Satin nylon jacket and cotton ankle-length pants with sheer silk nylon overlay by Hood By Air and Leather harness boots by The Frye Company.

Cotton shirt coat with zippers and Cotton drawstring pants with logo by Hood By Air.

Leather jacket with attached mandarin collar vest and Leather shorts with knee-zippered pockets by Hood By Air and Leather lace-up Earthkeepers 6-inch boots by Timberland.

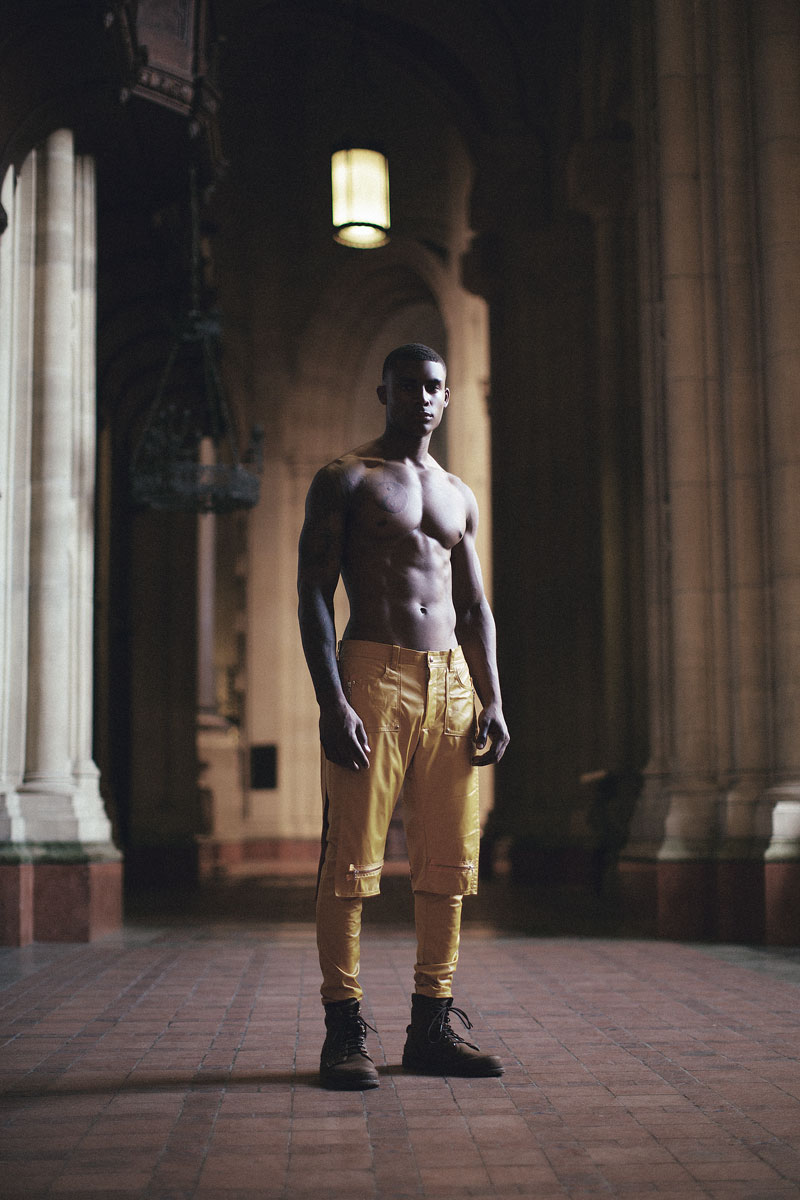

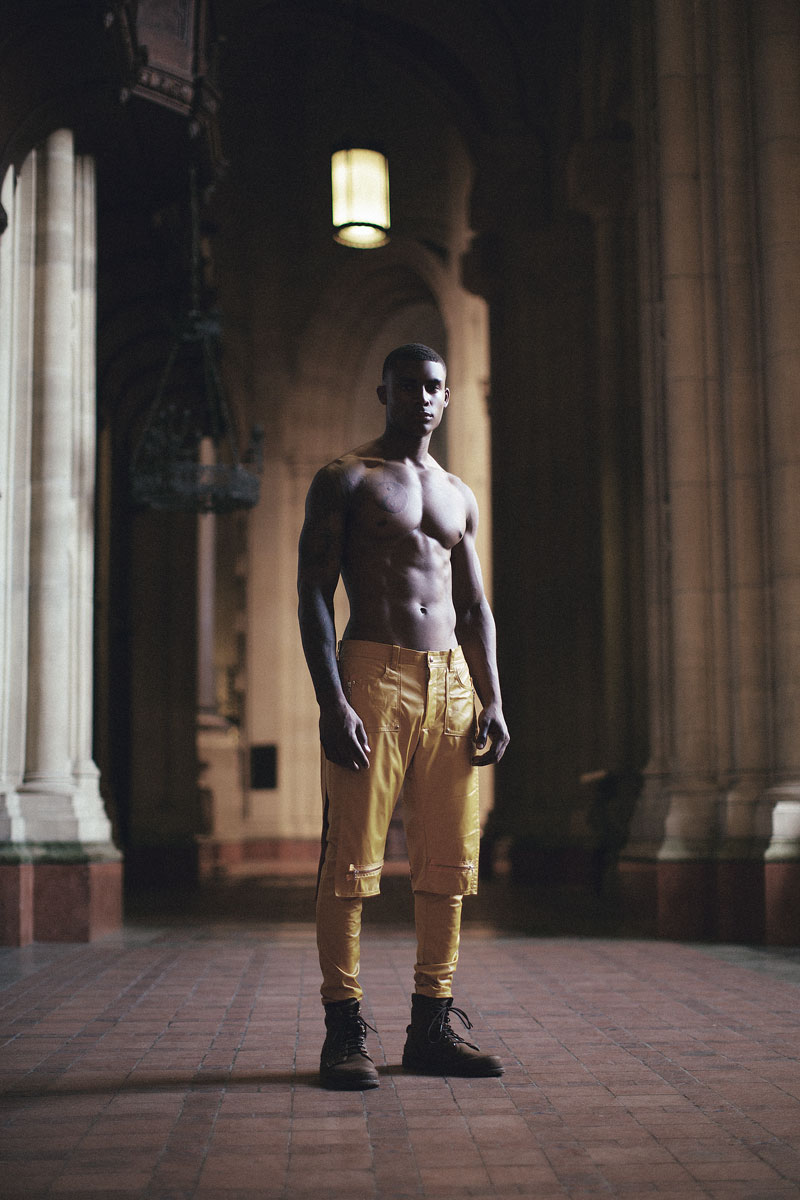

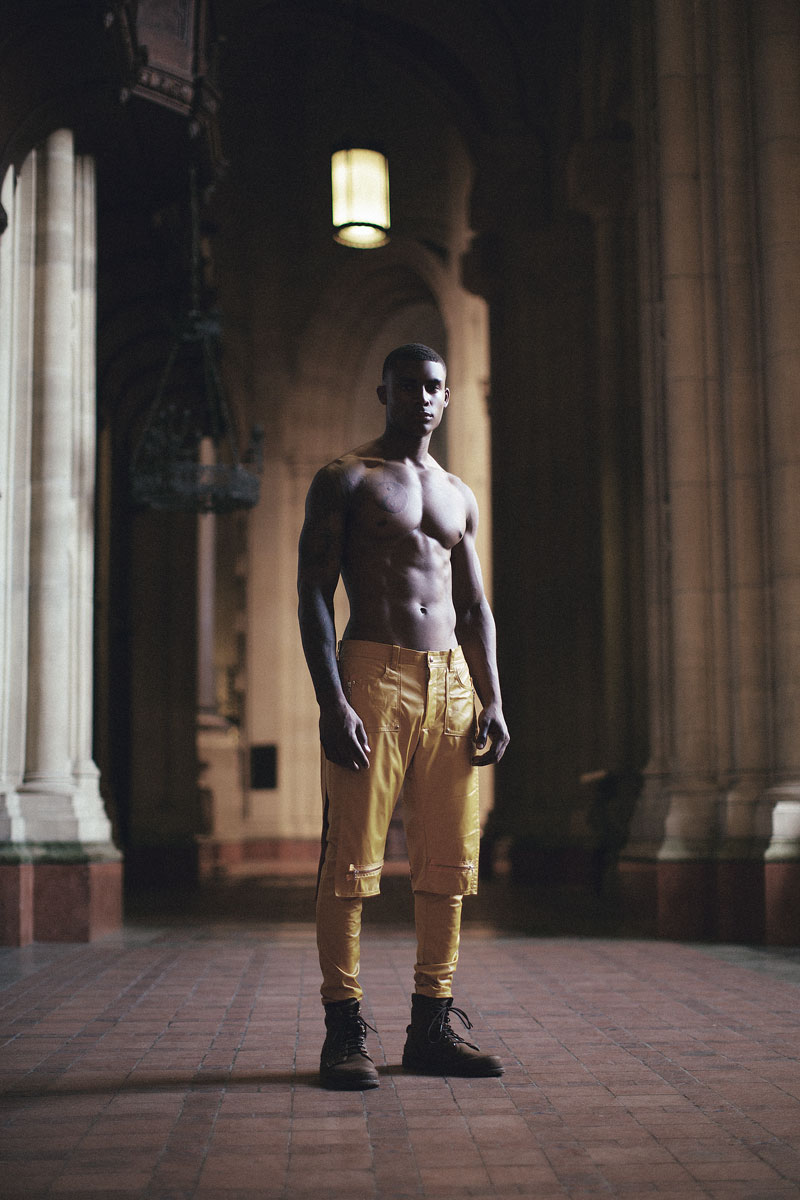

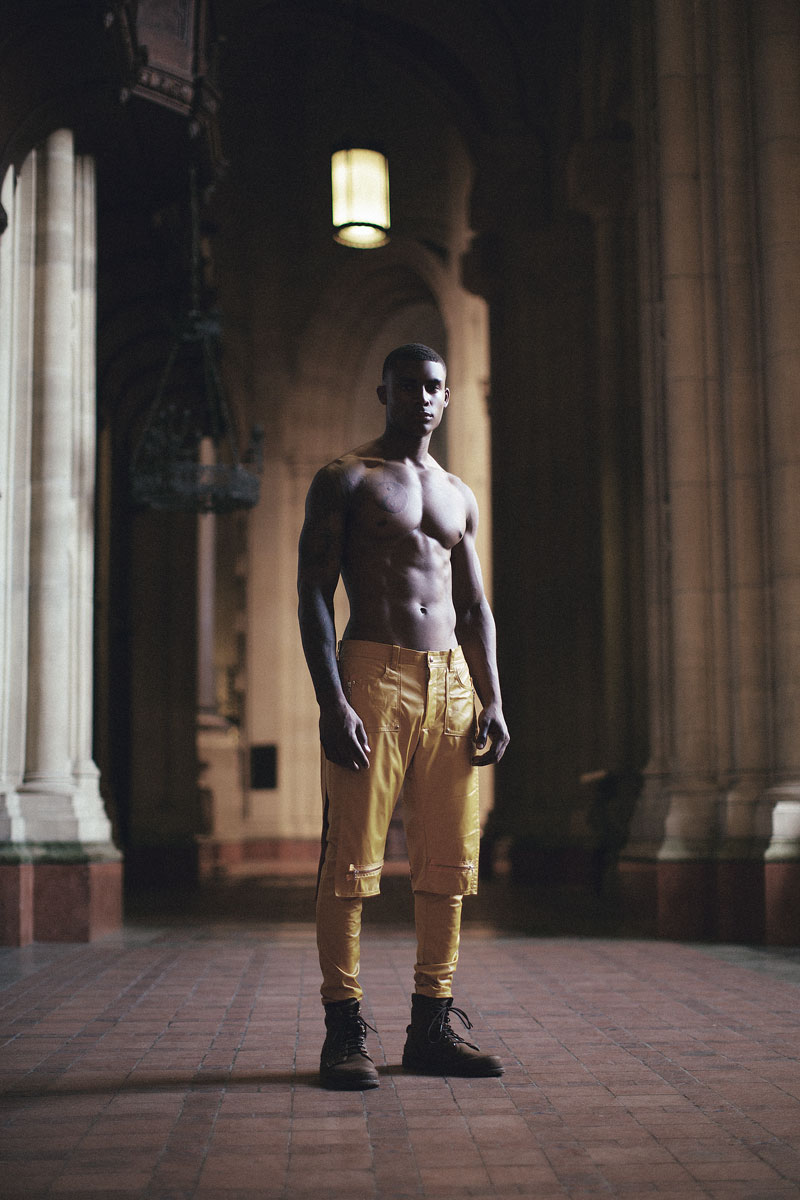

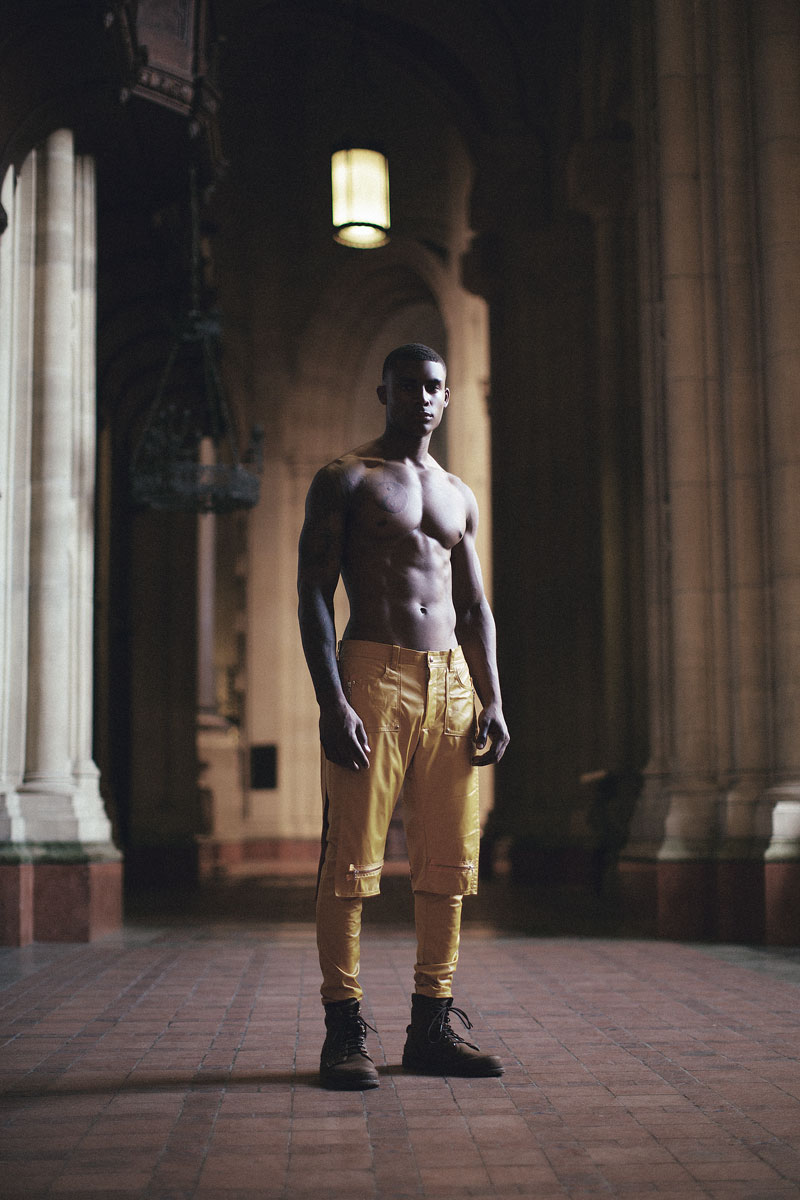

Leather short pants with side zippers and knee pockets by Hood By Air and Leather lace-up Earthkeepers 6-inch boots by Timberland.

Shayne Oliver photographed in Harlem, N.Y. in July 2013.

Leather crewneck jacket with shoulder and elbow zippers and Cotton drawstring sweatpants with upper thigh zippers by Hood By Air.

Cotton long sleeve logo t-shirt by Hood By Air.

Leather puffer coat with asymmetrical zipper by Hood By Air.

Hood By Air Fall/Winter 2013

“I work for my own Pleasure.” “Oh, come on, Don't be Selfish.”

Garments are composed of certain rigid structures that, despite their seemingly infinite possibility of variations—shorter here, longer there, higher armholes, tighter or looser lines—limit the fashion designer’s ability to offer a sense of newness each season.

