly laughing because it’s true, which is the anchor of comedy, generally. I certainly don’t set out to write funny songs. They’re all very earnest to me, but I do use irony, no doubt, in the character voicing and things like that. It’s all dialogue to me, really. I write conversations.

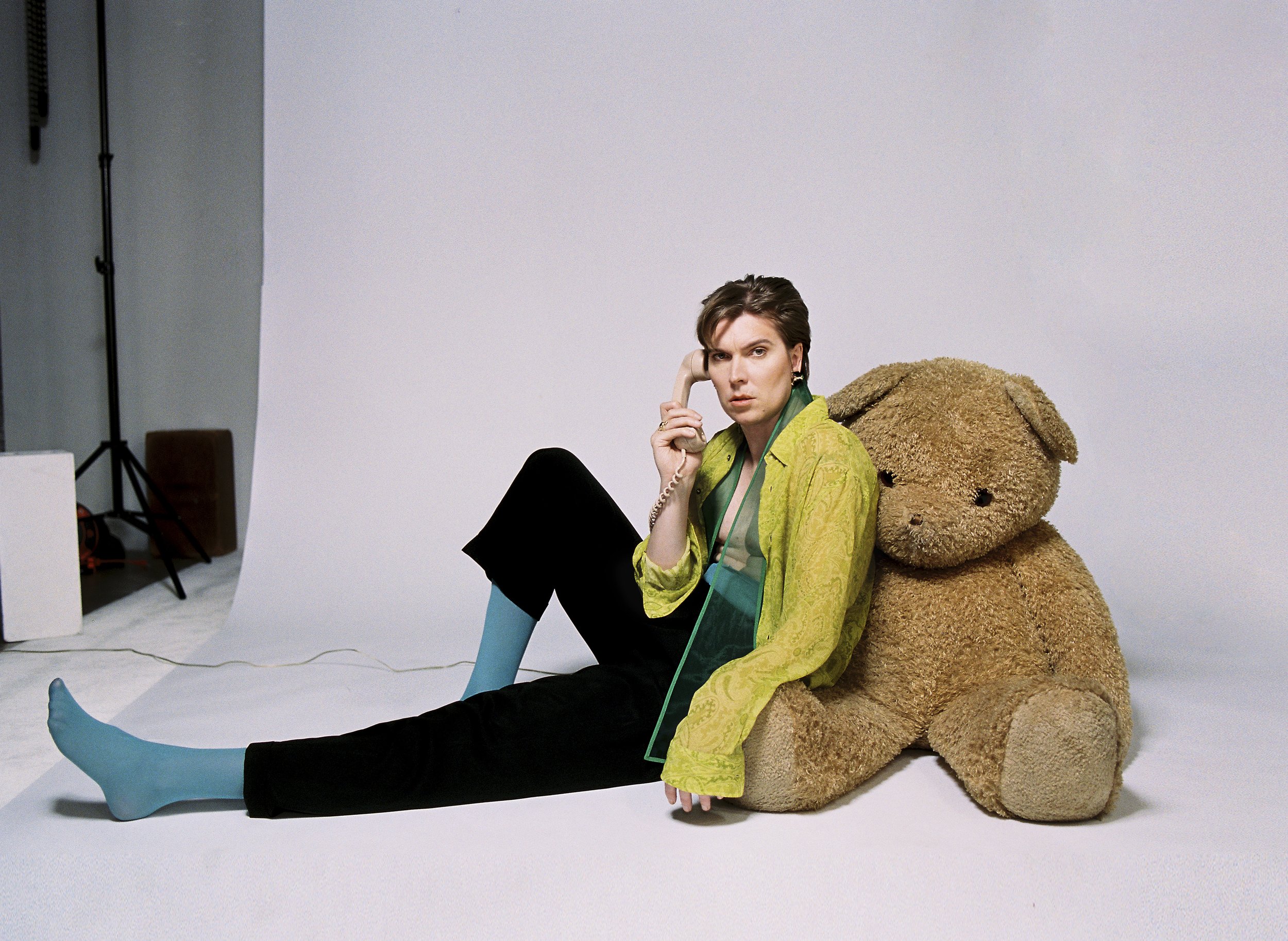

ETRO shirt, GIORGIO ARMANI pants, stylist’s own tights and earrings, ALIONA KONONOVA scarf, and talent’s own ring.

You’re almost shaking your head at the fact that things are how they are?

Yeah, I think there’s certainly a self-awareness there. That’s one aspect I do enjoy—the unreliable narrator who is unwittingly revealing their own obliviousness.

Oxy Music, it might be said, features a tension between the album’s dark subject matter and the otherwise poppy, joyous, upbeat sonics and production—a tension perhaps demonstrative of drug use. The music sounds like the drug feels—or at the very least, its onset. How might you describe this tension within the album?