Nonetheless, a designer can sniff out the undercurrents of the socio-cultural zeitgeist and coalesce those sentiments into a collection that epitomizes a newness, the present moment where the tumult of underground fashion, music, and art commingle.

Cue New York Fashion Week, Fall 2013. Midnight blue flashes on vertically installed neon LED lights at the end of the platform, scarcely making a quick paced silhouette visible. White lights suddenly beam onto the figure, revealing a shiny black leather down jacket with sweat sleeves, leather sleeve gloves, a black logo sweatshirt, a second black sweatshirt wrapped around the waist in lieu of shorts, and black leggings that reveal just a hint of upper thigh.

For those unfamiliar with the scene, that presentation took place at the Hood By Air (HBA) show at Milk Studios. An array of looks from the show encompassed classic staples in designer Shayne Oliver’s fashion vocabulary. By placing equal emphasis on street and design beyond the rigid contours of masculine-feminine, HBA transforms into appealing wardrobes that often feel beyond mere sporty or designer wares.

With his characteristically loose approach, Oliver, 25, often breaks sartorial gender rules, nonchalantly combining different elements into one outfit; for example, dropped waist denim pants with zippers on the upper thigh that convert into shorts, worn under white shorts. These basic street wear designs, including T-shirts and sweatshirts branded with giant logos and prints, juxtapose with avant-garde ‘downtown’ elements; midriff tops and sheer nylon overlaying sweatpants instill an overt sexual prowess onto otherwise coarse athletic street wear.

Oliver’s interest in fashion developed organically, “I was always playing around with clothes, especially my own clothes,” the designer says, fresh from a trip scouting denim production resources in Los Angeles. “I lived with my grandmother, who was a seamstress in Trinidad, until I was about eleven years old. When I came back to live with my mother in East New York, everyone that I saw was wearing all kinds of T-shirts and sweatshirts. I wanted to make the T-shirts that I wore a bit different by ripping them, re-sewing, and spray-painting them.”

As his craft evolved, his business sense followed, if not without a few missteps. “I started to make my own clothes—and make clothes that I wanted to sell—right out of high school. I knew what I wanted to do but I was very naïve. When I first started, I would make a few items and I would take them to stores and try to sell them. I had no idea how the fashion system worked. I decided to switch to FIT \[Fashion Institute of Technology\] from a fine arts school.” Even then, he was restless; he dropped out of FIT in 2006. “I started to realize that lifestyle was much more important, specifically in New York. I looked around where I lived, what was around me, and the circle of friends I had at the time—the downtown kids and the outer borough kids.”

Understandably, his maturation in New York, specifically Brooklyn, is a constant source of inspiration for the streetwear aspects of his designs. Even so, it gradually becomes clear that his avant-garde leanings can also be traced back to the borough. “Jay Z and Roc-A-Fella culture pretty much ran Brooklyn. It was the height of the hip-hop era where street style and expensive fashion were kings. But underneath, there were kids who would wear Dior Homme by Hedi Slimane—it was rare because it was early on in 2002. I didn’t even know exactly what Dior Homme was at the time.” He continues, “The early aughts were a crazy period in Brooklyn and I was just absorbing what was around me.”

Outside of powerhouses McQueen and Gaultier in the ’80s, further influences for Oliver appear to be homegrown. “I started to go out and I was hanging out with the homothug kids. That culture was about taking street clothes to another level, but allowing them to still remain street clothes.” Ah, homothug, a word one doesn’t hear often in 2013. As with many subcultures it can be hard to pin down its collapse. “It’s crazy right? I don’t know \[when it happened\] but it just vanished. Maybe the failing economy was part of its demise, too. But ‘homothug’ was losing its identity because so many kids wanted to imitate it \[that\] it wasn’t authentic anymore. It was very clique-y toward the end. When the kids who originate the look know it’s over, then you know it’s done.”