When I’m doing an unreliable narrator— and certainly a drug-addled mind is unreliable, at least in my experience—and when I’m choosing a certain sound, or writing a certain melody or progression, there has to be a DNA where, to the onlooker, it’s obviously confusion... but to the person experiencing it, it’s confidence and bravado, and even an attempt at emotional earnestness. That might be working for the person communicating it, but for the people hearing or experiencing it, it commonly isn’t received that way. I always really like to try, if I’m writing a character, to make the music that that character would make. Take the song “Oxy Music,” which is essentially someone wrestling with denial. I wanted to make an upbeat, danceable pop song to represent the idea that ‘All I’m doing is keeping the party going, and what’s the harm in that?’ My friend Kai, who mixed the record, described it as ‘crying while dancing’, and I really liked that as a description. It’s sort of like this sadness on the dance floor.

And do you feel like, with an arguably more drug-themed effort, that there stands to be a lack of compassion in audience reception? Because drug use gets in the way of compassion very often.

No doubt. And I think that you might have found the reason that I wanted to write the record. People act like it’s not a cultural problem, or a problem for humanity, they act like it’s a problem for very specific people. But it is, as far as I can tell—outside of the socioeconomic statistics and reasons for drug and substance abuse—it does affect everyone. Even just as an idea it affects people. All you have to do is see the common response from communities when it’s discovered that someone is abusing drugs. I would like to think that the more evolved response is to act with compassion and understanding. I think the whole reprimanding someone for using drugs—they’re already beating themselves up enough.You guys don’t have to jump in.

Oxy Music obviously invokes the opioid crisis, which is killing and has killed so many people. You’ve been a NewYorker for a long time, but you are from a different culture, and I think people are perhaps looking at the opioid crisis from around the world as just another symptom of crumbling empire. What’s your perspective on what’s going on?

I was here in New York when—I saw it happen—people started saying ‘Shit, I think my dealer’s giving me fentanyl.’ When that started happening, things started to get a lot more complex than the more common OD. Because people would take the amount of drugs they were used to taking, and it was all of the sudden a fatal dose. There’s nothing more the Australian government would love than to privatize all education, and all hospital care, and healthcare. Australia is sort of this really impressionable little cousin that just loves the big cousin so much and just wants to do everything the big cousin does. Obviously, there are some major differences between America and Australia, but the only difference between Australia and America when it comes to fentanyl is availability. And I don’t doubt that it is probably making its way there slowly.

I wanted to talk about the word ‘toxic.’ Earlier, you referenced the systemic monstrosities that we’ve all become very accustomed to in culture. I’ve seen responses to your songwriting suggesting there are implications of ‘toxic masculinity’ or your wrestling with that in culture. You have ‘toxic’ as an adjective—so someone’s behaving ‘toxically’. But you also have ‘toxic’ as a noun—a toxin that might interact with something non-toxic. I wonder, where has your trajectory experienced that interactivity? Where is the push/pull there?

I remember someone telling me that a weed is just any plant growing where it shouldn’t be growing. It’s a broad term; it’s not a specific type of plant necessarily. So I guess the same could be said about a toxin. It’s just something that is present where it ideally wouldn’t be. And it might have negative effects on the good that’s trying to be done, or the sustenance that’s trying to be maintained.

When it comes to men and the identity of the male... I grew up by the beach, which was so physique-obsessed, and physical appearance was basically the currency. Perhaps growing up around that, and playing a lot of sport, and always having my physique referenced—that I looked like a girl or, ‘How come I wasn’t putting on weight? Why wasn’t I filling out?’ Beyond that, there were things like very, very casual racism, and a deep understanding that things are a certain way and they shouldn’t change—and I’ve always really liked change. I’ve always thought that progress is peaceful and that it takes violence to keep things a certain way. Things change naturally, but to try and keep something—or to harken back to a time—that takes violence. I’ve always thought that’s where war comes from—this desperation to try and revive a naturally dying culture. I mean, ‘naturally dying culture’ in terms of cultural evolution—not in terms of stomped-out cultures from war, or colonialism, or things like that.

What was your relationship like to media at that time?

I think that, in my formative years, I was really not a deeply political kid. Once I was taught about the corporate nature of news, I got a certain understanding to take broadcast news with a dash of salt. And later, just seeing myself as a kid, and reflecting back on those years, and how much I bought into it. It was very important to me—this appearance thing. Even if you disagree with it, it becomes the rules. Once I was able to properly observe that in myself, I think I’ve never really looked back. So, I think, in a lot of ways I probably felt like a toxin as a kid and in my younger years. Just being out of place and always wanting something else. And then once I started playing in bands and touring... every now and then I’d find someone that I really liked, and really got along with, and realized there were much more important things than even what I thought about myself, you know?

Yes, there’s a point where what begins as the interactivity with the toxin becomes toxic, and it does ask questions about education. It does become about exposure and experience. Do you have a memory that comes to mind that catalyzed that release—maybe the observation of other artists, or seeing a piece of cinema, or even something familial?