Oliver’s first offerings in 2006 were light in construction. “I started to do slogan T-shirts. I didn’t really start with a brand or anything—I was just printing things and experimenting with T-shirts and sweatshirts, then moving on to more clothing items.” That began to change for the designer in 2007. “I started to experiment with cutting and sewing. I would take a sweatshirt and reconfigure it and then I start to think about doing it from scratch, like making patterns for them. The first ‘collection’ so to speak, was around mid-2008.”

That fall collection, ‘Higher Learning,’ contained black sweatshirts with cutout inside sleeves, a black and gray windbreaker with black knee shorts, a black knee tee-dress with white prints, and black shorts with black tights and slim sweat tops. There were black fluid embroidered dress shirts and white “Realness” logo tee-dresses worn with nylon cropped coats. In this—his first “real” season—the parameters that would define the designer’s aesthetic began to emerge.

From there, with the help of a production partner, Oliver began to explore more complex techniques, experimenting with pleating and zippers until 2009, when his collections abruptly stopped. “My production manager was leaving the country and I wasn’t able to complete the new collection. At the time I was DJing at events with Venus X \[of GHE20G0TH1K\] to help finance the collection, so I had to stop until mid-2011.” The break may have become a necessary gap in the designer’s creative process. “I took the time that I was doing DJ gigs to think about how to reconfigure things, how it all works together, and how to reemerge.”

His comeback in 2011 came after that two-year hiatus, when the designer was able to scrape together funds for a presentation. “It wasn’t a collection, I was just putting a lot of different concepts out there—nothing cohesive just a bunch of ideas. I wanted to come back with different elements that would be coming soon.”

The show was a varied offering: gray tight sweatpants with a front skirt panel and long back train; a gray wool jacket with suspenders serving as button closures, paired with white cotton asymmetric shorts with one flared leg. A mixed cast of models wore re-appropriated UFO pants with tight doo-rags on their heads, walking around the small loft in white or black thigh high socks and old Jack Purcells modified into slippers. That evening’s gathering downtown was a quiet explosion far from fashion’s mainstream. From there, HBA began to regain its foothold within popular culture. Most recently, rapper A$AP Rocky closed the Fall 2013 show, prowling down the runway in a charcoal neoprene slim logo coat and black capri pants, cementing HBA’s current status among diverse urban performers and audiences.

His current production expansion is quiet and gradual with each move carefully considered. He notes that his pace is intentional, as he proceeds with HBA’s resurrection “slowly and in an organic way.” His pieces are currently available at Opening Ceremony and VFiles in New York, Colette in Paris, online retailers like RSVP Gallery, Selfridges, and Harvey Nichols in London. Not bad for a designer peddling wares that can be a bit tougher to swallow than your average high street knock-offs. Oliver is quick to remind us, “There are kids who want to present themselves just a little bit ‘off’ from the mainstream street look.” Oliver is one of those kids, and as the originator of his own subculture, it appears he has its identity confidently in check.

_Photographer_: Aram Bedrossian for Factorydowntown.com, New York. _Associate Fashion Editor_: ZaQuan Champ. _Models_: Manny Cruz, Eric Ramos, and Taejahn Taylor for Requestmodels.com, New York.

Grooming Notes: Repairing Moisturizer Emulsion by Dior Homme and Pure Abundance Volumizing Hair Spray by Aveda.

Satin nylon jacket and cotton ankle-length pants with sheer silk nylon overlay by Hood By Air and Leather harness boots by The Frye Company.

Satin nylon jacket and cotton ankle-length pants with sheer silk nylon overlay by Hood By Air and Leather harness boots by The Frye Company.

Cotton shirt coat with zippers and Cotton drawstring pants with logo by Hood By Air.

Cotton shirt coat with zippers and Cotton drawstring pants with logo by Hood By Air.

Leather jacket with attached mandarin collar vest and Leather shorts with knee-zippered pockets by Hood By Air and Leather lace-up Earthkeepers 6-inch boots by Timberland.

Leather jacket with attached mandarin collar vest and Leather shorts with knee-zippered pockets by Hood By Air and Leather lace-up Earthkeepers 6-inch boots by Timberland.

Leather short pants with side zippers and knee pockets by Hood By Air and Leather lace-up Earthkeepers 6-inch boots by Timberland.

Leather short pants with side zippers and knee pockets by Hood By Air and Leather lace-up Earthkeepers 6-inch boots by Timberland.

Shayne Oliver photographed in Harlem, N.Y. in July 2013.

Shayne Oliver photographed in Harlem, N.Y. in July 2013.

Leather crewneck jacket with shoulder and elbow zippers and Cotton drawstring sweatpants with upper thigh zippers by Hood By Air.

Leather crewneck jacket with shoulder and elbow zippers and Cotton drawstring sweatpants with upper thigh zippers by Hood By Air.