I remember seeing The King of Comedy— the Scorsese film with Robert De Niro— and definitely feeling something click in my mind. At that point I’d already started—I was probably in my early twenties when I saw that movie—I’d started writing poems and songs, and I started to see it more in literature and movies. Sort of like this oblivious character that is so unaware of their own very obvious faults, you know? And that was probably a moment where I stopped even trusting my own ideas, and just stopped giving myself so much credit for everything, and started to see things as more of a pursuit of looking and finding, as opposed to taking credit for creating. And certainly, I think, spending more and more time just with women, and a more diverse group of people—once I started traveling and seeing the countries and how the things that were important to certain people changed from city to city. Then I started appreciating how insignificant the things I thought were so culturally important were.

Vintage bodysuit, socks, and braided necklace, DIOR MEN pants, NINNA YORK necklace and rings, and PR SOLO Private Archive glove.

Would you say that connects to the ‘long road’ you mentioned regarding the music world?

Yeah, I think I have this inherent distrust of anyone that is overly confident in what they are. And I certainly have a massive distrust in anyone who says that they know who I am. I just call bullshit, because I’m not really interested in someone who’s confident in who they are. I get life goals and passions and things like that.

I understand those things, and how you have to be confident in them, no doubt. But when it comes down to—honestly, even beliefs—I’m just an open book, really. A good idea is a good idea and a bad idea is a bad idea, and those things can change. You know, a bad idea last year might be a good idea in five years.

This idea of confidence and what others think is certainly invoked on the opening track, “Best Life.” This cultural compression to really be something online, someone projecting that unbridled confidence. Can you kind of speak to that idea in the context of that song?

Certainly, when it comes to social media and technology... let’s say you’re working in a lab, or for a firm that’s designing a computer. It takes hours of solitude, and trial and error, and an understanding of systems and science and mathematics. And these are very solitary pursuits. This is a certain profession that can mold someone into being somewhat of a social hermit. Then you start talking about the fact that, well, these are the people that are designing the ways that we communicate with one another. So the idea that it’s called social media is kind of ridiculous because it’s made by people who don’t really get to socialize. And that’s a generalization, but I think it’s an important observation as well.

Like this notion of ‘interaction’ is flawed from the outset?

The way that we’re encouraged to communicate and interact with one another—I don’t like the word ‘interaction.’ I don’t like what it’s become. Interaction, at its core, is a very beautiful word, but it’s been turned into a way to represent statistics and cultural clout. I also think back to when I was really doing all the music management work myself—the amount of times I would check my email. It’s like, if I were to be checking my letterbox that much a hundred years ago, I’d be an insane person.

In relation to self-projection on the internet—it brings up this notion of ‘persona’. In reading a bit about you, it’s a popular word that crops up when describing your creative output, your song-writing. And yet it doesn’t feel like Alex Cameron is portending a persona so much as refusing to be static or fixed. Are you in agreement? Do you feel like that word gets used sometimes in a misunderstood capacity, or is a little easy?

I think it’s maybe the simplest way of describing—it’s a very broad term. I feel like it’s a little confusing for me, because I feel most like myself when I’m writing. Even if I’m writing in a voice that’s distant from mine. I am as close as I could possibly be to understanding myself when I’m performing. So the idea that I’m becoming other people when I’m writing or performing doesn’t feel totally apt. I think I broadcast perspectives more than characters. I try and amplify them in a way that doesn’t necessarily—in the words of it—either condemn or support. It’s just calling it how it is and letting other people decide. That would be ideal for me.