Cotton long sleeve logo t-shirt by Hood By Air.

Cotton long sleeve logo t-shirt by Hood By Air.

Leather puffer coat with asymmetrical zipper by Hood By Air.

Hood By Air Fall/Winter 2013

“I work for my own Pleasure.” “Oh, come on, Don't be Selfish.”

Garments are composed of certain rigid structures that, despite their seemingly infinite possibility of variations—shorter here, longer there, higher armholes, tighter or looser lines—limit the fashion designer’s ability to offer a sense of newness each season.

Nonetheless, a designer can sniff out the undercurrents of the socio-cultural zeitgeist and coalesce those sentiments into a collection that epitomizes a newness, the present moment where the tumult of underground fashion, music, and art commingle.

Cue New York Fashion Week, Fall 2013. Midnight blue flashes on vertically installed neon LED lights at the end of the platform, scarcely making a quick paced silhouette visible. White lights suddenly beam onto the figure, revealing a shiny black leather down jacket with sweat sleeves, leather sleeve gloves, a black logo sweatshirt, a second black sweatshirt wrapped around the waist in lieu of shorts, and black leggings that reveal just a hint of upper thigh.

For those unfamiliar with the scene, that presentation took place at the Hood By Air (HBA) show at Milk Studios. An array of looks from the show encompassed classic staples in designer Shayne Oliver’s fashion vocabulary. By placing equal emphasis on street and design beyond the rigid contours of masculine-feminine, HBA transforms into appealing wardrobes that often feel beyond mere sporty or designer wares.

With his characteristically loose approach, Oliver, 25, often breaks sartorial gender rules, nonchalantly combining different elements into one outfit; for example, dropped waist denim pants with zippers on the upper thigh that convert into shorts, worn under white shorts. These basic street wear designs, including T-shirts and sweatshirts branded with giant logos and prints, juxtapose with avant-garde ‘downtown’ elements; midriff tops and sheer nylon overlaying sweatpants instill an overt sexual prowess onto otherwise coarse athletic street wear.

Oliver’s interest in fashion developed organically, “I was always playing around with clothes, especially my own clothes,” the designer says, fresh from a trip scouting denim production resources in Los Angeles. “I lived with my grandmother, who was a seamstress in Trinidad, until I was about eleven years old. When I came back to live with my mother in East New York, everyone that I saw was wearing all kinds of T-shirts and sweatshirts. I wanted to make the T-shirts that I wore a bit different by ripping them, re-sewing, and spray-painting them.”

As his craft evolved, his business sense followed, if not without a few missteps. “I started to make my own clothes—and make clothes that I wanted to sell—right out of high school. I knew what I wanted to do but I was very naïve. When I first started, I would make a few items and I would take them to stores and try to sell them. I had no idea how the fashion system worked. I decided to switch to FIT \[Fashion Institute of Technology\] from a fine arts school.” Even then, he was restless; he dropped out of FIT in 2006. “I started to realize that lifestyle was much more important, specifically in New York. I looked around where I lived, what was around me, and the circle of friends I had at the time—the downtown kids and the outer borough kids.”

Understandably, his maturation in New York, specifically Brooklyn, is a constant source of inspiration for the streetwear aspects of his designs. Even so, it gradually becomes clear that his avant-garde leanings can also be traced back to the borough. “Jay Z and Roc-A-Fella culture pretty much ran Brooklyn. It was the height of the hip-hop era where street style and expensive fashion were kings. But underneath, there were kids who would wear Dior Homme by Hedi Slimane—it was rare because it was early on in 2002. I didn’t even know exactly what Dior Homme was at the time.” He continues, “The early aughts were a crazy period in Brooklyn and I was just absorbing what was around me.”

Outside of powerhouses McQueen and Gaultier in the ’80s, further influences for Oliver appear to be homegrown. “I started to go out and I was hanging out with the homothug kids. That culture was about taking street clothes to another level, but allowing them to still remain street clothes.” Ah, homothug, a word one doesn’t hear often in 2013. As with many subcultures it can be hard to pin down its collapse. “It’s crazy right? I don’t know \[when it happened\] but it just vanished. Maybe the failing economy was part of its demise, too. But ‘homothug’ was losing its identity because so many kids wanted to imitate it \[that\] it wasn’t authentic anymore. It was very clique-y toward the end. When the kids who originate the look know it’s over, then you know it’s done.”

Oliver’s first offerings in 2006 were light in construction. “I started to do slogan T-shirts. I didn’t really start with a brand or anything—I was just printing things and experimenting with T-shirts and sweatshirts, then moving on to more clothing items.” That began to change for the designer in 2007. “I started to experiment with cutting and sewing. I would take a sweatshirt and reconfigure it and then I start to think about doing it from scratch, like making patterns for them. The first ‘collection’ so to speak, was around mid-2008.”

That fall collection, ‘Higher Learning,’ contained black sweatshirts with cutout inside sleeves, a black and gray windbreaker with black knee shorts, a black knee tee-dress with white prints, and black shorts with black tights and slim sweat tops. There were black fluid embroidered dress shirts and white “Realness” logo tee-dresses worn with nylon cropped coats. In this—his first “real” season—the parameters that would define the designer’s aesthetic began to emerge.

From there, with the help of a production partner, Oliver began to explore more complex techniques, experimenting with pleating and zippers until 2009, when his collections abruptly stopped. “My production manager was leaving the country and I wasn’t able to complete the new collection. At the time I was DJing at events with Venus X \[of GHE20G0TH1K\] to help finance the collection, so I had to stop until mid-2011.” The break may have become a necessary gap in the designer’s creative process. “I took the time that I was doing DJ gigs to think about how to reconfigure things, how it all works together, and how to reemerge.”

His comeback in 2011 came after that two-year hiatus, when the designer was able to scrape together funds for a presentation. “It wasn’t a collection, I was just putting a lot of different concepts out there—nothing cohesive just a bunch of ideas. I wanted to come back with different elements that would be coming soon.”

The show was a varied offering: gray tight sweatpants with a front skirt panel and long back train; a gray wool jacket with suspenders serving as button closures, paired with white cotton asymmetric shorts with one flared leg. A mixed cast of models wore re-appropriated UFO pants with tight doo-rags on their heads, walking around the small loft in white or black thigh high socks and old Jack Purcells modified into slippers. That evening’s gathering downtown was a quiet explosion far from fashion’s mainstream. From there, HBA began to regain its foothold within popular culture. Most recently, rapper A$AP Rocky closed the Fall 2013 show, prowling down the runway in a charcoal neoprene slim logo coat and black capri pants, cementing HBA’s current status among diverse urban performers and audiences.

His current production expansion is quiet and gradual with each move carefully considered. He notes that his pace is intentional, as he proceeds with HBA’s resurrection “slowly and in an organic way.” His pieces are currently available at Opening Ceremony and VFiles in New York, Colette in Paris, online retailers like RSVP Gallery, Selfridges, and Harvey Nichols in London. Not bad for a designer peddling wares that can be a bit tougher to swallow than your average high street knock-offs. Oliver is quick to remind us, “There are kids who want to present themselves just a little bit ‘off’ from the mainstream street look.” Oliver is one of those kids, and as the originator of his own subculture, it appears he has its identity confidently in check.

_Photographer_: Aram Bedrossian for Factorydowntown.com, New York. _Associate Fashion Editor_: ZaQuan Champ. _Models_: Manny Cruz, Eric Ramos, and Taejahn Taylor for Requestmodels.com, New York.

Grooming Notes: Repairing Moisturizer Emulsion by Dior Homme and Pure Abundance Volumizing Hair Spray by Aveda.

Leather puffer coat with asymmetrical zipper by Hood By Air.

Hood By Air Fall/Winter 2013

“I work for my own Pleasure.” “Oh, come on, Don't be Selfish.”

Garments are composed of certain rigid structures that, despite their seemingly infinite possibility of variations—shorter here, longer there, higher armholes, tighter or looser lines—limit the fashion designer’s ability to offer a sense of newness each season.

Nonetheless, a designer can sniff out the undercurrents of the socio-cultural zeitgeist and coalesce those sentiments into a collection that epitomizes a newness, the present moment where the tumult of underground fashion, music, and art commingle.

Cue New York Fashion Week, Fall 2013. Midnight blue flashes on vertically installed neon LED lights at the end of the platform, scarcely making a quick paced silhouette visible. White lights suddenly beam onto the figure, revealing a shiny black leather down jacket with sweat sleeves, leather sleeve gloves, a black logo sweatshirt, a second black sweatshirt wrapped around the waist in lieu of shorts, and black leggings that reveal just a hint of upper thigh.

For those unfamiliar with the scene, that presentation took place at the Hood By Air (HBA) show at Milk Studios. An array of looks from the show encompassed classic staples in designer Shayne Oliver’s fashion vocabulary. By placing equal emphasis on street and design beyond the rigid contours of masculine-feminine, HBA transforms into appealing wardrobes that often feel beyond mere sporty or designer wares.

With his characteristically loose approach, Oliver, 25, often breaks sartorial gender rules, nonchalantly combining different elements into one outfit; for example, dropped waist denim pants with zippers on the upper thigh that convert into shorts, worn under white shorts. These basic street wear designs, including T-shirts and sweatshirts branded with giant logos and prints, juxtapose with avant-garde ‘downtown’ elements; midriff tops and sheer nylon overlaying sweatpants instill an overt sexual prowess onto otherwise coarse athletic street wear.

Oliver’s interest in fashion developed organically, “I was always playing around with clothes, especially my own clothes,” the designer says, fresh from a trip scouting denim production resources in Los Angeles. “I lived with my grandmother, who was a seamstress in Trinidad, until I was about eleven years old. When I came back to live with my mother in East New York, everyone that I saw was wearing all kinds of T-shirts and sweatshirts. I wanted to make the T-shirts that I wore a bit different by ripping them, re-sewing, and spray-painting them.”