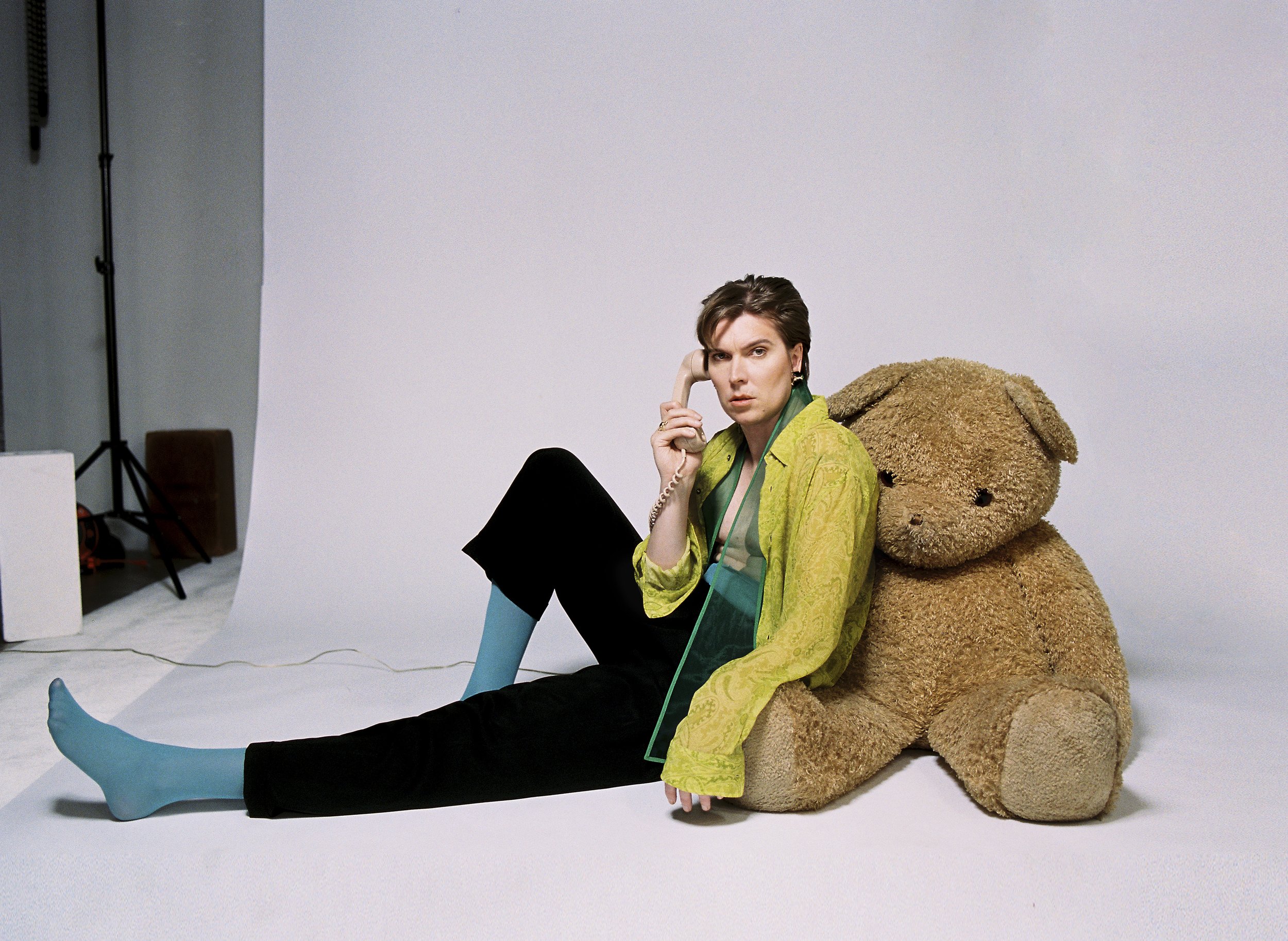

Vintage bathing suit, stylist’s own tights, and LEISURE SOCIETY glasses

The theme of this issue is “Phone a Friend”—which of course pays homage to the more old school ways of communicating, but also this idea of calling on people in times of need. And I think when you mentioned that your opinions aren’t important to you, but perhaps those of others are? As you age and become more evolved, is your relationship to reaching out, or needing that sort of support system, as relevant as it once was? Has it ever been?

When I’m doing bad, it’s not about advice, it’s about being present and almost reminding me that the world keeps spinning and life keeps going—what could easily be called a distraction. I need to see change around me to believe in change and to believe that I can change, so really, I think phoning a friend, for me, and getting support, is just a matter of knowing that my dear friends are there no matter what. I would describe that as a reminder that even though I’m struggling—whether it’s with depression, or my mental health, or with substances, or a massive life change, or financially, you know, you name it—my best friends know to give me advice when I’m doing well.

Describe a particular experience in the creation of this record or a particular song that there was a lesson learned or an interesting takeaway.

There was one night where we were working on a track, it’s called “Prescription Refill,” and we had the instrumental in the melody. I had a mattress—we went to IKEA and bought these mattresses to sleep on—and we’d turned the lights off, it was dark, and we were laying there and Juice (Justin Nijssen, bandmate and songwriter) was like, ‘Don’t you think transition lenses are just, like, the most absurd thing?’ And we were talking about it and laughing hysterically, about these people we’d come across in our life that were wearing transition lenses. And what started as a very funny thing sort of became very serious, because whoever this is we’re writing about should be trying to convince someone that his glasses aren’t necessarily transition lenses because of the sun—it’s more an indication of how he’s feeling. It’s his mood. I mean, I’ve got like a deep love for transition lenses. I just think it’s like such a bold look. I got up and stumbled over to the keyboard and was just playing around with the words. And then it all of a sudden became Check out my transition lenses, girl / They show you how this boy is feeling... And then the song just started. It just exploded. That was really important, because then I started to understand the whole album and who we were talking about. I’m talking about people who have made very bold decisions, and are incorporating it into their identity, and slowly becoming aware that the cracks are obvious to everyone else.

That awakening inside the wormhole—when the lucidity or euphoria is running thin, right?

It’s like digging a hole and giving yourself a week to do it. And after you’ve had a few goes with the shovel, you realize the tunnel has already been built, and you’re just in it. You’re walking around freely.

And as you mentioned, drug use in culture has such wider implications—invoking very human experiences like denial, or compulsion, or secrecy, or glamor... are all a part of it. And perhaps that’s where there is a sort of universality?

You know, experiencing addiction is a very pure, instinctual thing. All of a sudden your thoughts don’t matter—it’s only your feelings. You become so obsessed with how you feel and, ‘What do I need to do to make myself feel okay?’ It’s all feeling, there’s no thought, it’s all instinct. It’s very intense, you know? And I think that’s maybe one of the reasons I wrote the record—to sort of indicate or suggest that we’re talking about instincts here and not necessarily conscious decisions.