As his craft evolved, his business sense followed, if not without a few missteps. “I started to make my own clothes—and make clothes that I wanted to sell—right out of high school. I knew what I wanted to do but I was very naïve. When I first started, I would make a few items and I would take them to stores and try to sell them. I had no idea how the fashion system worked. I decided to switch to FIT \[Fashion Institute of Technology\] from a fine arts school.” Even then, he was restless; he dropped out of FIT in 2006. “I started to realize that lifestyle was much more important, specifically in New York. I looked around where I lived, what was around me, and the circle of friends I had at the time—the downtown kids and the outer borough kids.”

Understandably, his maturation in New York, specifically Brooklyn, is a constant source of inspiration for the streetwear aspects of his designs. Even so, it gradually becomes clear that his avant-garde leanings can also be traced back to the borough. “Jay Z and Roc-A-Fella culture pretty much ran Brooklyn. It was the height of the hip-hop era where street style and expensive fashion were kings. But underneath, there were kids who would wear Dior Homme by Hedi Slimane—it was rare because it was early on in 2002. I didn’t even know exactly what Dior Homme was at the time.” He continues, “The early aughts were a crazy period in Brooklyn and I was just absorbing what was around me.”

Outside of powerhouses McQueen and Gaultier in the ’80s, further influences for Oliver appear to be homegrown. “I started to go out and I was hanging out with the homothug kids. That culture was about taking street clothes to another level, but allowing them to still remain street clothes.” Ah, homothug, a word one doesn’t hear often in 2013. As with many subcultures it can be hard to pin down its collapse. “It’s crazy right? I don’t know \[when it happened\] but it just vanished. Maybe the failing economy was part of its demise, too. But ‘homothug’ was losing its identity because so many kids wanted to imitate it \[that\] it wasn’t authentic anymore. It was very clique-y toward the end. When the kids who originate the look know it’s over, then you know it’s done.”

Oliver’s first offerings in 2006 were light in construction. “I started to do slogan T-shirts. I didn’t really start with a brand or anything—I was just printing things and experimenting with T-shirts and sweatshirts, then moving on to more clothing items.” That began to change for the designer in 2007. “I started to experiment with cutting and sewing. I would take a sweatshirt and reconfigure it and then I start to think about doing it from scratch, like making patterns for them. The first ‘collection’ so to speak, was around mid-2008.”

That fall collection, ‘Higher Learning,’ contained black sweatshirts with cutout inside sleeves, a black and gray windbreaker with black knee shorts, a black knee tee-dress with white prints, and black shorts with black tights and slim sweat tops. There were black fluid embroidered dress shirts and white “Realness” logo tee-dresses worn with nylon cropped coats. In this—his first “real” season—the parameters that would define the designer’s aesthetic began to emerge.

From there, with the help of a production partner, Oliver began to explore more complex techniques, experimenting with pleating and zippers until 2009, when his collections abruptly stopped. “My production manager was leaving the country and I wasn’t able to complete the new collection. At the time I was DJing at events with Venus X \[of GHE20G0TH1K\] to help finance the collection, so I had to stop until mid-2011.” The break may have become a necessary gap in the designer’s creative process. “I took the time that I was doing DJ gigs to think about how to reconfigure things, how it all works together, and how to reemerge.”

His comeback in 2011 came after that two-year hiatus, when the designer was able to scrape together funds for a presentation. “It wasn’t a collection, I was just putting a lot of different concepts out there—nothing cohesive just a bunch of ideas. I wanted to come back with different elements that would be coming soon.”

The show was a varied offering: gray tight sweatpants with a front skirt panel and long back train; a gray wool jacket with suspenders serving as button closures, paired with white cotton asymmetric shorts with one flared leg. A mixed cast of models wore re-appropriated UFO pants with tight doo-rags on their heads, walking around the small loft in white or black thigh high socks and old Jack Purcells modified into slippers. That evening’s gathering downtown was a quiet explosion far from fashion’s mainstream. From there, HBA began to regain its foothold within popular culture. Most recently, rapper A$AP Rocky closed the Fall 2013 show, prowling down the runway in a charcoal neoprene slim logo coat and black capri pants, cementing HBA’s current status among diverse urban performers and audiences.

His current production expansion is quiet and gradual with each move carefully considered. He notes that his pace is intentional, as he proceeds with HBA’s resurrection “slowly and in an organic way.” His pieces are currently available at Opening Ceremony and VFiles in New York, Colette in Paris, online retailers like RSVP Gallery, Selfridges, and Harvey Nichols in London. Not bad for a designer peddling wares that can be a bit tougher to swallow than your average high street knock-offs. Oliver is quick to remind us, “There are kids who want to present themselves just a little bit ‘off’ from the mainstream street look.” Oliver is one of those kids, and as the originator of his own subculture, it appears he has its identity confidently in check.

_Photographer_: Aram Bedrossian for Factorydowntown.com, New York. _Associate Fashion Editor_: ZaQuan Champ. _Models_: Manny Cruz, Eric Ramos, and Taejahn Taylor for Requestmodels.com, New York.

Grooming Notes: Repairing Moisturizer Emulsion by Dior Homme and Pure Abundance Volumizing Hair Spray by Aveda.

%20E%CC%81coute%20Che%CC%81rie.jpg)

.webp)