Photographed by Max Montgomery Styled by Tiffani Rae Makeup: Nathan Hejl Hair: Candice Birns at Statement Artists Flaunt Film Director: Matilda Montgomery Written by Matthew Bedard

It’s like a palm frond aflame— swaying and spitting upward over the frosty brick facades. It’s Broadway, or Bleecker— downtown—not so sure. It’s February and it’s nearing 4am and Alex Cameron waves this beacon—this torch—coolly, cockily. It refuses to smolder. It orbs and it beckons. It calls out. It burns for me.

I approach and realize nothing’s aflame. Nothing’s burning. And I’m not even sure it’s Alex Cameron. This guy looks like him, but Cameron’s got a Joker-rich deck of identities spilling from his suit coat... each with a past, hangups, wiles. Not to mention his hair’s greased back, his transition lenses grading his dead eyes just so, and it’s hard to look at him without, in turn, looking at myself.

See, Alex Cameron is one of the finer pop musicians in the space. What’s unclear is whether the pop environs he occupies can actually cope with it. Whether they can—as Cameron compels—confront themselves in the mirror. Or if doing so is just a little too... dark? Too close to home?

So maybe the torch I’ve envisaged is just a song? The tortured and exultant hue of a man? Maybe these throbbing embers of an apparition are just that—the summoned ghosts of internal discord. The dogged halos of our actions and inactions heaving around after us?

See, Alex Cameron sings torch songs. But unlike the pained and suffering torches of convention and yore, the unrequited love that could be said to define the torch does not always associate with another human. Sometimes it’s Cameron himself. Emotional quests and defeats teased from their hibernation, their repression, by a songwriter committed to momenta, to mining meaning, and to occasionally suffocating it all into silence with extreme behavior. Where Cameron strays uniquely autonomous is that sometimes the torches go borderline berserk with joyous, sucrose-dripping melodiousness.

You see, nothing is lost on the world when artists tackle “dark” subject matter— drug use, sexual exploitation, self-harm, impotence, child neglect, depression, violence, The Cancel, The Deal, you name it—but the world is a bit lost when that tackling sounds like an air-brushed, dreamy 80s easy listener (is that a kettle drum? And saxophonist Roy Molloy’s name rhymes?)... that rattles around in your ear canal like 86 degree saltwater, stubbornly refusing a fervent slap and shake. It’s easy listening that ain’t easy.

And therein lies the splendor of Alex Cameron. Through his interwinding ambitions to voice different characters across different social strata and disposition, the musician forges a taut tenderness between emotional dissonance and idealism. Between longing and resignation. Between humor and hard, cold facts. Oh, and he can belt it like a motherfucker.

I spend a bit of time with the modest, Bondi Beach, Australia-born musician in New York and LA before he alights with his bandmates to Europe to tour his new record, Oxy Music (Secretly Canadian)—his fourth studio effort. We have some chuckles, sure. But what strikes me about the guy, besides his toothy sartorial impulses, is his enthusiasm—a rarity, unfortunately, in the entertainment milieu—for what others have to say. And perhaps even more meaningfully so: what some might be hoping to say.

And the sparkle. A mischievousness that no doubt enjoys the spoils of the stage, and the carousel of people a relentlessly touring musician has the privilege to encounter. Here, then, is a conversation with Alex Cameron on the nuances of one of America’s universal issues, the imperative of keeping it moving and growing, and the decadence and dynamism of a great pair of transition lenses.

CALVIN KLEIN tank, SAINT LAURENT BY ANTHONY VACCARELLO pants, talent’s own shoes and rings, NINNA YORK earrings and rings, and PR SOLO Private Archive crown.

I was in Europe for fashion weeks, and despite there being some reservation hanging in the air about the next phases of COVID—not to mention we’ve now a fucking war on, which is like a dark cloud over everything—the atmosphere felt pretty receptive to culture, eager to get bouncing. Are you looking forward to your tour?

I’ve slowly trained myself not to get my hopes up—to the point of stoicism—when it comes to work opportunities. I’m starting to be able to flex that muscle. I think it’s an important lesson to save the celebration for once the job’s done. That’s about all we can do right now: wish the best to other bands touring, hope they’re doing the same for us, and stick our heads down and try to get as much work done as possible.

And what would you attribute to the fortification of that muscle? Would you call it repeated failures, or witnessing others? Mentorship? Where do you feel you’ve honed that skill? I think it has to be experienced. A lot of people in the music business were implying that it was gonna be a tough road. But more than a tough one—I think it’s a long one. The people that we are exposed to—by the media, musical charts, and pop music, generally—are these supposed wonder kids who just happened to write some hit songs in their bedrooms. But if someone’s breaking into the mainstream at 16-years- old, it’s because their parents were in show business and have been pushing them since they were six-years-old. No one flukes into this.

And you at 16?

I started playing drums in bands when I was about 16, and didn’t start writing my own songs until I was about 24/25. I’ve now been at it for the better part of a decade, and I’ve been lucky in that I never necessarily feel ready for success. Because of the grind, and the pattern that so many opportunities come and go. Some come to fruition and others just pass by you like an empty, out-of-service train. All I can do is turn up and work.

DIOR MEN jacket, BAZAAR TYLER top, and stylist’s own earrings.

There’s no likening this decade to any other, right? What about this last de- cade, in which you’ve made your mark, has been favorable to that? What are the favorable conditions for Alex Cameron?

I heard a lot of songwriters and writers and actors complaining—not complaining, discussing—cancel culture and identity politics as perhaps being shackles on the potential creative process. But the more nuanced the cultural discussion is, the more access to ideas I have. That never really scared me, because I’ve always been under the impression that the market decides whether or not an artist gets to work. So the idea of an audience turning on me—because of my art—was always a bit... if that happened, that wouldn’t be something I could control anyway. So I’m not going to not do what I do in my songs because of potential backlash. Ideally, people would be more focused on being good people outside of their work, as opposed to being worried about whether their work was going to hurt them in some way.

Were you observing backlash in other artists’ output or content?

It was never the stories and the ideas that people were concerned about.They were concerned about violent, danger- ous behavior.When we’re talking about the #MeToo movement, we’re talking about how show business was domi- nated by powerful, angry, violent men for so long—and I’m sure, to a certain extent, absolutely, still is. I think that was probably the moment that I started to feel really confident in the idea that as long as my songs were informed by my own earnestness and genuine desire to explore what might be considered the underbelly or the lesser-told stories in the form of songwriting... each of my records I really enjoyed writing because of the cultural discussion around them. Because I think about it so much. I think those years were the ones that shaped me the most. I wrote these songs—I think we put out Forced Witness—and maybe the Harvey Weinstein story broke a couple of months later in 2017. It’s an indication that, as an artist I was, I dunno, telling a story that was real. And that’s really what I care about—clarity, and trying to get a sense of what it is to be a person in this time.

Where do you personally struggle with earnestness? I feel like our—let’s call it ‘heightened’—cultural literacy can sometimes cloud sincerity, maybe ob- fuscate that sincere arrow, if you will, or the piercing of the arrow. How do you stay sincere?

My songs are really poppy and anthe- mic and melodically quite pretty, just because that’s what’s going on in my head. I think that the fact that I move quite naturally towards upbeat, almost celebratory sounds, keeps me in check. Because if I were to write a lyric that maybe wasn’t so focused on a character, or a world that I wasn’t really concerned with building, the whole thing would go out the window.

How do you relate that to the humor that is often consistent in your records?

I think that even though there are certainly elements of humor in my writing, I really do feel that if I write something that makes me laugh, I’m mostly laughing because it’s true, which is the anchor of comedy, generally. I certainly don’t set out to write funny songs. They’re all very earnest to me, but I do use irony, no doubt, in the character voicing and things like that. It’s all dialogue to me, really. I write conversations.

ETRO shirt, GIORGIO ARMANI pants, stylist’s own tights and earrings, ALIONA KONONOVA scarf, and talent’s own ring.

You’re almost shaking your head at the fact that things are how they are?

Yeah, I think there’s certainly a self-awareness there. That’s one aspect I do enjoy—the unreliable narrator who is unwittingly revealing their own obliviousness.

Oxy Music, it might be said, features a tension between the album’s dark subject matter and the otherwise poppy, joyous, upbeat sonics and production—a tension perhaps demonstrative of drug use. The music sounds like the drug feels—or at the very least, its onset. How might you describe this tension within the album?

When I’m doing an unreliable narrator— and certainly a drug-addled mind is unreliable, at least in my experience—and when I’m choosing a certain sound, or writing a certain melody or progression, there has to be a DNA where, to the onlooker, it’s obviously confusion... but to the person experiencing it, it’s confidence and bravado, and even an attempt at emotional earnestness. That might be working for the person communicating it, but for the people hearing or experiencing it, it commonly isn’t received that way. I always really like to try, if I’m writing a character, to make the music that that character would make. Take the song “Oxy Music,” which is essentially someone wrestling with denial. I wanted to make an upbeat, danceable pop song to represent the idea that ‘All I’m doing is keeping the party going, and what’s the harm in that?’ My friend Kai, who mixed the record, described it as ‘crying while dancing’, and I really liked that as a description. It’s sort of like this sadness on the dance floor.

And do you feel like, with an arguably more drug-themed effort, that there stands to be a lack of compassion in audience reception? Because drug use gets in the way of compassion very often.

No doubt. And I think that you might have found the reason that I wanted to write the record. People act like it’s not a cultural problem, or a problem for humanity, they act like it’s a problem for very specific people. But it is, as far as I can tell—outside of the socioeconomic statistics and reasons for drug and substance abuse—it does affect everyone. Even just as an idea it affects people. All you have to do is see the common response from communities when it’s discovered that someone is abusing drugs. I would like to think that the more evolved response is to act with compassion and understanding. I think the whole reprimanding someone for using drugs—they’re already beating themselves up enough.You guys don’t have to jump in.

Oxy Music obviously invokes the opioid crisis, which is killing and has killed so many people. You’ve been a NewYorker for a long time, but you are from a different culture, and I think people are perhaps looking at the opioid crisis from around the world as just another symptom of crumbling empire. What’s your perspective on what’s going on?

I was here in New York when—I saw it happen—people started saying ‘Shit, I think my dealer’s giving me fentanyl.’ When that started happening, things started to get a lot more complex than the more common OD. Because people would take the amount of drugs they were used to taking, and it was all of the sudden a fatal dose. There’s nothing more the Australian government would love than to privatize all education, and all hospital care, and healthcare. Australia is sort of this really impressionable little cousin that just loves the big cousin so much and just wants to do everything the big cousin does. Obviously, there are some major differences between America and Australia, but the only difference between Australia and America when it comes to fentanyl is availability. And I don’t doubt that it is probably making its way there slowly.

I wanted to talk about the word ‘toxic.’ Earlier, you referenced the systemic monstrosities that we’ve all become very accustomed to in culture. I’ve seen responses to your songwriting suggesting there are implications of ‘toxic masculinity’ or your wrestling with that in culture. You have ‘toxic’ as an adjective—so someone’s behaving ‘toxically’. But you also have ‘toxic’ as a noun—a toxin that might interact with something non-toxic. I wonder, where has your trajectory experienced that interactivity? Where is the push/pull there?

I remember someone telling me that a weed is just any plant growing where it shouldn’t be growing. It’s a broad term; it’s not a specific type of plant necessarily. So I guess the same could be said about a toxin. It’s just something that is present where it ideally wouldn’t be. And it might have negative effects on the good that’s trying to be done, or the sustenance that’s trying to be maintained.

When it comes to men and the identity of the male... I grew up by the beach, which was so physique-obsessed, and physical appearance was basically the currency. Perhaps growing up around that, and playing a lot of sport, and always having my physique referenced—that I looked like a girl or, ‘How come I wasn’t putting on weight? Why wasn’t I filling out?’ Beyond that, there were things like very, very casual racism, and a deep understanding that things are a certain way and they shouldn’t change—and I’ve always really liked change. I’ve always thought that progress is peaceful and that it takes violence to keep things a certain way. Things change naturally, but to try and keep something—or to harken back to a time—that takes violence. I’ve always thought that’s where war comes from—this desperation to try and revive a naturally dying culture. I mean, ‘naturally dying culture’ in terms of cultural evolution—not in terms of stomped-out cultures from war, or colonialism, or things like that.

What was your relationship like to media at that time?

I think that, in my formative years, I was really not a deeply political kid. Once I was taught about the corporate nature of news, I got a certain understanding to take broadcast news with a dash of salt. And later, just seeing myself as a kid, and reflecting back on those years, and how much I bought into it. It was very important to me—this appearance thing. Even if you disagree with it, it becomes the rules. Once I was able to properly observe that in myself, I think I’ve never really looked back. So, I think, in a lot of ways I probably felt like a toxin as a kid and in my younger years. Just being out of place and always wanting something else. And then once I started playing in bands and touring... every now and then I’d find someone that I really liked, and really got along with, and realized there were much more important things than even what I thought about myself, you know?

Yes, there’s a point where what begins as the interactivity with the toxin becomes toxic, and it does ask questions about education. It does become about exposure and experience. Do you have a memory that comes to mind that catalyzed that release—maybe the observation of other artists, or seeing a piece of cinema, or even something familial?

I remember seeing The King of Comedy— the Scorsese film with Robert De Niro— and definitely feeling something click in my mind. At that point I’d already started—I was probably in my early twenties when I saw that movie—I’d started writing poems and songs, and I started to see it more in literature and movies. Sort of like this oblivious character that is so unaware of their own very obvious faults, you know? And that was probably a moment where I stopped even trusting my own ideas, and just stopped giving myself so much credit for everything, and started to see things as more of a pursuit of looking and finding, as opposed to taking credit for creating. And certainly, I think, spending more and more time just with women, and a more diverse group of people—once I started traveling and seeing the countries and how the things that were important to certain people changed from city to city. Then I started appreciating how insignificant the things I thought were so culturally important were.

Vintage bodysuit, socks, and braided necklace, DIOR MEN pants, NINNA YORK necklace and rings, and PR SOLO Private Archive glove.

Would you say that connects to the ‘long road’ you mentioned regarding the music world?

Yeah, I think I have this inherent distrust of anyone that is overly confident in what they are. And I certainly have a massive distrust in anyone who says that they know who I am. I just call bullshit, because I’m not really interested in someone who’s confident in who they are. I get life goals and passions and things like that.

I understand those things, and how you have to be confident in them, no doubt. But when it comes down to—honestly, even beliefs—I’m just an open book, really. A good idea is a good idea and a bad idea is a bad idea, and those things can change. You know, a bad idea last year might be a good idea in five years.

This idea of confidence and what others think is certainly invoked on the opening track, “Best Life.” This cultural compression to really be something online, someone projecting that unbridled confidence. Can you kind of speak to that idea in the context of that song?

Certainly, when it comes to social media and technology... let’s say you’re working in a lab, or for a firm that’s designing a computer. It takes hours of solitude, and trial and error, and an understanding of systems and science and mathematics. And these are very solitary pursuits. This is a certain profession that can mold someone into being somewhat of a social hermit. Then you start talking about the fact that, well, these are the people that are designing the ways that we communicate with one another. So the idea that it’s called social media is kind of ridiculous because it’s made by people who don’t really get to socialize. And that’s a generalization, but I think it’s an important observation as well.

Like this notion of ‘interaction’ is flawed from the outset?

The way that we’re encouraged to communicate and interact with one another—I don’t like the word ‘interaction.’ I don’t like what it’s become. Interaction, at its core, is a very beautiful word, but it’s been turned into a way to represent statistics and cultural clout. I also think back to when I was really doing all the music management work myself—the amount of times I would check my email. It’s like, if I were to be checking my letterbox that much a hundred years ago, I’d be an insane person.

In relation to self-projection on the internet—it brings up this notion of ‘persona’. In reading a bit about you, it’s a popular word that crops up when describing your creative output, your song-writing. And yet it doesn’t feel like Alex Cameron is portending a persona so much as refusing to be static or fixed. Are you in agreement? Do you feel like that word gets used sometimes in a misunderstood capacity, or is a little easy?

I think it’s maybe the simplest way of describing—it’s a very broad term. I feel like it’s a little confusing for me, because I feel most like myself when I’m writing. Even if I’m writing in a voice that’s distant from mine. I am as close as I could possibly be to understanding myself when I’m performing. So the idea that I’m becoming other people when I’m writing or performing doesn’t feel totally apt. I think I broadcast perspectives more than characters. I try and amplify them in a way that doesn’t necessarily—in the words of it—either condemn or support. It’s just calling it how it is and letting other people decide. That would be ideal for me.

Vintage bathing suit, stylist’s own tights, and LEISURE SOCIETY glasses

The theme of this issue is “Phone a Friend”—which of course pays homage to the more old school ways of communicating, but also this idea of calling on people in times of need. And I think when you mentioned that your opinions aren’t important to you, but perhaps those of others are? As you age and become more evolved, is your relationship to reaching out, or needing that sort of support system, as relevant as it once was? Has it ever been?

When I’m doing bad, it’s not about advice, it’s about being present and almost reminding me that the world keeps spinning and life keeps going—what could easily be called a distraction. I need to see change around me to believe in change and to believe that I can change, so really, I think phoning a friend, for me, and getting support, is just a matter of knowing that my dear friends are there no matter what. I would describe that as a reminder that even though I’m struggling—whether it’s with depression, or my mental health, or with substances, or a massive life change, or financially, you know, you name it—my best friends know to give me advice when I’m doing well.

Describe a particular experience in the creation of this record or a particular song that there was a lesson learned or an interesting takeaway.

There was one night where we were working on a track, it’s called “Prescription Refill,” and we had the instrumental in the melody. I had a mattress—we went to IKEA and bought these mattresses to sleep on—and we’d turned the lights off, it was dark, and we were laying there and Juice (Justin Nijssen, bandmate and songwriter) was like, ‘Don’t you think transition lenses are just, like, the most absurd thing?’ And we were talking about it and laughing hysterically, about these people we’d come across in our life that were wearing transition lenses. And what started as a very funny thing sort of became very serious, because whoever this is we’re writing about should be trying to convince someone that his glasses aren’t necessarily transition lenses because of the sun—it’s more an indication of how he’s feeling. It’s his mood. I mean, I’ve got like a deep love for transition lenses. I just think it’s like such a bold look. I got up and stumbled over to the keyboard and was just playing around with the words. And then it all of a sudden became Check out my transition lenses, girl / They show you how this boy is feeling... And then the song just started. It just exploded. That was really important, because then I started to understand the whole album and who we were talking about. I’m talking about people who have made very bold decisions, and are incorporating it into their identity, and slowly becoming aware that the cracks are obvious to everyone else.

That awakening inside the wormhole—when the lucidity or euphoria is running thin, right?

It’s like digging a hole and giving yourself a week to do it. And after you’ve had a few goes with the shovel, you realize the tunnel has already been built, and you’re just in it. You’re walking around freely.

And as you mentioned, drug use in culture has such wider implications—invoking very human experiences like denial, or compulsion, or secrecy, or glamor... are all a part of it. And perhaps that’s where there is a sort of universality?

You know, experiencing addiction is a very pure, instinctual thing. All of a sudden your thoughts don’t matter—it’s only your feelings. You become so obsessed with how you feel and, ‘What do I need to do to make myself feel okay?’ It’s all feeling, there’s no thought, it’s all instinct. It’s very intense, you know? And I think that’s maybe one of the reasons I wrote the record—to sort of indicate or suggest that we’re talking about instincts here and not necessarily conscious decisions.

Photographed by Max Montgomery Styled by Tiffani Rae Makeup: Nathan Hejl Hair: Candice Birns at Statement Artists Flaunt Film Director: Matilda Montgomery Written by Matthew Bedard